A submission to Counting Down the Zeroes, a project by Ibetolis at Film for the Soul.

A warning: If you’re bothered by spoilers, images of fellatio, or discussions of fellatio, avert your eyes.

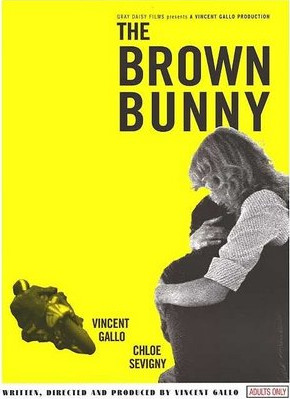

The Brown Bunny

The Brown Bunny gave Roger Ebert cancer, and it features a real blowjob. And the girlfriend is dead.

The Brown Bunny gave Roger Ebert cancer, and it features a real blowjob. And the girlfriend is dead.

In 18 words, I’ve summarized the hullabaloo surrounding (and the post-climactic revelation of) Vincent Gallo’s shockingly vain vanity project from 2003. I can even spare you from the “boring” parts of the movie – basically the first 80 of its 93 minutes – and help you indulge whatever prurient curiosity you might have by pointing to an in-depth description/analysis and video of the oral-sex scene.

But the film as a whole is actually oddly fascinating, especially in the context of its initial critical drubbing and the filmmaker’s reaction to that reception.

Gallo starred in, wrote, directed, edited, and produced The Brown Bunny; shot some of it; did the costumes, makeup, cinematography, etc.; and presumably ejaculated in it. He debuted it at Cannes, and Ebert called it “the worst film in the history of the festival.”

But the esteemed critic gave three stars to the revised movie upon its American theatrical release:

“Gallo went back into the editing room and cut 26 minutes of his 118-minute film, or almost a fourth of the running time. And in the process he transformed it. The film’s form and purpose now emerge from the miasma of the original cut, and are quietly, sadly, effective. It is said that editing is the soul of the cinema; in the case of The Brown Bunny, it is its salvation.”

The leaner version of the movie is still a slog. The first hour has Gallo’s Bud Clay, a motorcycle racer, traveling across the country in his van. At the beginning, he invites a gas-station clerk named Violet to join him on his journey. She reluctantly agrees – leaving a note on the gas-station door – but Bud bolts after dropping her off to pick up her things.

Bud drives. He stops at the childhood home of a woman named Daisy, and her mother wonders why she hasn’t heard from her in so long. Bud is cryptic about everything – what he knows about Daisy’s whereabouts, why he and Daisy never had children, whether they’re still a couple. He drives some more. At a rest area, he tentatively comforts/cuddles Lilly. Bud drives. In Utah, he rides his motorcycle on the salt flats. He drives some more. In Las Vegas, he buys lunch for a hooker named Rose. Bud drives.

It sounds dull, and it is – but that’s clearly the intended effect. The opening shot of the movie is a motorcycle race, and we see Bud speeding around the track, over and over and over again. The Brown Bunny then delivers on this implicit promise of tedium and repetition.

Bud’s travels are filled with interchangeable logos, signs, brands, and landscapes, and he hopes that women with flower-based names can be easily swapped, too. There’s a palpable need in him – the way he says “please” to the gas-station attendant (twice) is pathetic – that he can’t satisfy. Everything is transient in Bud’s world, but nothing ever changes. And it’s all empty.

![Names of flowers [sic] brown-bunny-4.jpg](https://www.culturesnob.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/brown-bunny-4.jpg)

The Brown Bunny was shot in a deliberately artless, aggressive documentary style – the hand-held camera is often struggling against the sun, with an amateur’s mastery of focus and framing – and the combination of its aesthetic with the movie’s languorous pace is surprisingly hypnotic. I didn’t give a damn about Bud, but I shared his weary state of mind.

He reaches Los Angeles and knocks on Daisy’s door far longer than politeness allows. A neighbor tells him nobody’s there. He leaves a note. In his hotel room, Daisy – before now only glimpsed, at roughly the 30- and 60-minute marks in the movie – appears in the form of Chloë Sevigny. They talk vaguely, ’round and ’round. She blows him.

