Hendrix’s “Machine Gun,” 40 Years After His Death

“Happy New Year, first of all,” Jimi Hendrix says to the Fillmore East crowd at the dawn of 1970. “We hope you have about a million or two million more of them – if we can get over this summer.” He pauses and follows that with a “heh heh heh” that suggests a hint of self-loathing.

“Happy New Year, first of all,” Jimi Hendrix says to the Fillmore East crowd at the dawn of 1970. “We hope you have about a million or two million more of them – if we can get over this summer.” He pauses and follows that with a “heh heh heh” that suggests a hint of self-loathing.

In hindsight, it might be the saddest recorded laugh in history, as Hendrix didn’t survive the summer, dying at age 27 on September 18.

Of course, it would be stupid to read anything into Hendrix’s audience banter beyond the irony of his imminent passing. He was simply acknowledging the lameness of his quip, and he moves on, dedicating the next song to urban warriors and quickly appending: “Oh yes, and all the soldiers fighting in Vietnam.”

And then: “We’d like to do a thing called ‘Machine Gun.'”

The next 12 minutes – captured on the Band of Gypsys [sic] album – almost certainly represent Hendrix’s finest live performance. And it’s not merely the guitar-playing; this “Machine Gun” is the pinnacle of rock musicianship, with the instruments indivisible from the song, its subject matter, and its pitched emotions.

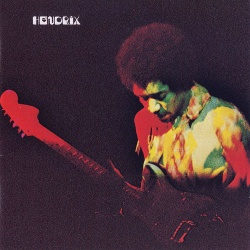

Band of Gypsys was the only non-Jimi Hendrix Experience album released in his lifetime, and its primary purpose was to fulfill a contract – never a good sign. Yet the record – with drummer/singer/songwriter Buddy Miles and bassist Billy Cox – is notable for being funkier and more soulful than any of Hendrix’s Experience work, leaving behind the pop and psychedelic affectations of his canonical studio records. Still, as strong as the album’s other five songs are – closing with a fantastic accelerating jam on “We Gotta Live Together” – they end up window dressing to the titanic “Machine Gun,” which manages to be both expansive and tight.

If you listen to other versions of the song – and two from the same four-show engagement are available on Live at the Fillmore East – it becomes evident that the Band of Gypsys “Machine Gun” is uniquely transcendent.

Other performances are choppy and disjointed – a quality the Coen brothers exploited in (anachronistically) using one to unsettling effect in A Serious Man. But on Band of Gypsys, the song is fiery, fluid, focused, and (until its closing section) without fat. “Machine Gun” here gives the impression of being rehearsed into this lean, solid form, even though all evidence suggests that it was actually just a very happy accident.

The song’s anchors are rapid-fire blasts of guitar, drums, and bass between and beneath nimble but forceful guitar lines that often mimic the vocals. Three verses precede the first solo, and there’s no chorus. Instrumental sections of the song total almost eight minutes, with the internal solos running four minutes, 40 seconds.

It’s obviously an anti-war song, but in its few words it’s also nuanced. It begins almost as an incredulous lament:

“Machine gun /

Tearin’ my body all apart /

Machine gun /

Tearin’ my body all apart /

Evil man make me kill you /

Evil man make you kill me /

Evil man make me kill you /

Even though we’re only families apart.”

Hendrix as a vocalist never strayed far from adequate for me, but in “Machine Gun” there’s a measured urgency to his singing, and his artlessness serves the song amazingly well, appropriately ambiguous.

That pays off in the third verse, which introduces a vengeful side:

“The same way you shoot me down, baby /

You’ll be goin’ just the same /

Three times the pain /

And your own self to blame.”

The political element of the first verse – the “evil man” behind the conflict – is gone, replaced by an in-the-moment fury. Hendrix and the song submit to the conflict instead of merely railing against it.

And that brings us to the first solo, three and a half minutes of eloquent, mournful, haunted rage. It begins with two piercing cries and then runs a gamut of hot feeling in six-string moans, rants, and screams: hatred, anger, defiance, terror, bloodlust, grief – all executed with a grace and fluency that Hendrix rarely sustained in live performance. The playing is expressive and deeply felt but masterfully controlled – the discipline likely a reaction to criticism of his outré style. It’s a stunning convergence of Hendrix’s compositional, improvisational, and technical skills fueled by emotion while exhibiting unusual restraint.

And that brings us to the first solo, three and a half minutes of eloquent, mournful, haunted rage. It begins with two piercing cries and then runs a gamut of hot feeling in six-string moans, rants, and screams: hatred, anger, defiance, terror, bloodlust, grief – all executed with a grace and fluency that Hendrix rarely sustained in live performance. The playing is expressive and deeply felt but masterfully controlled – the discipline likely a reaction to criticism of his outré style. It’s a stunning convergence of Hendrix’s compositional, improvisational, and technical skills fueled by emotion while exhibiting unusual restraint.

(I can think of only one other instance of guitar-playing that gives me a remotely similar chill, when the bottom falls out in Neil Young’s solo just before the five-minute mark in “Like a Hurricane” on Live Rust. But that’s literally momentary, and the song has a much narrower range of feeling.)

At the end of that initial solo, “Machine Gun” gathers itself up for another vocal section, one of resignation but also warning. Hendrix fashions his narrator as a martyr (“After a while your cheap talk don’t even cause me pain / So let your bullets fly like rain”) and his words combined with Miles’ high-pitched “oooooooooh”s seem to conjure a storm cloud of a solo – diffuse but undeniably threatening, with feedback eventually replacing the backing vocals.

It’s narratively funereal, and in the final verse, Miles sings instead of Hendrix, with the point of view shifting to outside of the battle, offering an obvious but necessary reminder: “He ain’t goin’ nowhere / He’s been shot down to the ground.”

In its deceptively simple lyrical structure, the song begins as an argument against war from a soldier’s perspective, burrows into his psyche for the fight, and – once he’s dead – pulls back to show the damage. It’s hardly profound, but it’s viscerally effective.

After all that over nearly 10 minutes, the coda is almost inevitably a letdown, but it works well enough as a denouement, a place of rest before one final explosion. This is where “Machine Gun” goes to die, spent.

You think you can hear Hendrix’s exhaustion as he nears the end. Yet watching the concert footage, he makes it look almost effortless, foregoing his typical flamboyance and instead barely moving his feet.

I have no doubt, though, that it would be nearly impossible to craft even a wan forgery of that night’s performance. There’s a reason the similarly bravura “Voodoo Child (Slight Return)” has been covered dozens of times, while only a few people (Cox and Miles among them, on 2006’s The Band of Gypsys Return [sic and sic]) have attempted “Machine Gun”:

Hendrix only managed to truly pull it off one time, and ain’t nobody else Jimi Hendrix.

What a timely review of such a chilling performance… one day before the anniversary of his death.

Band of Gypsys is one of those albums I played over and over in high school…. your deconstruction of Machine Gun captures the energy and spirit of the performance superbly.

It is hard to put into words what Hendrix has given us, thank you.

I will now proceed to go cue up Band of Gypsys.