BatChrist: Born (and Re-Born) in Hell

Depending on how you choose to count, there are either three or four Batman resurrections in The Dark Knight Rises.

Depending on how you choose to count, there are either three or four Batman resurrections in The Dark Knight Rises.

Depending on how you choose to count, there are either three or four Batman resurrections in The Dark Knight Rises.

Depending on how you choose to count, there are either three or four Batman resurrections in The Dark Knight Rises.

Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight Rises is an incredibly ballsy movie. I don’t mean its scope and ambition, both of which are indeed impressive. I mean the audacity of choices that could have easily backfired: following Heath Ledger’s nuanced, razor-sharp Joker with the nearly blank thug Bane; recycling Batman Begins’ sinister plot, doomsday machine, and League of Shadows; inserting teenage-boy masturbation fantasy Catwoman into a universe largely devoid of sex appeal and camp (and non-Rachel Dawes women, period); crafting a lengthy, convoluted first act made even less comprehensible because of the sound design and score; and relegating Batman to captivity of one sort or another for the vast majority of the movie’s first 115 minutes.

Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight Rises is an incredibly ballsy movie. I don’t mean its scope and ambition, both of which are indeed impressive. I mean the audacity of choices that could have easily backfired: following Heath Ledger’s nuanced, razor-sharp Joker with the nearly blank thug Bane; recycling Batman Begins’ sinister plot, doomsday machine, and League of Shadows; inserting teenage-boy masturbation fantasy Catwoman into a universe largely devoid of sex appeal and camp (and non-Rachel Dawes women, period); crafting a lengthy, convoluted first act made even less comprehensible because of the sound design and score; and relegating Batman to captivity of one sort or another for the vast majority of the movie’s first 115 minutes.

How about a magic trick? I shall transform Christopher Nolan’s 144-minute The Dark Knight into a significantly better movie by trimming eight minutes from it.

How about a magic trick? I shall transform Christopher Nolan’s 144-minute The Dark Knight into a significantly better movie by trimming eight minutes from it.

In my hastily keyboarded notes after seeing Inception last weekend, I spent much time faulting Jim Emerson for his dismissal of Christopher Nolan and of the movie. Emerson made sweeping, unsupported generalizations in the service of his obvious dislike of Nolan’s movies. His pieces (and his responses in the comments sections) represented an attack rather than an argument. It’s only fair, then, to praise Emerson for his essay yesterday, which restates his problems with the film but does so much more cogently and generously.

In my hastily keyboarded notes after seeing Inception last weekend, I spent much time faulting Jim Emerson for his dismissal of Christopher Nolan and of the movie. Emerson made sweeping, unsupported generalizations in the service of his obvious dislike of Nolan’s movies. His pieces (and his responses in the comments sections) represented an attack rather than an argument. It’s only fair, then, to praise Emerson for his essay yesterday, which restates his problems with the film but does so much more cogently and generously.

In at least four of Christopher Nolan’s seven feature films, the plots and/or fixations are initiated or propelled by the death of a man’s spouse or girlfriend. Considering that Nolan’s primary thematic interest is obsession, isn’t this a little strange? The realization struck me the day I saw Inception, in which everything Cobb does involves “being with” his dead wife Mal or being reunited with his kids, from whom he’s separated because of how Mal died.

In taking down Christopher Nolan’s Inception, Jim Emerson writes: “[W]hat this movie’s facilely conceived CGI environments have to do with dreaming, as human beings experience dreams, I don’t know. … [T]he movie’s concept of dreams as architectural labyrinths – stable and persistent science-fiction action-movie sets that can be blown up with explosives or shaken with earthquake-like tremors, but that are firmly resistant to shifting or morphing into anything else – is mystifying to me.” The complaint is fair enough, given that Inception regularly refers to “dreams.” But what’s going on is only marginally related to how “human beings experience dreams.” The movie’s plot concerns espionage that uses as its tool a shared, drug-induced dream-like state with environments created by external “architects.” And if one does a little thinking, one realizes that the technique of the premise is effective only if scientists and practitioners can exercise control over the dreaming – that is, if they eliminate the inherent fluidity, randomness, and chaos.

