Halloween is but a memory, so your opportunity to watch The Haunting of Hill House spoiler-free has passed. I’ll start by reminding you that Nicole Kidman is a ghost. And then I’ll note that this analysis assumes you’ve already seen Hill House.

An Overly Close Reading of The Haunting of Hill House

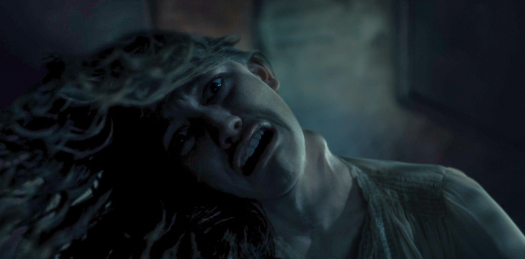

In the third episode of Netflix’s The Haunting of Hill House, the “sensitive” Theodora Crain lays her hand on the forehead of her dead sister Eleanor, and we get, in essence, what we expect. Eventually.

It takes a good 20 seconds to get there, which feels like an eternity, and we aren’t prepared for the physical or emotional violence of the reaction. Both of those components make that passage scary – the dread of waiting, and then Theo’s clear devastation.

Wisely, director and series creator Mike Flanagan and episode writer Liz Phang don’t show what Theo saw. It will be another two hours before viewers experience Nell’s death and its immediate aftermath, which we feel certain were the cause of Theo’s revulsion. And it will take another three episodes before the truth becomes clear in her tearful roadside outpouring to Shirley: that what she experienced in the mortuary was not her youngest sister’s death but a consuming emptiness.

This is but one example of the intricate long game of The Haunting of Hill House. Theo’s eighth-episode confession resolves a mystery from the sixth episode (what was going on with Kevin) as well as that huge question from the third. It also explains the closing seconds of the third episode, the “Don’t touch me!”/“Touch me!” juxtaposition; the normally skin-contact-averse Theo was desperate to feel anything after her sensitivity suddenly disappeared.

The funny thing is that, if we’re paying attention in the third episode, we already have all the information we need to get an accurate sense of what Theo felt with Nell. In fact, she stops just short of telling us: It was the same thing she had experienced with the girl who was being molested by her foster parent – a barrier to cope, a defense mechanism. “This kid, she built up so many emotional walls,” Theo tells her lover. “I touched her hands, and I didn’t even – . She just needed help, and no one was listening. And it’s so much like Nellie.”

Flanagan and Phang obscure this nugget in the large gulf of intensity between Theo’s responses, even though it takes little work infer the source of that gap. Nell is her sister, and she’s dead, and Theo should have been listening but wasn’t.

Revisiting The Haunting of Hill House helped clarify the fundamental dissonance of the show – that running counter to its hopeful, tidy conclusion is something far messier in both its ghost and family stories.

And it was downright startling to recognize how clearly the first four episodes show the myriad ways the Crain children failed their youngest.

The Peril of Peaking in the Middle

It’s easy to overlook that aspect because Hill House operates first and foremost as a skillful haunted-house story – something that can be binged and enjoyed purely on those terms.

I haven’t read Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House, but I’ve watched the Robert Wise/Nelson Gidding 1963 adaptation The Haunting many times. As best I can tell, Flanagan (who wrote or co-wrote four of the episodes) has little interest in the source material beyond appropriating the setting, some names and basic characterizations, the Dudleys, and passages and phrases. (He turns the opening into a little joke. It plays differently when the author ain’t Shirley Jackson.)

In place of the novel’s group of unrelated investigators stands the Crain family: father Hugh, mother Olivia, and five children – Steven, Shirley, Theo, Luke, and Nell. While renovating Hill House one summer, some members of the family … well, you know … and Olivia kills herself.

By the end of the show’s first chapter, Nell has returned to Hill House after more than two decades and died, and Flanagan takes his sweet time getting where everybody knows he must finally go.

For six episodes, it feels potentially transcendent – not only managing the difficult task of long-form horror but doing it with confidence, panache, and richness. And then it seems to fall apart.

That’s unfair because the show is rarely less than compelling, and its low points are limited to parts of three episodes – with one of them, admittedly, being the conclusion. But the impression that it limps to the end illustrates the problem it created for itself by being so strong in the middle.

