Tool’s Maynard James Keenan Talks the Documentary Film Blood Into Wine

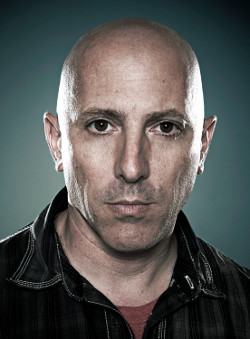

Maynard James Keenan – the frontman for prog-metal gods Tool, the co-leader of A Perfect Circle, and the founder of Puscifer – isn’t the type of person you’d expect to see as the subject of a thorough documentary. He has a reputation for being reclusive, and for jealously guarding his privacy. As he says in the movie Blood Into Wine, “I’m not much of a people person.”

Maynard James Keenan – the frontman for prog-metal gods Tool, the co-leader of A Perfect Circle, and the founder of Puscifer – isn’t the type of person you’d expect to see as the subject of a thorough documentary. He has a reputation for being reclusive, and for jealously guarding his privacy. As he says in the movie Blood Into Wine, “I’m not much of a people person.”

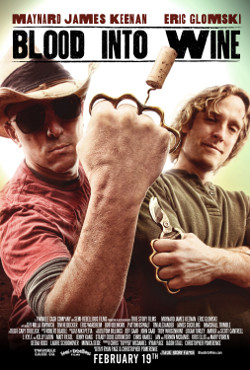

Yet Keenan, along with his wine-making partner Eric Glomski, is at the center of that documentary, a freewheeling but thoughtful mix of wine primer, underdog story, buddy picture, and sketch comedy. The movie is fun and gently didactic, and thankfully it engages in little idolatry. (Those hoping for a Tool movie will be disappointed; although Blood Into Wine doesn’t ignore Keenan’s music career, it’s at best a tangent.)

Keenan often looks uncomfortable in the movie, but that could be a function of once being filmed on the toilet, and of being hectored by a pair of wine-hating talk-show hosts. (More on those things later.) But he is apparently committed enough to his cause – fostering an Arizona wine country, and combating the idea that the state’s climate and terrain can’t produce good grapes and wine – that he’s willing to subject himself to all these indignities, and the public spotlight.

As Keenan told me in an interview last week: “This is an important thing we’re doing up here. If we’re successful with what we’re doing, it’s going to set up a future for more families than we can number. … If you plant vines in this valley, they’re going to taste a certain way; they’re going to be very specific to where they’re from. It’s not a business that you can move to Mexico or China. It’s from here. This is the definition of sustainable and local.”

A Good Story

That Blood Into Wine – premiering February 19 at a handful of sites – exists is somewhat surprising, given Keenan’s nature. The project was sparked by the rock star being interviewed for Christopher Pomerenke’s 2009 documentary The Heart Is a Drum Machine, about the nature of music.

That Blood Into Wine – premiering February 19 at a handful of sites – exists is somewhat surprising, given Keenan’s nature. The project was sparked by the rock star being interviewed for Christopher Pomerenke’s 2009 documentary The Heart Is a Drum Machine, about the nature of music.

But Pomerenke said last week that Keenan’s participation in the earlier film remains a bit of a mystery. “We weren’t entirely sure why he said ‘yes'” to The Heart Is a Drum Machine, he said, “because we were aware that he’s pretty private and doesn’t do a lot of interviews. We suspected that maybe he liked my partner’s last film [Moog, which Wine co-director Ryan Page co-produced] … .”

Not true. Keenan said in our interview that he’d never seen Moog. “I went to some of the actors that they’d been in contact with to see what they had to say about them,” he said.

And Pomerenke said that after Keenan was interviewed for Drum Machine, he asked what the movie was about.

Keenan’s willingness to do Blood Into Wine (and promote the film through interviews) makes a little more sense: The movie – scheduled for a May 4 home-video release, Pomerenke said – could do a lot to build national interest in Arizona wine.

He might be a reluctant face for Arizona wine, but he recognizes that Arizona wine needs a face: “It takes all the pieces of the puzzle coming together to make it all work, in order for someone to discover it,” he said in our interview. “You need a good story, you need a great wine-maker, you need a great farmer. And apparently you need buckets and buckets of cash you dump down a black hole.”

Given the dominance of California wine in American culture, selling the public on Arizona wine requires that good story; it’s a difficult sales job. One has to counter the prevailing wisdom that, as one interviewee says in the movie, trying to make wine in Arizona is like “trying to make wine on the moon.”

The idea for Blood Into Wine came from Drum Machine, for which Keenan was filmed at his Arizona vineyards. Page and Pomerenke pitched Keenan the idea of a documentary about his wine-making business, and “he at first wasn’t really warm to the idea,” Pomerenke said, adding that it took six months to convince him. Keenan said he was merely busy with his grapes and his wines.

