We were in the play area of the department store – most likely building things with Legos – and two girls were taking great delight in excluding me. They were speaking a language I didn’t understand, and it wasn’t exactly a private conversation. They would glance my way during their exchange and occasionally laugh. I felt mocked, which was exactly what they wanted.

We were in the play area of the department store – most likely building things with Legos – and two girls were taking great delight in excluding me. They were speaking a language I didn’t understand, and it wasn’t exactly a private conversation. They would glance my way during their exchange and occasionally laugh. I felt mocked, which was exactly what they wanted.

They were speaking Pig Latin, I figured out later.

Of course, Pig Latin is only effective as a private language through a certain age, but we update and upgrade our codes throughout our lives.

Sometimes it’s the equivalent of a secret handshake, a way to establish common ground with strangers. If, for instance, you’re in a group of people you don’t know terribly well, you might invoke a profession that’s part analyst and part therapist. Those who laugh or smile are obviously fans of Arrested Development, and you can trust their good taste.

Often we use them to communicate something private while out in public. We will often talk about people in their presence – much like those two girls from my childhood – through references that will mean nothing to anybody but us. (Yes, we’re rude like that.)

Mostly, though, our code is simply a confirmation of intimacy, a shorthand that says, “Nobody knows me better than you do.”

What struck me recently is that the language between me and Bride of Culture Snob is based almost entirely on popular culture, with the broadest possible definition of “popular.”

The phrase “I’ll tell your sister,” for example, is an acknowledgment of correctness drawn from Yoda’s dying words in Return of the Jedi. If we have some disagreement about facts, that’s what the conceding party says to ultimately admit defeat.

There are a few basic principles here. First, the reference either needs to be obscure enough or decontextualized enough that it will not be recognized by most people. Second, there should be some sort of joke at work. “I’ll tell your sister” is funny because neither of us has a sister. Third, there should be some fondness in the reference, because the phrase should be meaningful to the shared history. (We both grew up with the original Star Wars trilogy.)

All of this is preface to sharing one of the odder tricks in our bag.

In a conversation, an abrupt shift to a completely different topic is indicated by the word “monkeys.” It is essentially a warning that a non sequitur is coming, and that one should not expend any energy figuring out what relationship Statement A has to Statement B; they have no relationship.

E.g.:

Me: “The sky is very blue today.”

You: “Yes. Quite pretty.”

Me: “Monkeys. My ass is on fire.”

Variations include “not monkeys” and “mostly monkeys” and “almost monkeys.” These are used to indicate relationships that are tenuous or not immediately apparent.

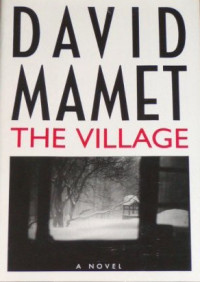

The strange thing about “monkeys” is that it doesn’t belong to a cultural artifact we both adore; it comes from a book that neither of us finished: David Mamet’s The Village, first published in 1994. Bride of Culture Snob read further than I did, but I doubt either of us got past page 100.

Here’s the relevant passage, from pages 43 and 44 of the edition I own:

“The ass-end of the school bus stuck out of the garage. The rain beat on its roof. And when they were not working, they could hear it up by the hood, up in the garage. Marty was working on the engine, and his son, John, sat at the counter, on the metal stool, supposedly engaged in his schoolwork, but listening to the men; and they knew he was listening, and did not care.

“Marty came out of the engine, and sighed, straightening up. ‘ … the monkeys,’ Carl said.

“‘ … uh, yuh, the monkeys,’ Marty said, softly, as he walked to the counter. He held his finger up, as a sign, to Carl, who stayed back at the bus: No. I haven’t forgotten.”

I have no idea whether there are any monkeys in The Village, and it’s possible one of us flipped to this point in the novel, read this passage in isolation, and was so baffled that it was shared and immediately entered our private lexicon.

(Postscript: Bride of Culture Snob thinks she might have finished The Village. I’m skeptical. But if I’m wrong, I’ll tell her sister.)

Great topic! This is something I’ve thought about quite a bit, actually.

http://www.patchworkearth.net/Clu%20-%20Chapter%201-2.html

“We speak our own language, don’t we? A secret code. That last page’s worth might barely make sense. I know you know these words, these images, because you’re my sister and you’ve had to eat what I eat and see what I see, like it or not (and I’m thankful that you’ve liked as much as you have). But what will some future culture make of these glyphs? Will it seem like reality or fiction? Is there any difference anymore? I love it here, I do, but sometimes it’s hard to breathe through this filter.”

http://patchworkearth.net/?p=26#more-26

Mike: Do you think the kids are just more comfortable with something referential, even if they’re not sure what it’s from? Our brains seem to be wired that way now Patrick and I were discussing the other day how we use this pop culture references as a filter, because we are so bombarded with information nowadays, that it’s a way to process it.

Gary: I absolutely agree it’s a way to process information. As a comic fan and especially a superhero fan, I hear the word mythology thrown around a lot in reference to a sort of “justification” of superheroes. And that’s fine. But what people forget is that these stories, myths, were intended to explain stuff a lot of the time or give a deeper meaning, or give perspective on a real event. Achilles vs. Hector or Odysseus in the Cyclops’ cave aren’t just about violence or battles, it’s about a real war the Greeks had with Troy, it’s about how brains can be used to overcome a physical disadvantage. Same kind of stuff today everywhere from Harry Potter books to shows like Dead Like Me, Carnivale, and movies like The Incredibles and Sin City.

And if a kid hears me talk about a Ferris Wheel they need to topple with a slingshot and the Wheel’s called “The Goliath” – and ten years from now they hear about David and Goliath and remember it, maybe they’ll get a little perspective, so yes, I do agree it’s a way to help filter information.