Hill House has two bravura bits straddling the midpoint of its 10 episodes: the sweetly yearning and then punishingly horrifying closing section of “The Bent-Neck Lady” – which gets even more poisonous as you digest it – and the entirety of “Two Storms.” It’s never more viscerally scary than in the final moments of “The Bent-Neck Lady,” and the sadness of that chapter is rivaled only by the closing seconds of “Two Storms.”

There’s the additional problem that the fifth episode marks the end of Hill House’s smart and well-executed every-child-gets-an-episode approach. “Two Storms” is something else entirely – the series high point in direction, family dynamics, and enormously successful low-key scares, with its numerous long takes on the right side of gimmicky. (There are enough cuts to help it avoid feeling unnatural, and it finally settles into a conventional editing rhythm.)

But how the hell do you follow all that? Had The Haunting of Hill House ended after six episodes, it would have left some nagging questions, but it would have still felt complete and satisfying.

Then there’s the ending itself, which has a defiantly upbeat tone that feels incongruous with the rest of the show – and seems to whistle really loudly past the graveyard.

As a result, I dove in for a second helping of Hill House with weirdly low expectations considering how much I’d enjoyed it. I anticipated that those opening six episodes would feel diminished by the last four.

The first pleasant surprise was that the show’s back end wasn’t nearly as problematic as I remembered.

The second was that in the rush to finish it the first time, I’d missed a lot – especially the slowly developing horror of how carefully Hill House lured Olivia into an emotional trap with only one out.

The third was that the first six episodes played even better on repeat viewing by helping to subtly recast the whole – undermining without negating the tone of Hill House’s final minutes. The faults are still there, but the early episodes carve out room for readings that substantially darken it.

As you might have read, Flanagan filled the show with background ghosts. He also loaded it with clues about how to excavate the horror in his closing’s uplift.

The Bricks (Mostly) Met Neatly

Flanagan’s creepy chops are plainly evident in the opening of the first episode. In the hallway, the camera pushes forward, suggesting a ghostly point of view. It might not fully register that the door Hugh closed was again open – but part of you knows it. Flanagan holds shots too long to be comfortable, and as a result you’re searching the frame, looking for what you expect to be there – which is especially true as you wait … and wait … and wait for the Bent-Neck Lady to show her face, of course cocked at an unnatural angle.

The show gooses viewer alertness in a variety of ways – even if you don’t recognize that Flanagan has hidden a bunch of spectral Easter eggs. (There’s one in that opening.) Basic exposition comes slowly, to the point that my wife and I were confused about the number of Crain children in the first episode. There are 13 main actors playing seven Crain roles in two primary periods (their early-1990s time at Hill House and the present), plus numerous flashes to events in different times – and the show is coy enough about the past (“Hill House: Then”) that it’s almost a game to place it precisely. Adult Shirley and Theo are similar enough in face, hair, and build that one has to work initially to keep them straight.

There’s an undeniable kick in watching Flanagan toy with the audience. It wasn’t apparent to me until the third episode that he was giving each child a chapter in the story. We start with Steven, a paranormal skeptic who has nonetheless parlayed his family’s Hill House experience into a career as a hack writer about haunted places. Then there’s Shirley, a mortician who shares her father’s almost compulsive need to “fix” things beyond fixing. Theo, a child psychologist with physical-intimacy issues. Luke, an addict. And finally his twin sister Nell, terrorized by the Bent-Neck Lady at Hill House and beyond, and then widowed after a mere eight months of marriage.

Flanagan’s chosen structure allows him to judiciously sketch both past and present, using character experience to convey information while hiding key bits because of character ignorance. He leans heavily on Lost’s too-neat storytelling style – important flashbacks triggered by the present – but he mostly does it with playful elegance. You can almost see a smile as he tells his story in circles while the audience desperately wants it to move forward.

