Unbreakable

In the 10 years since I saw it in the movie theater, I’ve regularly planned to return to M. Night Shyamalan’s follow-up to The Sixth Sense. I wanted to see if it’s as strong as I remembered, and – as the writer/director’s star has fallen (and fallen, and fallen) – I was curious how this movie might look in the context of his career.

In the 10 years since I saw it in the movie theater, I’ve regularly planned to return to M. Night Shyamalan’s follow-up to The Sixth Sense. I wanted to see if it’s as strong as I remembered, and – as the writer/director’s star has fallen (and fallen, and fallen) – I was curious how this movie might look in the context of his career.

Sadly, Unbreakable hasn’t held up well. While I think it’s better than The Sixth Sense, Signs, The Village, and Lady in the Water, it suffers from an inability to transcend the conceit. Shyamalan’s movies are never as compelling as their one-sentence pitches. (I have not seen his first film [Praying with Anger] or his two most recent efforts [The Happening and The Last Airbender].)

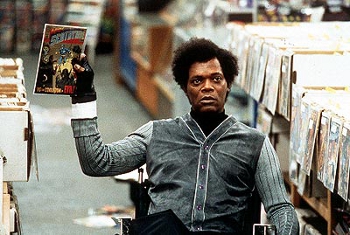

Unbreakable remains a great idea for a superhero movie. The basic idea was to foreground the typically neglected backstory, with the drama coming from the protagonist’s dawning awareness of his special powers, and the disruption they cause to his family and his sense of self. Specifically, Bruce Willis’ everyman David Dunn is forced to confront the implications of the fact that he’s never been sick, and only once been seriously physically harmed. Samuel L. Jackson’s fragile-boned Elijah Price – a comic-book-art dealer – facilitates his enlightenment, as he’s been searching for his opposite, somebody who’s unbreakable.

By not rushing through the superhero “birth,” the movie grounds itself in the mundane and everyday, and makes the fantastic feel more plausible. Price suggests that comic-book stories have some basis in real events and people, and Unbreakable is most successful in showing what a stripped-down superhero might look like. (His “costume” is a poncho.)

And Shyamalan approaches the story with a certain rigor. Dunn doesn’t have super-strength in the Superman way, but he has something close to it. If one’s bones don’t break, and one’s other biological structures can’t be torn or pulled, by extension one can physically do things that normal humans can’t. This is shown in the movie’s weight-lifting sequence, which articulates without exposition Shyamalan’s logic; the audience is given the time to process and comprehend.

There’s one other scene in which the movie’s ideas are given room to breathe, a showdown between father and son in which Dunn’s best weapon is a parent’s threat. The sequence doesn’t exactly work – the writer/director and his performers are just a little off-key – but I appreciate that Shyamalan excavated this moment of domestic tension.

Beyond that, though, Unbreakable is a lost opportunity. Dunn is a wan man, but Willis plays him nearly catatonic. The typically electric Jackson is, outside of his wardrobe, nearly dull. The film’s drab aesthetic seems to have infected the performers and the creator.

Beyond that, though, Unbreakable is a lost opportunity. Dunn is a wan man, but Willis plays him nearly catatonic. The typically electric Jackson is, outside of his wardrobe, nearly dull. The film’s drab aesthetic seems to have infected the performers and the creator.

When Dunn decides to finally try his hand at being a hero, Shyamalan gives him a random challenge with an obvious obstruction, and it’s staged perfunctorily. And that’s the film’s action centerpiece.

All of that would be unfortunate but easier to swallow if Shyamalan had someplace to take his story. The hilariously anticlimactic twist tries to recast the movie as a traditional comic-book battle between good and evil. And that’s followed by a postscript suggesting that Dunn’s real superpower is picking up the phone and calling the police.

The elements are there for a satisfying final act, particularly with the character of Price. His search for a foil is the most psychologically complex and engaging element of Unbreakable, and I love the idea of villainy born of deep neediness. But it’s never meaningfully explored. What does he hope to accomplish by finding his inverse? What does he want to do once he’s found it?

Dunn’s reluctance to accept who he is could also be fertile. By the end of the movie, he seems to have only imagined that his powers can be exploited to forge a bond with his son; he has little interest in the “greater good” that drives most superheroes.

Shyamalan has, then, truncated his story. He seems to have imagined a classic three-act or hero’s-journey arc for David Dunn, but he cuts it off well before its completion.

This is reportedly intentional, but the result is half or two-thirds of a good story. One doesn’t need to stick to the formula, but the formula exists because it works. And Unbreakable feels wrong largely because it sticks so closely to the template until it abruptly ends.

Shyamalan’s movie looks especially weak compared to Christopher Nolan’s Batman Begins, which has a similar interest in the origin story but completes the narrative arc.

Unbreakable had the opportunity to be something similarly good – a thoughtful exploration and examination of the superhero genre through an atypical emphasis on beginnings. It’s a shame it’s missing its ending.

While I agree that all of Shyamalan – s movies are flawed to one degree or another, I disagree with some of your assertions about Unbreakable.

You say: “Dunn is a wan man, but Willis plays him nearly catatonic. The typically electric Jackson is, outside of his wardrobe, nearly dull. The film – s drab aesthetic seems to have infected the performers and the creator.”

Firstly, I think the point of this film is to be a stark, gritty and minimalist rendition of the “superhero genre”, a genre which has suffered greatly from Hollywood’s misguided desire to reproduce the colorful, over-the-top bravado of the comics. While I would agree that Nolan’s Batman films do a somewhat better job at the “gritty-realism” approach to the superhero movie (especially Dark Knight), I also wouldn’t put Unbreakable in the same category. At least, I think it deserves its own subgenre: perhaps the “pseudo-superhero movie.” In many ways, the movie itself is a commentary on the superhero genre, operating from outside it while simultaneously emulating it.

I think without what you call drabness, Unbreakable would stray away from what makes it so interesting. The grayness of the movie and restrained acting is intentional, and I think it works.

Just my thoughts.

I agree that the ending of Unbreakable is problematic, especially in the aftermath of The Sixth Sense. In Shyamalan’s first hit, the twist redefined everything that came before it. The ending of Unbreakable is a surprise, but not such a redefining twist, and so it inspires a “What’s the point?” feeling. Without Shyamalan’s reputation for “I fooled you” endings (or attempts at them), the conclusion could be defended not as an exhilarating twist but as a sobering cold bucket of water to the face: David’s triumphant realization of his powers, his awakening about who he is, is immediately followed by the stomach punch of learning that the person he thought was a close friend was in fact an enemy. This shows the burden on the super hero: that evil is everywhere, and, to quote another super hero brand, that with great power comes great responsibility. In other words, Dunn isn’t done. He can’t beat one bad guy and hang up his poncho. He has to face the reality of evil around him.

So, in the end, Unbreakable would probably be a sharper film without the muddled conclusion. Still, even with that conclusion I think it’s a truly great film that in fact does hold up. And I’d second the thoughts above about the intentionally gritty atmosphere. This is a film filled with characters who are, in a word, depressed because they feel like they don’t quite fit in the world around them. So while the film is indeed a super hero origin story, more broadly it’s also about the importance of knowing where you stand in the world — self identity.