(This piece starts with the Apostles’ Creed. You’re advised to start with the Spoiler’s Creed.)

“I believe in … Jesus Christ, his only Son, our Lord, who … was crucified, died, and was buried; he descended into Hell; on the third day he rose again from the dead; he ascended into heaven … .” – The Apostles’ Creed

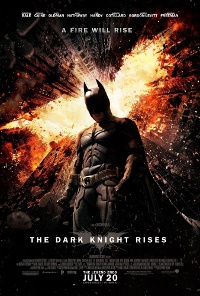

Depending on how you choose to count, there are either three or four Batman resurrections in The Dark Knight Rises.

Depending on how you choose to count, there are either three or four Batman resurrections in The Dark Knight Rises.

First is his return after an eight-year hiatus – which in functional and public terms represented his death. Third (or third and fourth) are the separate resurrections of Bruce Wayne (the man) and Batman (the symbol, in the form of John Blake) after their apparent demises.

In between is the most physical and literal treatment of the idea, with Batman (nearly) killed, imprisoned and (psychologically) tortured in a below-ground Hell, and finally rising to save Gotham.

Superheroes – and especially Superman – have long been seen as Christ figures, and from its title to its returns from the “dead,” The Dark Knight Rises appears to impose that connection on Batman. Aside from the obvious savior similarity, the comparison is knotty – but worth exploring.

Remember that there’s never a point-for-point match between Christ and Christ figures; creators invoke aspects of the New Testament story that (consciously or not) interest or speak to them. Christopher Nolan and his co-writers aren’t mirroring Jesus’ story so much as smashing and reassembling it: stripping Christian ethos out of the narrative and leaving elemental expressions of ego and power and a fundamental battle not between good and evil but between salvation and death.

Let’s start with the problems. Batman is in no way a pure figure. Rather than being sent down from the heavens, he was (figuratively) born at the bottom of a well – the underworld – in Batman Begins.

Let’s start with the problems. Batman is in no way a pure figure. Rather than being sent down from the heavens, he was (figuratively) born at the bottom of a well – the underworld – in Batman Begins.  He can be said to have horns. So the parallels are rough, and Batman might more closely resemble some other “dying god” (a regular motif in mythology).

He can be said to have horns. So the parallels are rough, and Batman might more closely resemble some other “dying god” (a regular motif in mythology).

But like the Jesus of The Last Temptation of Christ, the Dark Knight is full of internal conflict between his mortal, human self (Bruce Wayne) and his immortal, symbolic role (Batman). Alfred tempts him early in Rises, suggesting that by keeping Batman (his sacred duty and true identity) in retirement permanently, he could create a life for Bruce Wayne (his earthly shell and mask) – just as Jesus on the cross dreamed of a simple life as husband and father, the rest of the world be damned.

What Rises and its protagonist do, then, is create a third option. In the process of saving Gotham from a nuclear blast and finally “killing” Bruce Wayne’s Batman, the two halves are separated and given new, divergent lives. (If the movie’s carefully telegraphed ending seems a cheat, it might be because it feels wrong to you that Jesus – I mean Batman – can have it both ways, particularly given the series’ penchant for binary, polar choices.)

While I’m not going to claim that Nolan and his collaborators set out to equate Batman to Christ, the movies from the start have encouraged such readings. In his three Dark Knight movies – where “justice” is at the least an ass-kicking and often death – the Christ figure is in eternal struggle with his Father.

I began my 2005 essay on Batman Begins with an epigraph from Genesis: “And God saw that the wickedness of man was great in the earth, and that every imagination of the thoughts of his heart was only evil continually. … And the Lord said, I will destroy man whom I have created from the face of the earth.” And I explicitly connected the League of Shadows to the Old Testament God, noting that Ra’s al Ghul’s plan “recalls Yahweh’s destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah and, earlier, humanity except for Noah.” Both God and the League of Shadows judge us collectively.

Contrast this with Batman’s idea of justice, which while similarly harsh is individual and – in its formative stages at least – included the word “compassion.” The wicked – and, in theory, only the wicked – are punished, the flip side to the righteous being promised salvation in the New Testament.

In other words, these Batman movies exploit a tension similar to that between the Old and New Testaments of the Christian Bible – vengeance versus kindness.

If Batman is the (relatively) kind Christ in this reading, his spiritual father is Ra’s al Ghul, whose fortress not coincidentally sat on a mountain. (In a sense, Batman was then born both in Heaven and Hell, and if you prefer to see Batman more as a demon than akin to Jesus, recall that Lucifer himself is, in one aspect, a Christ figure: Both were cast from above to the Earth by the Creator.)

The parent-child relationships here are defined by rejection. The God-figure teacher rejects the pupil’s refusal to kill, and Bruce Wayne (mostly) rejects the philanthropic philosophy of his biological father as ineffectual – too kind, with no accountability.

In The Dark Knight Rises, Talia al Ghul was also born in Hell – and in two instances abandoned by that same (and, in this case, literal) Father – while Bane was forged there (the goodness pummeled out of him) and then rejected by God. Yet they, like Job and Christ, persevere in the Father’s work, even though they perceive that He had forsaken them.

In The Dark Knight Rises, Talia al Ghul was also born in Hell – and in two instances abandoned by that same (and, in this case, literal) Father – while Bane was forged there (the goodness pummeled out of him) and then rejected by God. Yet they, like Job and Christ, persevere in the Father’s work, even though they perceive that He had forsaken them.

Batman, of course, spurns that mission, and there’s a moment in Batman Begins when my reading takes on a startling resonance, as the crooked cop claims to know nothing, “swear to God.” We might call that a very poor choice of words, as Batman is none too fond of God: “Swear to me!”

And (speaking of the Joker), while the Christ figure is most clearly manifested in the first and third movies, some biblical allusions can be found in The Dark Knight. Two-Face, as duality made literal, is himself a fallen angel. You might, in the way Gotham finally turns against its savior and casts him out, hear echoes of Peter’s denial of Jesus.

And recognizing that the chief adversaries in Begins and Rises are Father figures, it’s not hard to see the Joker as one, too. Like God, he just exists – no backstory offered or needed – and his schemes are designed to test the moral mettle of both Batman and Gotham, as the Lord tested Job.