And it’s a throwaway touch, but each early episode’s focus on a single character is violated with clear forethought. That was to be expected in Steven’s, and we should be grateful that Flanagan made no attempt to introduce his characters and cast only in interactions with the eldest child. But it’s also true in Shirley’s, Theo’s, and Luke’s episodes – in which we break away from the central character precisely once. In Nell’s episode, it happens at least once (when she buys heroin for Luke, but we stay in the car with him) and arguably two other times (when Steven and Shirley decline her calls). This is Flanagan giving himself an escape route for later chapters; when the format is trashed in “Two Storms,” he can accurately note that no consistent rules were ever established.

There’s something else going on in the early episodes that I only saw much later: Flanagan deals with the children in descending order of age, and from least- to most-haunted, building anticipation.

This relegates Luke and Nell to the sidelines until the fourth and fifth episodes, respectively. After three hours, we have a pretty thorough understanding of Steven, Shirley, and Theo – the three children who’ve made places for themselves in the world – but only impressions of the troubled twins. Adult Luke doesn’t even merit a proper introduction in the opening episode until he’s shown stealing from Steven; his first appearance comes in the sequence showing the Crains bolting up in bed, gasping for air, at the moment of Nell’s death. And their baby sister is little more than a bit player in her own tragedy for Hill House’s first four episodes. The effect is to illustrate how marginal Luke and Nell are in the lives of their self-involved siblings.

Luke and Nell don’t see it, though. As a way to calm himself, Luke as a child creates a trick in which he counts objects while touching them all – “One, two, three, four, five, six, seven,” an incantation invoking the protective power of their seven-member family. He teaches it to Nell, and we see them both use it as adults. Yet it’s a wish – an ideal of family, and of their family – that reality doesn’t support.

Still, Luke and Nell are supposed to have each other – the “twin thing” – but it’s a one-sided relationship. We see Luke’s best self in his episode – showing his ability, when clean, to be a support system at personal cost. And then we see his worst self in Nell’s showcase, pressuring her into buying him drugs when she’s driving him to rehab. He manipulates her, telling her how he always believed her and asking her to believe in him, explaining his request at the expense of what she wants to say. Despite her psychic bond with Luke, Nell is genuinely alone in her family.

She just needed help, and no one was listening.

What Do You Want?

In “The Bent-Neck Lady,” Nell drops a number of crucial lines.

To her sleep tech and future husband Arthur: “It’s nice to be listened to.”

To Steven: “You’re supposed to protect me.”

And to Steven again: “I don’t ask you for anything. Ever.”

These ideas pop up again and again in Hill House. The eldest three Crain children have never given Nell and her problems enough time, patience, or empathy. In the present, Luke has devoured all the attention, resources, and chances that might have helped Nell, aided in large part by her unwillingness and inability to grab the spotlight and ask for help.

It’s no accident that neither Steven nor Shirley accepts Nell’s call in the first episode; they’ll deal with her when it’s convenient.

But when Nell shows up in Steven’s apartment, he can’t blow her off. Exasperated, he says: “Fine. You’ve got us all listening. What do you want? What’s so damn important, Nell?”

By this point, of course, Nell is dead. We will later see her ghost utter a series of horrified “no”s to herself as she finally understands her fate. We will see her say words to Luke: “Go” and “Don’t.” But when she’s asked the question directly – “What do you want?” – she’s clearly trying to get something out and can only scream.

This is the child who always asked Santa for gifts for her brothers and sisters, but not for herself. This is the child who wrote letters to her father, telling of her brothers and sisters, but not herself. This is the child who, having a pretty good sense of what awaited her at Hill House, only expressed concern for Luke.

It’s Yours Now

When Nell returns to Hill House, she’s obviously terrified: “It’s just a carcass in the woods,” she says to herself. But it lights up warmly, and the porch light blinks twice – her mother’s signal to return home.

For nine or so minutes, the house gives her everything she wants. Her mother is there, helping her get dressed for her marriage to Arthur – unlike in real life. Luke attends the wedding – unlike in real life. Nell dances with Arthur. And then, finally, from high above the ground floor, Olivia gives her the long-promised locket – a symbol of family, and a reminder of her connection to Luke – and fastens its chain around her neck. “It’s yours now,” she says.

The greatest horror is not the thing that surprises us but the thing we see coming from miles away that nothing can stop.

“Mom?”

“It’s okay, honey.”

