A submission to Counting Down the Zeroes, a project by Ibetolis at Film for the Soul.

I’ve previously written on Memento’s opening shot, and – if you’re brave – I’ve also published a fragmentary, aborted draft of a piece on the movie. But this essay is fully fresh.

And it should go without saying, but people are sensitive: Kal Pen killed himself on House. This essay assumes that you’ve seen Memento and have at least a vague recollection of its particulars.

Memento

Memento is such a triumph of tricky narrative structure that it’s difficult to get (and keep) a grip on what happens, let alone the objective truth of its protagonist’s past. Christopher Nolan’s second feature, which he wrote and directed based on his brother Jonathan’s short story, seems perpetually slippery and elusive.

Memento is such a triumph of tricky narrative structure that it’s difficult to get (and keep) a grip on what happens, let alone the objective truth of its protagonist’s past. Christopher Nolan’s second feature, which he wrote and directed based on his brother Jonathan’s short story, seems perpetually slippery and elusive.

I’ve seen it at least six times since it was released in the U.S. in 2001 (it debuted at festivals in September 2000), and even though I know it well, each time it repeatedly throws me off. The movie’s closing line – in context, a sick joke by Nolan – is an excellent summary of how I feel watching it: “Now … where was I?”

Yet with enough familiarity and perspective, it becomes clear that there’s no great mystery: Leonard killed his wife by accident because of his “condition,” and he will hunt down one “John G.” after another knowing, somewhere in the dark well of his mind, that he’s done it before and will do it again. Once you accept that – and therefore discount ambiguity as the source of the movie’s lasting appeal – you can see that Memento’s magnificence is its structure: a near-perfect match of form with content.

Throw-Away Human Moments

The plot – the narrative proper that the audience sees – and the premise can be reduced to these essentials: Leonard’s brain does not make new memories since an injury he sustained while trying to stop an assault on his wife. Hungry for vengeance, he tattoos himself with reminders and clues that he believes will lead him to his wife’s surviving attacker: “John G.,” or perhaps “James G.” Teddy, a crooked cop plotting for a $200,000 payday, manipulates Leonard into killing a drug dealer. After the murder, Teddy tries to placate an agitated Leonard by telling him that this isn’t the first “John G.” he’s offed. Natalie, the drug dealer’s girlfriend, knows that Leonard had some role in her boyfriend’s disappearance, and she plays him, as well, getting him to beat up a man coming after her for that missing $200,000. Teddy, meanwhile, hangs around, trying to get the money sitting in the trunk of the car Leonard is driving. What Teddy doesn’t know is that Leonard has set him up as his next “John G.” Leonard kills Teddy.

All of those things are evident on a first or second viewing, and Nolan’s direction and tight script are stunningly lucid for a movie with the potential to be disastrously confusing. He trusts the audience to keep up, and he also respects it by playing fair – something that can’t be said for most “puzzle” movies. His opening shot succinctly and elegantly reflects the film’s conceit, themes, and architecture.

Memento’s other pleasures are myriad, starting with an authentic performance by Guy Pearce and a gloriously inauthentic performance by Joe Pantoliano. Pearce’s Leonard is a mix of simultaneous certainty and uncertainty, and Pantoliano’s Teddy projects a false cheer that constantly casts his motives into doubt. Carrie-Anne Moss, a year after her breakthrough in The Matrix, plays guarded in a way that leaves room for Natalie’s poignancy and her dangerousness without seeming under-drawn.

And this ridiculously high-concept thriller about a vengeful man who can’t remember, with a story whose leaps through time look like a rainbow when diagrammed, nails its human moments large and small: from the gently heartbreaking scene of Sammy’s wife telling him repeatedly that it’s time for her shot to the efficient, accurate sketch of a comfortable marriage when Leonard asks his wife why she’s reading that book yet again. It’s full of lovely detail: When Leonard, with a prostitute, is trying to re-create the night of the attack, you can make out a tattoo that reads, “She is gone.”

Nolan also articulates his themes without belaboring them, which is a bit of a surprise given his annoying habit of repeating and underlining major concepts (especially the obvious ones) in his Batman movies. Leonard’s “How am I supposed to heal if I can’t feel time?” gives the audience an emotional sense of what it’s like to live with his condition, and it also gives voice to a grief he rarely has the opportunity to indulge because of his situation.

Blunt Clues

But let’s not kid ourselves: No matter how nuanced Memento is, what remains alluring to many people is trying to figure out the movie’s reality – in particular, the facts of what’s euphemistically called “the incident,” the nature of Leonard’s condition, and how the mythology he regularly repeats relates to them. Is the Sammy Jankis story accurate, or is he a convenient stand-in for Leonard? Is Leonard’s condition physical, or is it a wall he built to keep horrors safely hidden?