Even if you entered the film blindly, you long ago figured out that something was off, and I’m guessing that any audience is way ahead of Bud in realizing that Daisy is no longer among the living. If her through-a-locked-door entrance in the hotel room wasn’t enough, during the fellatio Gallo offers another clue: Bud literally has a hand in his own sexual pleasure.

Perhaps Gallo has difficulty keeping it up, or maybe he can’t get off without leading the charge himself, but I doubt it. This seems to me a telling detail: What we are watching isn’t an act of love or a memory; it’s masturbation.

Well, of course it is, and therein lies the artistic resonance of The Brown Bunny. The film’s protagonist is a reflection of his creator, and they share an extreme narcissism: Just as Gallo uses his “art” to get blown, Bud turns his girlfriend’s death into a showcase for his insecurities – and to get off. Daisy explains after their encounter that she was gang-raped at a party and choked on her vomit, and Bud saw the attack and sheepishly walked away; he did nothing to help her, yet his intervention at any point probably would have saved her life. Bud’s guilt wells up, but his denial is strong; he casts the rape as infidelity on her part. This is an almost pathological level of self-involvement.

I’m certain that Gallo recognizes Bud as a selfish coward rather than a tragic figure of loss. But I think he sees potential in his main character. “Bud,” particularly in the context of the writer’s flower-naming scheme, suggests mere immaturity, while “Clay” is malleable. Following 80 minutes of nearly nothing, The Brown Bunny’s remainder is a tight knot of self-love and self-loathing – a suggestion of dawning awareness.

I’m less sure, though, that Gallo consciously understands how the movie illuminates his own cinematic and sexual self-indulgence. But I think that like Bud, he has an inkling of it, somewhere.

I doubt it’s a coincidence

, for example, that after pouring his life into the movie, Gallo declared: “It is a disaster and a waste of time.” Despite that unequivocal dismissal, he went back and re-cut the movie.

There’s further evidence of a nearly violent ambivalence in Gallo. The DVD for The Brown Bunny includes two trailers: One shows contempt for critics, reveling in Lisa Schwarzbaum’s incorrect Cannes prediction that “no one in America will ever see one frame of this film,” and the other shows contempt for the audience, revealing the movie’s “secret” on the left side of a split screen while showing its meandering manner on the right.

Gallo has vacillated between loving his film and hating it, between saying “fuck you” to the critics and agreeing with them, between wanting an audience and doing his best to repel it. The movie itself documents a struggle within Bud. Everything around the movie shows the wrestling match between Gallo and The Brown Bunny.

None of these conflicts is terribly interesting on its own, but together they’re pretty compelling drama.

Jeff,

I’ve been wanting to check this film out for some time now, but just haven’t gotten around to it yet.

But this article makes me wonder:

Have you seen any of John Cassavetes’ films?

I couldn’t tell you why, but after seeing “The Killing of a Chinese Bookie” on the Sundance Channel many moons ago, it’s become my favorite movie.

From what I gather, most hardcore Cassavetes fans were unimpressed with the film (I’ve only seen bits and pieces of “A Woman Under the Influence” and “Opening Night”).

There are two different cuts of the film. The shorter one is probably the better of the two, but the longer version explains more.

But judging by this review (and assuming you haven’t already seen any of his movies), I think Cassavetes’ work might be something you’d be interested in.

Same with Monte Hellman.

Yada Yada…Existentialism…Yada…

What do you think about the idea that the whole trip has been inside his head? That Daisy was just an unrequited crush, Violet represents his stuck-in-adolescence sexuality, the Lemons represent family he never had, Lilly is his distant (now likely dead) mother, and Rose is the daughter he and Daisy never had. It would certainly make this movie more understandable (in terms of why it was put together the way it was). Anyway, I didn’t think it was as terrible as the internets had led me to believe.

hinty: If the whole trip (and hence the whole movie) takes place in his head, then there’s no objective reality, and the whole thing is kinda pointless outside of the experience of watching it. (Many would say it’s kinda pointless anyway.)

I would, however, say that whatever objective reality there is in the movie is intermingled with delusions and fantasy. I believe there are things in the movie that happen outside Bud’s head, but they’re shown from his warped perspective.