The filmmakers and Keenan and Glomski then went about setting the ground rules for the movie. The subjects both wanted their personal lives left out, and Keenan wanted the movie to focus on wine rather than the music career of the celebrity wine-maker. Keenan owns Caduceus Cellars and Merkin Vineyards (in northern Arizona’s Verde Valley), and Glomski makes the wines, with the Tool singer essentially working as his apprentice. The pair co-owns the Arizona Stronghold Vineyard (in the southern part of the state), and Glomski has his own vineyard and winery (Page Springs) in the Verde Valley.

Keenan also said he didn’t want to participate in a dry film. “One of the things that I was pretty specific about is I didn’t want it to be a PBS special, either,” Keenan said. “If we’re going to do it, let’s do it as artists would do it.”

He said that although he was given significant input into the film, he didn’t dictate what was in it. “For us to be in control of the final cut would compromise their vision … ,” he said. “It’s their film. It’s not my film. It’d be like having some producer come in and tell me how to finish the record.”

“We definitely shared with those guys different versions of the edits as they were coming to us … ,” Pomerenke said. “They were kept in the loop how the story was developing. I wouldn’t say there was veto power, but we’re gentlemen. We are artists. This is our film. We’re telling their story like we want to tell it. … [But] we’re people as well, and we want those guys to feel like it was accurately representing them.”

The co-director was quick to point out, though, that “we challenge those guys pretty strongly … .”

Truth Through Staging

“Challenge” is probably too direct, but it’s undoubtedly true that Blood Into Wine is irreverent and not at all interested in maintaining the dignity of wine, wine culture, or even its subjects.

“Challenge” is probably too direct, but it’s undoubtedly true that Blood Into Wine is irreverent and not at all interested in maintaining the dignity of wine, wine culture, or even its subjects.

The movie opens with Focus on Interesting Things, an improvised fake talk show with Keenan as the guest and Tim Heidecker and Eric Wareheim (of Tim and Eric Awesome Show, Great Job!) playing the moronic hosts. Keenan is clearly in on the joke and has dabbled in comedy, including with Puscifer, but the hosts are so immediately insulting to Keenan, his wine, and wine in general that Pomerenke said the Tool singer got “punk’d” a bit. Even knowing it was staged and a joke, it’s hard to imagine not taking the assault at least a little personally.

“We didn’t necessarily want to hurt Maynard’s feelings,” the filmmaker said. But “we didn’t know that Interesting Things was going to get so venomous.” Keenan sometimes appears to be smiling – slightly – but he wears a dumbfounded look most of the time, like he’s been ambushed and doesn’t know how to react. It’s hard to tell from the film what’s acting and what’s befuddlement.

Pomerenke said Keenan was a good sport: “Maynard was laughing, and he didn’t walk off set.” Although some people who’ve seen the movie have said Focus on Interesting Things is “mean-spirited,” Pomerenke said he doesn’t know whether Keenan was as

miffed as he appears. “I’ve never discussed it with him,” he said. “Maynard is a man of few words.”

Pomerenke said the goal of starting the documentary with this comedy bit was to knock Keenan off a pedestal and debunk any Arizona pride – “attacking that right off the bat.”

This opening does announce that the movie shouldn’t be taken too seriously, but it also casts minor doubt on the authenticity of the “real” bits.

To be fair, there’s a pretty bright line between the genuine and the fake. The staged bits are often absurd. Beyond Interesting Things, Bob Odenkirk contributes a ridiculous closing-credits skit. And the reveal that one of Keenan’s responses was delivered while on the toilet – the singer claimed the idea in our interview – offers some jokey context for his awkwardness.

And it’s clearly sincere when Keenan begins to cry talking about his mother, who died in 2003; her ashes were scattered on the vineyard, and “she gets to travel the world now” through the wine, he says in the movie.

But there are moments of uncertainty, as when Pomerenke and Page tell Keenan that they’ve been approached about doing a reality-TV series featuring him. Pomerenke insists the offer was real, but it doesn’t play that way in the film. (Keenan’s response: “Fuck no.”)

“We’re not real orthodox documentarians,” Pomerenke said. “We like the idea of things that are somewhat staged if it can get to a deeper meaning or reveal some sort of truth through the staging.”

Bringing Out the Land

Keenan moved to Arizona in 1995 and said he met Glomski – who returned to Arizona after working in the California wine industry, ascending to co-wine-maker at David Bruce Winery – in 2002 or 2003. Their joint wine endeavors started shortly thereafter.

Keenan moved to Arizona in 1995 and said he met Glomski – who returned to Arizona after working in the California wine industry, ascending to co-wine-maker at David Bruce Winery – in 2002 or 2003. Their joint wine endeavors started shortly thereafter.

While Blood Into Wine’s subjects aren’t pioneers – Keenan guessed that contemporary vineyards in Arizona date back at least a dozen years – they are likely essential to building a market for Arizona wine.

Keenan’s fame is the obvious impetus for the movie, which will expose a lot of people to the idea that the state has a lot to offer wine and wine consumers. And his financial resources are also critical. “You spend $10 million to make one” million dollars in the wine business, Keenan told me. “I’m definitely not out of the hole by any stretch. I believe in this thing so much that I’ve dumped everything into it.”