Of course, the necklace is suddenly a noose – underscoring the idea of family as an instrument of harm rather than help.

“Mommy?”

“It’s time to wake up, sweetheart.”

Of course, Olivia gives Nell a little push.

Of course, the fall breaks Nell’s neck.

And of course, she drops again, and again, and again, and again (“No no no no no no … ”), and again (that big fucking shriek).

I’ve watched this section a whole bunch of times – usually in isolation – and it has never failed to crush me. Some of that is the inevitability, and a big part is the expert execution – shot selection, editing, performance, and agonizing pauses mixed with things happening way too quickly.

More than anything, though, it’s how this passage locks Nell in an infinite loop of fear and pain. This is the literally inescapable tragedy of The Haunting of Hill House: From her family’s first night in that place until her hanging, Nell is simultaneously alive and dead – and doomed to repeat the circle forever. Worst of all, as the Bent-Neck Lady she begins to understand this as she falls, and there’s only one thing to do with that realization: scream.

Nobody Could See Me

“Two Storms” is basically Hill House’s reset button. It smashes the established format with glee while approaching its familial theme so very literally: that the surviving Crains can’t see a Nell in plain sight, whether a corpse or a ghost.

The episode’s formal brilliance is that it is intensely theatrical while also being intensely cinematic. Its long takes and sorta confined nature give the impression of a play, with the added benefit that it could nearly stand alone from the remainder of the series. (I love that the episode gives just enough information that each character and the family dynamics are vivid without the benefit of the previous episodes, such as Steven’s “Still not a hugger, eh?” comment to Theo.) But of course a play wouldn’t allow for all the business that happens when the camera’s looking somewhere else – the appearances of the Bent-Neck Lady, children taking the place of adults, the buttons.

Plot-wise, nothing that happens in “Two Storms” matters much. The Crains manage, barely, to remember Nell’s life with a few touching stories, but they’re mostly busy drinking and lashing out at each other, reopening old wounds that we’re already aware of. The flashback to Hill House is largely a collection of isolated curiosities – Nell seemingly disappearing, Olivia seeing some ghosts and impossibly hopping from place to place, and the house itself apparently trying to implode.

It gives the audience a chance to breathe, and to let Nell’s demise – especially her experience of it – settle. But we aren’t allowed to forget the defining feature of her story.

Steven: “I won’t let anything happen to her. To any of you guys. That’s my whole job – first thing they teach us in big-brother school.”

Luke: “I’ll never let you go again. Never again. I promise.”

Nell: “I was right here. I was right here the whole time. None of you could see me. Nobody could see me.”

And the Bent-Neck Lady stands – alone and silent – next to her casket.

The episode – otherwise mostly rehash and incidental stuff – exists primarily to lead us into this moment, intensely creepy and deeply sad at the same time.

Yet right in front of us is something important and new that’s easy to miss. Without any doubt, the spectral Nell now exists in two distinct forms.

The first, as I’ve already noted, is the endless circle: Nell lives her life, is hanged, and haunts her younger self, who lives her life, is hanged, and on and on. This is horrific enough, and it’s amplified by a few realizations: Living Nell and dead Nell share moments, throwing into question both the idea of linear time and our strong belief that individuals have a single consciousness.

“Two Storms” shows her ghost beyond that – both temporally and geographically. She is in the funeral home, and clearly independent of any other character’s point of view.

Of course, Steven also saw dead Nell outside of her loop of hell, but that could potentially be written off as some hallucination reflecting a spiritual family bond. In “Two Storms,” there’s simply no way to explain away the two ghosts of Nell.

You’re welcome to complain about this in a clickbait article (“The One Huge Mistake in The Haunting of Hill House That Everybody Misses”), but I think the show is too carefully crafted to support the reading of a narrative cheat or error.

As for evidence that this is an intentional fracturing of the afterlife, look no further than the first episode’s recitation from Hamlet: “There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, / Than are dreamt of in your philosophy.”

In other words, our neat conceptions of the afterlife and ghosts and souls might simply reflect our inability or refusal to think about them in ways that are more troubling.