On this front, Memento really isn’t coy. It’s true that the audience is offered wildly different back stories by two unreliable narrators: Leonard can’t tell you what happened five minutes ago, and he pieces his tattoos and notes and Polaroids together to give himself a sense of understanding, control, and purpose; Teddy is using Leonard for selfish ends. In light of that, it’s reasonable to be agnostic.

But the movie teaches us that Teddy, while thoroughly weaselly, is almost certainly telling the truth. When Leonard figures out that Burt has rented him two rooms, the hotel desk clerk fesses up. Leonard thanks him for his honesty, and Burt responds that he has no reason to lie; Leonard will forget the dupe in a matter of minutes. That sets up Teddy’s revelations.

Teddy has no motive for lying to Leonard in the final scene. He claims that Leonard’s wife – a diabetic, he says – survived the attack, and that Leonard killed her by accidentally administering an overdose of insulin. Teddy helped him find the real “John G.” and took a photo after Leonard killed him. (We see the picture at two points.) Teddy realized that Leonard never processed his success and began scheming. (Leonard asks Teddy whether the man he just killed was part of a drug deal, and after a quick denial, he says, “Yeah. That, and your thing.”)

Yes, Teddy lies to Leonard (or tries to trick him, such as the many times he attempts to get access to the Jaguar’s trunk) when he wants something. Here, though, he has nothing to gain. In fact, he signs his own death warrant, and while he doesn’t realize it, he certainly should know that confronting Leonard with the unpleasant truth has its risks.

His miscalculation is in his assessment that Leonard isn’t capable of murder without some help. “I should kill you,” Leonard says, pointing a gun at his neck. Teddy casually pushes the weapon away, silencing an ominous cue on the soundtrack. “Quit it,” he says. Teddy doesn’t recognize that while Leonard doesn’t kill out of spontaneous anger and hasn’t killed without a guiding hand, he can find the next “John G.” on his own. Teddy practically puts himself on a platter by saying that his full name is John Edward Gammell.

If you still doubt that Teddy should be believed, Nolan offers two blunt visual clues: For a split second, Sammy Jankis becomes Leonard Shelby in an institutional setting, and Leonard injects his wife, despite his claim to Teddy that she didn’t have diabetes. (Note how many times Leonard says he hates being called “Lenny.” Note, too, that “Lenny Shelby” and “Sammy Jankis” both have five letters in the first name and six in the last.)

You could argue that these are visual representations of Leonard’s baffled brain – trying to resolve the conflict between Teddy’s tale and his own. But Sammy turns into Lenny in a story that Leonard is telling – and that comes chronologically before Teddy confronts him. If there is a discernible “true” narrative, it must be Teddy’s.

It’s more of an open question whether Leonard is physically capable of creating new memories. But in that crucial sequence when he decides to punish Teddy, Leonard slips in his internal monologue: “Can I just let myself forget what you’ve told me?” (Emphasis added.)

And this is as it should be. Leonard is only resonant as a character if he’s blocking new memories as a coping mechanism for what he’s done – a way of refusing to accept responsibility. Otherwise, he’s just a good narrative hook.

The Genius of Cruelty

What remains is the real source of Memento’s enigma: that mathematical structure.

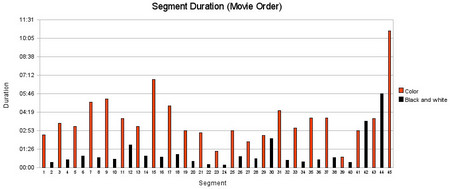

Excepting the closing credits, the movie is composed of 44 discrete segments, alternating between color and black-and-white. It opens in color, with Teddy being killed, and the color segments jump backward in time; each color bit begins just short of where the next one (in movie order) ends. The black-and-white portions, meanwhile, move forward through time. The final section starts in black-and-white and shifts to color after Leonard kills the drug dealer.

You could coarsely say that the color movie begins at the end and goes backward, while the black-and-white starts at the beginning and moves forward, and they meet at the end of the movie in the middle of the story. (Here, you have my permission to throw up your hands in frustration. Or you could read Salon’s analysis for as clear an explication as you’ll find.)

But “middle” isn’t accurate. On a story level, very little happens in the black-and-white sections; they’re mostly table-setting – Leonard in a hotel room talking on the phone, providing exposition and background and context to the audience. Totaling less than 25 minutes, they take up roughly 22 percent of movie’s running time.

They’re narratively unnecessary, in other words, but they are important to the movie’s rhythm. (For purposes of this chart, the hybrid color/black-and-white scene is broken into its black-and-white and color parts.)