The wine-makers have had to deal with rough climate. Despite Arizona’s reputation as a baked desert, “we have more problems with cold than we do heat,” Keenan says in the movie.

There are also critters that can destroy crops.

And there are bureaucratic obstacles, from water rights to branding. Although it’s not in the movie, Keenan said he’s now battling the federal Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau, which regulates how wines are presented. “They’re still trying to fight me on the name of my wine, although they’ve approved every one of my labels,” he said. They want him to change his name and logo – the snakes and staff of caduceus are often confused with the medicine-related Rod of Asclepius – “having let me develop this brand. … They say I’m implying that it’s medicine.”

But there are also the basic challenges of wine-making. Finding grapes that will grow well in Arizona, Keenan said, has been a “crapshoot.” They looked for hardy fruit and have planted varieties from “Bordeaux, Italy, southern Rhone, northern Rhone, Spain – just because the terrain here mimics some of that. So we’ve planted pretty much everything you can think of.”

It’s critical to understand that Keenan and Glomski aren’t interested in trying to make California-style wines in Arizona. They think the land gives the grapes and therefore the wine a unique character.

When they were getting started, Keenan said, they brought out experts from California, but they weren’t very helpful. “This ground has nothing to do with that ground,” he said.

Expressing the land, he added, is “the most important part. … It’s something that we’re missing [as a culture], the connection to the ground.” The core of the film, he said, is “connecting with where you are.”

“My wines are an expression of a place that I call home,” Glomski says in the movie.

Much mass-produced wine, Keenan said, does not meet that goal, with flavors achieved through processing rather than viticulture. “What they’re doing to it has nothing really to do with the wine,” he said. “There are things that are outweighing what’s happening in the bottle. … It could be made anywhere. So as a business model, great, but as a sustainable product … .”

Bringing out the characteristics of the soil, climate, and farming techniques – collectively known as a wine’s terroir – will take a long time. Keenan gave the example of Cabernet grapes grown with a 900-foot difference in elevation, with one vineyard on flat land and one on a slope in a different part of the state. “It’s going to take us a few years to really figure out what the unique profile for the grapes are up here in northern Arizona. … ,” he said. “There’s two Cabs and they taste similar. Why do they taste similar? They should be polar opposites just based on the elevation and the temperature swings on those two sites.

“Two different parts of the state are definitely presenting two different styles of wine,” he continued. “That they are not different enough in characteristic might just be because we treated them in a similar way in the wine-making process. Maybe we should have used different kinds of yeast.”

Keenan has produced five vintages of Caduceus, with 10 red-wine styles and one white. Prices range from $18.99 to $100 a bottle.

For the time being, Keenan is having “custom crushes” done for him at Glomski’s winery, but he has almost finished his own winery, at which he hopes to “dabble” this year.

“The biggest, most important step for me in the wine-making process is going to be to make a lot of mistakes,” he said. Glomski will continue to make most of the Caduceus wines, while Keenan will experiment with “small batches that I just assume I’m going to screw up.” Glomski’s role will be “saving it from the brink when it’s about to go horribly wrong, but allowing me to make mistakes.”

Keenan also said that Glomski will be his primary wine-maker for the foreseeable future. “I’ve got crazy ideas that he would never explore,” Keenan said. “I’m kind of like … Curly to his Larry and Moe.”

Getting Out of the Way

Keenan’s passion for wine-making is evident both in the movie and over the phone. When he talks about music, however, you might fear that you’ll never have another album from Tool or A Perfect Circle. The singer clearly wants no part of contemporary celebrity culture.

“You’ve seen how popular reality TV is,” he said. “People don’t care about the person. They want to see them self-destruct. And that’s partly what it is with the entertainment industry. … Unless it’s tragic, who cares?”

People might like music and enjoy the songs, he said, but fundamentally “they want to see you overdose. They want to see you self-destruct and come apart. … I’m not a martyr. I have no intention of sacrificing myself for the evening news.”

But while there are no imminent releases from any of his bands, Keenan said he hasn’t given up music for wine. “If it’s a positive, healthy experience, then it’s always going to be a part of my life,” he said. “I’m not going to abandon my brothers. I just think we have to re-think what the healthy steps are.”

And he sees parallels between making music and wine. “It’s just a matter of perception, and how you perceive the world around you,” Keenan said. “The whole listening process and the whole responding process.”

Bo

th involve “getting out of the way and allowing things to occur. Of course, nudging them along with your personality and your perceptions in the world. … You’re allowing this terroir, or this site, or this grape to speak for itself, and then you nudge in the direction that you think it should go, but you let it speak to you first.”

For more information about the movie, visit BloodIntoWine.com.

(This article originally appeared, in slightly different form, in the River Cities’ Reader.)

Great article Jeff. I always thought Keenan was one of the more interesting lead singers to come around in a long time and I’m very impressed to his dedication to trying to create a “sustainable” industry in a rough climate.