Crucially, the show’s ending is entirely dependent on this premise firmly established in “Two Storms,” that hauntings – and individual ghosts – can contain multitudes and are bound by neither time nor space. That’s plainest with Nell, but it’s reinforced by the strangeness we see from that night at Hill House.

On Vasectomies and Boob Punches

Once “Two Storms” brings Nell’s story to a close, there are still plenty of questions on the table. In rough descending order of import and likely audience interest: How did Olivia die? What is Hugh hiding from his children about That Night? Is Hill House malevolent, or is it merely haunted, pushing unwell people over the edge? What’s behind that ever-locked red door? Why do the Dudleys persist in clogging up the story, except as a nod to Jackson’s novel? Will Luke relapse? Who is the guy raising his glass to Shirley in episode two? What’s up with elder Hugh talking to himself? Is Theo lesbian or bisexual? What’s the source of Steven’s marital troubles? And could things really get so bad between Shirley and Theo that one would boob-punch the other?

Some mysteries, as This is Spinal Tap taught us, are best left unsolved, but the back end of Hill House missed that lesson.

For the last time (I swear), the return to relative narrative normalcy after the emotional wringers of “The Bent-Neck Lady” and “Two Storms” would be a letdown under nearly any circumstances. But Flanagan and his collaborators make quite a few miscalculations that exacerbate it.

Hugh – at long last – gets his focus episode in “Eulogy,” and it has plenty of strong moments. But it ends on a howler – Bad Ghost Olivia has destroyed the Forever House model! – that foreshadows the general incompetence of “Witness Marks.”

That eighth episode is the killing-time chapter I hoped Hill House could avoid. Some pieces get shifted, but the story moves barely at all. The absence, for the first time, of a structural or filmmaking conceit highlights bad narrative choices. An inordinate amount of time is spent building to the startling revelation of Steven’s vasectomy, which wrongly infers that anybody needed or wanted more Steven drama or a fuller picture of his separation from Leigh. (The show will later make a similar mistake with Shirley, and in both cases it’s compensation for a nonexistent shortcoming in characterization.) And, yes, things get bad enough between the surviving sisters that Shirley punches Theo in the boob.

Yet for all its problems, “Witness Marks” ends incredibly strongly. After Hugh finally spills some beans about Hill House, we get the series’ best jump scare, followed immediately by a wrenching monologue from Theo, with the fickleness of her sensitivity standing as a sharp metaphor for the stages of grief. And then we see, finally, Hill House as an active force hell-bent on its own survival.

Fresh Hells

Even as Flanagan and company pause the present in Olivia’s “Screaming Meemies,” Hill House begins to assemble its pieces into something hinting at the finished picture. In just the first 10 minutes, there’s the old-timey clock repairman. Olivia sipping tea, and immediately being struck with a migraine. More arguments about Luke’s friend. A repetition of Shakespeare. Confusion about Olivia’s reading room. Another horrifying disruption of space and time that hints at Luke’s future peril and reminds us, again, how difficult it is for Nell to communicate, in life or in death. (To simply utter the word “Mommy,” she must first cut the wire holding her mouth shut.)

Some of these details echo backward, but most gain meaning from what we will soon learn. Given the stasis of the previous three episodes, this relative torrent signals the sprint to the finish line.

The anxiety, dread, and frights here mimic core features of “The Bent-Neck Lady.” But because of “The Bent-Neck Lady” – and because Nell’s and Olivia’s stories basically end the same – those things alone would be insufficient. So Flanagan finds a new horror.

As the moment approaches, you probably see it coming, but you probably should have seen it sooner. Sooner in “Screaming Meemies,” certainly, but sooner in the series as a whole. All the discussion of tea parties. Hugh’s curiously adamant refusal to talk about That Night – to his family and the police – even though everybody knows Olivia killed herself. Puzzled reactions meeting talk of treehouses and game rooms. Olivia with a screwdriver to Hugh’s throat. The bottle of rat poison.

It’s one thing to harm oneself. It’s quite another to willfully harm somebody else. Well into its ninth episode, the physical damage of The Haunting of Hill House has been limited to suicide – or some ghost-assisted version of it.

