…Around

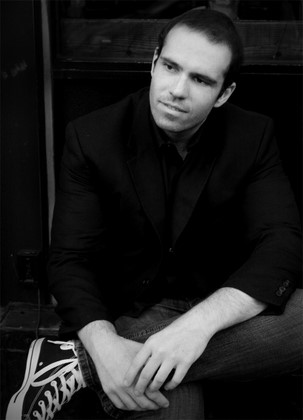

Writer/director David Spaltro’s debut feature …Around concerns a film-school student who lives out of train stations in New York City, and the movie has such a distinctive, Pollyanna view of homelessness that it’s either completely divorced from reality or born of some charmed experience.

Writer/director David Spaltro’s debut feature …Around concerns a film-school student who lives out of train stations in New York City, and the movie has such a distinctive, Pollyanna view of homelessness that it’s either completely divorced from reality or born of some charmed experience.

In an interview last month, Spaltro called …Around “a very personal story to me. I never use the term ‘biography’ or ‘autobiography,’ because I think even if you’re being extremely honest, when you start writing or creating anything, it’s always fiction in some way, because you can only tell your perspective or your memories.”

That’s a roundabout way of saying that Spaltro lived out of a train station while going to film school. He put his tuition on credit cards, aiming to pay the minimum each month, but “then I realized I’d have no money for living.” He read an article about a student calling a public library home, and … there you go.

“Part of me thought of it more as an adventure,” Spaltro said of his transient experience as a 19- and 20-year-old. “It was something I was always choosing. I didn’t have to go to school. I didn’t have to do it that way. … [And] there’s probably also no better place than New York City where you can pull something off like this.”

Spaltro didn’t think of his experiences as source material for a movie, and he said his friends were shocked. “How could you possibly not have a story?” they asked him. But, he said, “with something that happens to you, you don’t quite see it as interesting. … Who would want to see that?”

Spaltro didn’t think of his experiences as source material for a movie, and he said his friends were shocked. “How could you possibly not have a story?” they asked him. But, he said, “with something that happens to you, you don’t quite see it as interesting. … Who would want to see that?”

In an ideal world, lots of people. …Around is a compelling story told with confidence and filmmaking moxie. Sure, it has a lot of the hallmark shortcomings of a first film, but it rewards those who watch with a forgiving heart. “I think my real film school was …Around,” Spaltro said. (The movie is available for streaming on Amazon and Netflix.)

Shot in September 2007, the movie had a production budget of $150,000 – financed on 40 credit cards, Spaltro said. “My credit score probably looks like a batting average right now,” he added.

The director’s handling of such a large movie is impressive. By any standard, it has a large cast and many locations (190 by Spaltro’s count), and 105 minutes is a lot to manage if you’ve never made a feature before. He did it big, he said, because “I didn’t know if I’d ever get a chance to do it again. … I don’t know if I’d ever be so brave again.”

Beyond the accomplishment of making such a sprawling film as a first feature, …Around works because of a specific, rich central character. In a ballsy move, the Spaltro-based protagonist, Doyle (Robert W. Evans), is a bit of a prick. He’s appealingly wry but too quick with quips, always guarding. “You sort of build a double life, because you don’t exactly advertise you’re doing this,” Spaltro said of being a homeless film student.

Beyond the accomplishment of making such a sprawling film as a first feature, …Around works because of a specific, rich central character. In a ballsy move, the Spaltro-based protagonist, Doyle (Robert W. Evans), is a bit of a prick. He’s appealingly wry but too quick with quips, always guarding. “You sort of build a double life, because you don’t exactly advertise you’re doing this,” Spaltro said of being a homeless film student.

Doyle is also highly self-involved, and even his rescue missions are nakedly selfish. Most damningly, he acts continually entitled, whether he’s shoplifting food, running up credit-card debt he has no means to pay off, or pressing way too hard for dinner with a woman he likes.

Spaltro suggested that he’s surprised that people don’t recognize that Doyle stands in for him. “I don’t know if they just missed that it’s very autobiographical, or they just don’t accept that it is, but sometimes people will say stuff about the character … , like, ‘Wow, what a sociopath,’ or ‘Oh, man, what a fuck-up,'” he said.

It’s not an inappropriate reaction, he concedes: “There are times when I look at it, and I go, ‘Wow, what an asshole.'”

None of which means that Doyle is much different from the rest of us at a certain age. It’s just that we rarely see this side of growing up in movies; Spaltro is focused on an uncomfortable period of development – presumably adult but behaviorally childish – that’s more embarrassing as we grow older. The conception and portrayal of Doyle are affectionate but clear-eyed.

Evans is particularly strong – Doyle’s woundedness is never quite hidden by his mask – and he’s nearly matched by Molly Ryman (as the love interest) and Marcel Torres (as the best friend). The movie’s love story and mother-son dynamics are detailed and feel authentic.

Evans is particularly strong – Doyle’s woundedness is never quite hidden by his mask – and he’s nearly matched by Molly Ryman (as the love interest) and Marcel Torres (as the best friend). The movie’s love story and mother-son dynamics are detailed and feel authentic.

The framing device – Doyle is telling his story on a bus out of New York City – comes off as a self-defense mechanism, as the narrator abdicates his responsibility to open his tale well and allows that he might be a bad storyteller. But Spaltro’s movie is surprisingly tight for something that feels so ramshackle and episodic … and something by a first-time writer/director … and something based on his own life. (Few of us are good at trimming our own stories.)

There are, naturally, missteps. Spaltro is overly fond of a fish-eye effect, and the script could have used a good scrubbing. The movie mocks artistic pretension and cliché – a film proposal about a black gay prostitute with HIV, and a spare painting that barely exists – without itself getting far beyond them. The literal house of (credit) cards that Doyle builds, for instance, is a trite but effective metaphor – until it falls down in slow motion. In the brief sequence with the aforementioned painting, Spaltro shows the artist explaining the existential meaning of her work to Doyle, who stupidly says he’d like to see it when it’s finished. You can likely predict what happens next: The indignant painter says the work has been done for months, and Spaltro follows that with a shot of the painting itself – a too-easy knock on immature portentousness.

Spaltro often seems to assume that because things happened, they’ll be credible and won’t be judged independent of their truth. Doyle’s Jersey-stereotype father couldn’t be sketched more broadly, but Spaltro insists that the character is actually underplayed. “Truth is stranger than fiction,” he said. “There’s a lot of word-for-word stuff.” That probably accounts for much of the clunky dialogue; good art rarely mimics life verbatim.

But it would be churlish to focus on the movie’s flaws. Like most first films, …Around is best evaluated in context and prospectively – seeing what it gets right considering the circumstances of its creation, and looking forward. It’s not faint praise in the least to say that …Around is a strong testament to Spaltro’s potential as a filmmaker.