They’re also critical to its strategy. The black-and-white sections are generally brief – the shortest is 11 seconds, and only five of the 22 are longer than a minute – and they mostly serve to disorient. The aesthetic leap from color is matched by a different soundtrack, anxious and paranoid, and the hotel room becomes stale and claustrophobic. As you focus on these bits, the previous scene begins to fade. And before you can acclimate, you’re back to color.

Staying with the movie would be hard enough without these interruptions. The conceptual genius of Memento resides in a structure that puts two sections of story between connection points. Scene A starts, and Scene A plays out; Scene B starts, plays out, and then ends where Scene A starts. You’re trying to figure out what’s happening now, and you’re also trying to remember where the earlier color scene began. This creates continual confusion – no matter how many times you’ve seen the movie.

The cruelty of Memento is that it inserts a basically superfluous black-and-white section between each pair of color segments. On average, the viewer is forced to wait more than seven minutes to have the previous scene put in any context.

The result is the movie’s coup: an almost subliminal empathy with Leonard. You relate to him because you’re similarly bewildered, never sure of where and when you are. And that makes the movie’s reveal all the more exhilarating and troubling; the audience knows intellectually that Leonard should not be trusted, but it’s invested in him.

Played Straight

A fair question with any fractured movie is how it would play straight. A related issue is whether the convoluted structure is necessary, or if it instead masks deficiencies.

Because Memento included a chronological version of the movie in the 2002 “limited edition” DVD package, those questions are particularly appropriate.

The re-edit wasn’t what I’d hoped for, in the sense that it arranged the film’s segments chronologically instead of re-cutting them into a seamless whole. The overlapping of the beginnings and endings of scenes remains – a reminder of the original structure that makes it difficult to evaluate this version on its own.

But I doubt any chronological cut would work as a stand-alone movie. Those black-and-white sections would play disjointedly when strung together, and their relative lack of action would make them tiresome. They’re designed as inserts within the main action, and they die outside of that context.

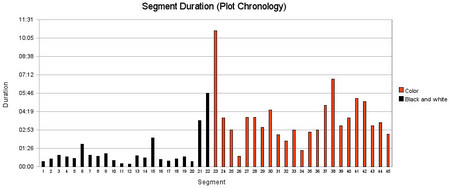

Graphing the duration of the chronologically ordered segments, it becomes visually obvious that the rhythm of the movie is also problematic – a bunch of brief scenes followed by a bunch of long ones. (Again, the black-and-white-to-color segment is divided in this chart [segments 22 and 23].)

More crucially, the tonal effect is a shift from uptight and uneasy in the black-and-white segments to something more relaxed and open in the color sections – an inversion of the story’s natural tension.

Still, the chronological version is instructive.

Instead of emphasizing uncertainty about what’s going on and about Leonard’s condition, those questions are resolved in the first 35 minutes.

You spend the first 20 minutes or so with an obviously unwell Leonard holed up in a hotel room, and you pay more attention to the voice-over narration – such as that joke about reading the Bible religiously. To whom is Leonard talking here? If it’s himself, that speaks volumes about his unbalanced mind.

And then he kills somebody, and then Teddy comes along and tells him he’s deluding himself about his past and his present. Leonard gets angry and sets in motion a plot to kill Teddy. The remainder of the movie becomes an exercise in suspense, as Teddy keeps returning – hungry for that money – even though his license-plate number is tattooed on Leonard’s thigh, marking him for death.

In this conception, Memento also becomes a character study of a person Natalie accurately describes as a “sad, sad freak.” Without a single added shot or line of dialogue, it becomes a different movie, and a clearer one.

But it’s also a lesser film, issues of pacing aside. Memento’s form is its function, mimicking the experience of the main character in its audience.

Leonard tells his wife that “I always thought the pleasure of a book was in wanting to know what happens next.”

She disagrees, and so does Memento. Its pleasure lies in already knowing what happens next, but not being sure how we’re going to get there, or why. It’s about being as lost in the world as Leonard.

What I still do not understand is why Leonard comes out of the Discount Inn from three different rooms total that are his room; in the beginning of the movie he looks out of his window from his room at room 304. Room 304 is his room then throughout the movie. At the end of the movie, which is actually the beginning of the story, he leaves a room on the first floor, room 21. Birt tells him he has rented him two rooms, so what is the third room? I also do not understand how his wife actually died and what those short clips are of her running to the window and going around the house to sit. If anyone knows I would greatly appreciate some clarification. They seem to mirror his actions in the abandoned building as he waits for the drug dealer who he believes is his wifes murderer.