This is how to compete with the Bent-Neck Lady, and it unfolds in what feels like slow motion. The ghost of Poppy Hill whispers, and Olivia becomes convinced that her life is a dream from which she needs to wake – a way to end the pain. She has seen what lies ahead for Luke and Nell, her babies, and she can save them, too, if she wakes them up.

So in the room with the red door there’s a tea party, and rat poison, … and an unexpected guest that you should have expected.

The Dudleys and Abigail have long felt like strangely inert narrative elements. But in a machine as gorgeously designed as Hill House, we should have instead recognized them as dormant, waiting to be activated. Pay attention to Mr. Dudley’s story in Hugh’s episode, when he talks about his “first” child, stillborn. We know the Dudleys live in the woods on the edge of the Hill House property. We have seen Abigail.

In “Screaming Meemies,” we get direct mention, for the first time, of a living Dudley daughter. And Luke tells us (no no no no no) that Abigail lives in the woods.

This is how to match the Bent-Neck Lady.

“She lies,” the old woman says to Olivia about Poppy, too late.

And this is how to eclipse the Bent-Neck Lady. If this is a dream, you must wake up. If this is reality, you can’t face it. You’re no longer sure which is which, but it doesn’t matter. Either way, you’re looking down at a welcoming landing spot far below.

Rescues, Reunions, and Reconciliations

From these depths, Flanagan has to give the audience a way out of the misery. Yes, it’s horror, but it’s 10 hours of horror, and a conclusion that couldn’t offer at least some light would be cruel.

For the first hour of the concluding chapter, it looks like he’ll pull it off. There’s a clever bit of misdirection as Steven seems to be revisiting his most-famous book at some point in the future. Leigh is pregnant, and Luke and Hugh died at Hill House.

But she quickly turns from supportive spouse to unflinching judge, memorably poking Steven with uncomfortable truths and comparing his writing process to shitting. As she darkens into something very familiar, Nell calls Steven’s name and touches him.

Back in reality and in the present, the surviving Crains are all at Hill House, and each of the children is under its spell, living in fantasies that turn into nightmares while the room with the red door consumes them. Only Luke’s bright tea-party reunion resonates among these, but it’s a sharp enough idea to survive Shirley’s man with the drink.

And it’s downright thrilling in the best way to have each child rescued by the voice and touch of the selfless and nearly whole Nell – who does not share her mother’s confusion about what it means to wake up. And then to watch Nell finally finding her voice, her incoherent, circular ramblings starting to make sense. And then to have her forgive each of her siblings in turn, and then to disappear.

But the red door is still locked. Outside that room, Olivia intervenes to stop Poppy’s attempted seduction of Hugh, and we have this hope that, like Nell, she is seizing her opportunity to save her family. “Journeys end in lovers meeting,” the wife says to her husband, quoting Jackson’s book.

It soon becomes clear to Hugh, though, that this Olivia is not the woman to whom he was married but the ghost who has been aching for her family in Hill House for 26 years – and she’s not about to let them go now. At first he engages her on her terms – arguing with love, as he might say – but he finally offers a deal.

The man whose “I can fix this” mantra rang ever hollow has, indeed, fixed this. The kids are released, and Theo and Shirley depart for the hospital with Luke.

Steven then sees the remainder of That Night, as the Dudleys discover their dead daughter, and plead with Hugh to leave Hill House as it is. “This house, it’s full of precious, precious things,” Mr. Dudley says, “and they don’t all belong to you.” A handshake.

In full savior mode, Hugh says to Steven: “Take care of each other. And be kind to each other. If nothing else, be kind.”

Hugh, Olivia, and Nell embrace, Olivia’s eyes meet Steven’s – her expression ambivalent – and the red door slowly closes.

As Steven prepares to leave, ghosts assemble around him, and his eyes dart around, but he’s doing everything in his power not to see them. He opens the front doors of Hill House and walks out.

There are two great potential endings here. As much as cutting things off after “Two Storms” would have resulted in a uniformly excellent whole, I’m happy to accept the lows of “Witness Marks” to finish with either of these moments, less than 50 seconds apart.