In taking down Christopher Nolan’s Inception, Jim Emerson writes: “[W]hat this movie’s facilely conceived CGI environments have to do with dreaming, as human beings experience dreams, I don’t know. … [T]he movie’s concept of dreams as architectural labyrinths – stable and persistent science-fiction action-movie sets that can be blown up with explosives or shaken with earthquake-like tremors, but that are firmly resistant to shifting or morphing into anything else – is mystifying to me.” The complaint is fair enough, given that Inception regularly refers to “dreams.” But what’s going on is only marginally related to how “human beings experience dreams.” The movie’s plot concerns espionage that uses as its tool a shared, drug-induced dream-like state with environments created by external “architects.” And if one does a little thinking, one realizes that the technique of the premise is effective only if scientists and practitioners can exercise control over the dreaming – that is, if they eliminate the inherent fluidity, randomness, and chaos.

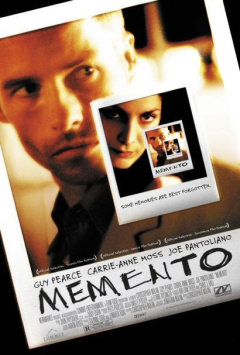

Christopher Nolan directed five movies released this decade; two of them are nearly perfect, one of them has unparalleled rigor for a superhero movie, and the other one has Heath Ledger’s Joker casting an enormous shadow over (and therefore obscuring) its many flaws. The unnecessary remake of Insomnia was the necessary bridge between Memento and Batman Begins – from independent to studio work – but beyond it Nolan has made nothing but winners. To be clear, I don’t believe Nolan is a great filmmaker, and I’m skeptical he’ll ever equal any of these four movies, even though he hasn’t yet turned 40.

Christopher Nolan directed five movies released this decade; two of them are nearly perfect, one of them has unparalleled rigor for a superhero movie, and the other one has Heath Ledger’s Joker casting an enormous shadow over (and therefore obscuring) its many flaws. The unnecessary remake of Insomnia was the necessary bridge between Memento and Batman Begins – from independent to studio work – but beyond it Nolan has made nothing but winners. To be clear, I don’t believe Nolan is a great filmmaker, and I’m skeptical he’ll ever equal any of these four movies, even though he hasn’t yet turned 40.

Memento is such a triumph of tricky narrative structure that it’s difficult to get (and keep) a grip on what happens, let alone the objective truth of its protagonist’s past. Christopher Nolan’s second feature, which he wrote and directed based on his brother Jonathan’s short story, seems perpetually slippery and elusive. I’ve seen it at least six times since it was released in the U.S. in 2001 (it debuted at festivals in September 2000), and even though I know it well, each time it repeatedly throws me off. The movie’s closing line – in context, a sick joke by Nolan – is an excellent summary of how I feel watching it: “Now … where was I?”

Memento is such a triumph of tricky narrative structure that it’s difficult to get (and keep) a grip on what happens, let alone the objective truth of its protagonist’s past. Christopher Nolan’s second feature, which he wrote and directed based on his brother Jonathan’s short story, seems perpetually slippery and elusive. I’ve seen it at least six times since it was released in the U.S. in 2001 (it debuted at festivals in September 2000), and even though I know it well, each time it repeatedly throws me off. The movie’s closing line – in context, a sick joke by Nolan – is an excellent summary of how I feel watching it: “Now … where was I?”

Let’s break this down like a logic puzzle. Iron Man is a better beginning-to-end movie than The Dark Knight or Hancock. The Dark Knight’s best scenes and moments are easily superior to anything in the other two movies. So which did I like best, and find the most affecting? Hancock, of course.

Let’s break this down like a logic puzzle. Iron Man is a better beginning-to-end movie than The Dark Knight or Hancock. The Dark Knight’s best scenes and moments are easily superior to anything in the other two movies. So which did I like best, and find the most affecting? Hancock, of course.

I start an essay for most every movie I see. Whether I actually finish the essay – or even make any headway on a thesis – is another matter entirely. Today I’ll be the old man who runs out of candy at Halloween and starts handing out worthless crap that’s lying around the house.

I start an essay for most every movie I see. Whether I actually finish the essay – or even make any headway on a thesis – is another matter entirely. Today I’ll be the old man who runs out of candy at Halloween and starts handing out worthless crap that’s lying around the house.