Alas, there’s an epilogue, and Flanagan lays it on thick, and pushes the sentiment and resolution buttons even harder than he already had. Steven with Leigh, Shirley with Kevin, Theo with Trish, Steven with Leigh again, and finally Luke on the two-year anniversary of his sobriety, with all of the aforementioned present. There’s a song, and that’s topped by the voice-over that makes one wince in fear of where it’s going, and that’s precisely where it goes, with exactly the wrong word choice.

Because I’m happy with the relatively cheery ending of a ghostly family reunion of Hugh, Olivia, and Nell, I can’t really complain about the content of the actual closing. The issue is the extent to which we’re forced to endure it. We have enough information – and enough instruction from Hugh, and enough evidence that Steven has listened – that we can infer a happy-ish ending to the stories of the surviving children without seeing the seeds of reconciliation and the cake.

So the idea of the ending works well enough, and has – like the show’s ever-repeating piano theme – a simple but nuanced bittersweetness. In death, families can be reunited at Hill House. The living can’t bring back the dead, but they can control how they treat others.

Be kind to each other. If nothing else, be kind.

A Better Picture

But 4,000 words ago, I made a claim as my thesis – that the first six episodes of Hill House “carve out room for readings that substantially darken it.” To that I’ll add that the face-value ending and darker interpretations of it are not, as Steven would tell us, mutually exclusive.

As I’ve already discussed, a big part of the darkness is Nell’s tragedy – that she needed help, that she didn’t know how to ask for it, and that her family never gave it. This cannot be erased, even if she has absolved each of her siblings.

The audience would be wise, however, to look at the ending of Hill House – and particularly the warmth of its tone – skeptically. It absolutely should not be dismissed, but it shouldn’t be trusted, either.

(It’s worth noting that Flanagan has said he toyed with but opted against a visual clue to flip his ending’s meaning. Then again, maybe you should be skeptical about that, too.)

If you’ve made it this far, you’ve suffered a lot of my blathering, so I’ll try to be brief.

One: The Haunting of Hill House has shown clearly that an individual’s ghost can take multiple forms and be split into separate consciousnesses. Part of Nell is caught in the Bent-Neck Lady loop, but other parts of her exist outside of it – the one that cannot communicate except in screams and single words, the deeply alone iteration that stands mutely, and finally the spirit who frees her siblings. “I’m scattered into so many pieces,” that version says. The same is true of Olivia, whom we’ve seen as a ghoul and as something resembling her living self.

Two: Hill House offers no evidence that ghosts can be released or “saved.” For the simple reason of narrative integrity, the Bent-Neck Lady loop must persist even as Hugh, Olivia, and Nell hug. The best we can hope for under these circumstances is that part of Nell and part of Olivia have found a measure of peace with Hugh.

Three: “The thing about an open casket, and I know it sounds scary,” Shirley says in the second episode, “is that it’s a great chance to take all those pictures in your head … and cover it all up with a better picture.” What Flanagan does with his ending is akin to what Shirley does with a corpse: He’s putting a grim reality in the best possible light.

Four: In a really clever final touch, he does this not as the author, but through an author. Based on the series’ opening and closing voiceovers, we understand the narrative (especially at the terminals) as a story Steven is telling.

Five: Once Shirley and Theo leave to take Luke to the hospital in the final episode, what we see is entirely from Steven’s perspective, something no other surviving member of the family experienced or can deny. “I’ll need to take some liberties,” he says in the opening episode. “I always do.”

Six: This might be a second book on Hill House, one that’s less about a haunted house and its ghosts than about people. Maybe it’s something he keeps to himself, a reminder. Most likely it’s a tale he shares with future generations of Crains, a way to tell them about his parents and Nell and 1992 and 2018.

Seven: “The mind,” Steven says in the first chapter, “it is a powerful thing, ma’am. Especially the grieving mind. … A ghost can be a lot of things. A memory, a daydream, a secret. Grief, anger, guilt. But in my experience, most times they’re just what we want to see. … Most times, a ghost is a wish.”

All of that is also true of ghost stories, and especially this one. It is a powerful thing, filled with memories, daydreams, and secrets. Grief, anger, and guilt. It is scary, but don’t worry: Everything will – no, must – be all right in the end.

If liberties have been taken, it’s for a simple and noble reason. This ghost story is, above all else, a wish.

Oh, and one last thing: