I start an essay for most every movie I see. Whether I actually finish the essay – or even make any headway on a thesis – is another matter entirely.

I start an essay for most every movie I see. Whether I actually finish the essay – or even make any headway on a thesis – is another matter entirely.

Today I’ll be the old man who runs out of candy at Halloween and starts handing out worthless crap that’s lying around the house. July was tiring, and the first weekend of August was exhausting, and in the absence of having something real to give you, you get this.

I’ll spare you the beginnings of an essay on George A. Romero’s Diary of the Dead, because the two paragraphs I wrote bear a striking resemblance to something written more than four years earlier, but everything else is fair game. Coherence, cogency, and complete sentences are neither promised nor implied.

Why bother?

For one thing, my Google Docs and hard drive are clogged with these fragments, and by publishing them I am freeing myself, turning my demons into angels.

Second, I think it’s really funny to see exactly how far I didn’t get in writing about Eastern Promises and Stranger Than Fiction, even though I have notes (with the former) and some recorded ramblings (with the latter) that would serve as ample raw material.

Third, maybe somebody wants an intimate look at my writing process. Not likely, but … .

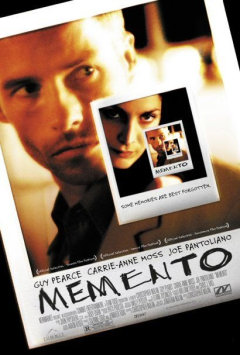

Fourth, maybe there’s an idea or reading that might interest somebody. The Memento piece is actually fairly substantial, although it’s missing context and connective tissue. (Update, 15 April 2009: Although I didn’t refer to or re-use the shards offered here when writing it, this is how the Memento piece would look in its finished form.)

So without further ado, here – in descending order of embarassment – are the offerings in the inaugural edition of “Shit That Didn’t Get Wrote.”

Eastern Promises

There is a feeling of disappointment that

[Yes, that’s it.]

Stranger Than Fiction

as rigorous as its circular paradox will allow

[Hey, it’s something.]

The Darjeeling Limited

Wes Anderson’s shtick has gotten old very quickly, and it’s his own damn fault.

Cure

The 1997 Japanese thriller Cure is like a fusion of the procedural and serial-killer elements of Se7en with the creepy atmospherics and supernatural motifs of The Ring, but with two-thirds of the explanation stripped away. I’m still not sure what happened at the end, whether two scenes on a bus were real or dreams, and if there was any connection between the movie’s “villain” and the mysterious Mesmer.

One might chalk this up to cultural differences, or perhaps the difficulty in absorbing relevant visual information when one’s trying to read subtitles, but I prefer to think that writer/director Kiyoshi Kurosawa is simply working more subtly than I’m used to; he’s making me work harder.

The Fountain

Darren Aronofsky loves failure, so it’s great to see that he fully committed to it in The Fountain.

Failure is such an obsession in Aronofsky’s work that he was bound to mimic his characters eventually, and with his third film the writer/director most resembles π’s Max Cohen – a driven, brilliantly talented man whose reach exceeds any person’s grasp. A modern Icarus.

[Insert thoughtful, convincing support here.]

The Fountain is gorgeous to watch and perceptive about the human need to triumph over death, but the movie is so conceptually blunt – three separate stories with 500 years between them, with the primary characters played by Hugh Jackman and Rachel Weisz, with Jackman on a quest to find immortality and/or defeat death – that there’s not much room for character, plot, or theme development.

Memento

Christopher Nolan’s Memento is legendary for the volume of time, energy, and words spent figuring it out and unlocking its puzzles, perhaps only rivaled in the past decade by David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive and Bryan Singer’s The Usual Suspects.

It’s a credit to Nolan’s movie, though, that it remains an enigma, with depth that hasn’t been explored much if at all. The movie requires so much attention and work to simply follow it – even after you’ve seen it once or twice or three times – that it’s difficult, though still rewarding, to delve a little deeper.

A couple of issues continue to fascinate me:

- how the movie’s form affects its meaning, and

- how Teddy becomes Leonard’s new wife.

I’ll deal with these separately. If you haven’t seen the movie, you won’t understand much if anything of this. If you have seen it, I’m not going to promise that you’ll fare much better.

The nagging suspicion of some viewers has been that Christopher Nolan’s Memento would amount to little if it didn’t employ its backwards structure. It’s a fair question to raise, but if you watch the movie chronologically (an option on the labyrinthian special-edition DVD), you’ll find that Memento holds together surprisingly well.

Most aspects of the movie have been discussed at length – the best one-stop shop is this analysis at Salon.com – but I have yet to see something that talks about how structure affects the meaning of Memento. (The Salon.com piece does, however, relate the plot in it chronological order, and that should be enough for people who haven’t seen the movie that way understand what I’m talking about.)

The story told linearly certainly has a different effect, but it’s still elegant and full. From chronological beginning to end (as opposed to the film’s terminals), the narrative involves memory-impaired Leonard’s decision to make Teddy his John G. – the path he takes to determining that Teddy was his wife’s killer and ultimately murdering him.

Re-assembled, the movie would begin with the first black-and-white section the audience sees and travel through those segments beginning to end, leading up to the murder of Natalie’s boyfriend Jimmy. (It is from this moment, when the picture of Jimmy’s dead body is developing, that the story is told in color.) From there, the rest of the movie would proceed from the last color scene (Teddy’s explanation of Leonard’s history, his affliction, and his behavior since the death of his wife) through the first (Teddy’s murder).

What you lose in this telling is the challenge of keeping up with the information you learn about Leonard, and trying to follow how the current scene leads up to the one you just saw. What’s left is a story about a confused and perhaps deluded person who creates “facts” out of interpretation and ends up making major lapses in judgment because of the information he’s missing. You’re also left with two secondary characters – Natalie and Teddy – who are playing Leonard toward uncertain ends. Teddy, in particular, seems to be helping Leonard, but his manipulation eventually leads to his death. It might not be the same as the movie that was made, but it’s still compelling.

[The next section is, to the best of my recollection, an adaptation of an e-mail conversation with Drunken Commentary Track collaborator Mike Schulz, dating from 2000. Yes, I’m giving you some dusty, musty crap.]

1) Sammy’s story is actually Leonard’s. (And the last time we see Sammy, in the hospital, some

body walked in front of him, and I would swear that I saw Leonard instead of Sammy after the person passed.) [Of course, this is obvious with repeated viewings. And note that Lenny Shelby has the same number of letters in each name as Sammy Jankis, and that Leonard doesn’t want to be called “Lenny.”] Leonard creates Sammy’s story as a way to distance himself from his complicity and his impotence; it’s a moral tale to him, one that advises him to keep organized notes and pursue a goal.

2) Leonard’s wife was raped and attacked by one person but survived, and Leonard lost his memory while trying to prevent/stop the attack.

3) Leonard killed his wife accidentally in the same way that Leonard claims Sammy killed his.

4) After his wife died, Leonard created a story in his mind that his wife was killed in the attack and that two men (instead of one) attacked her. He thus gives purpose to his life by giving himself a mission.

5) Leonard enlists Teddy to help him find the second attacker (John or Jimmy G). Teddy helps him locate his man, and Leonard kills him, but Teddy begins to doubt Leonard’s story when he realizes how Leonard twists things to suit his goal. (At the beginning of the narrative, Leonard has just killed “Jimmy” – at least his second murder of a person one can assume Leonard thinks was the second attacker.)

6) Leonard re-starts his quest every time he commits a murder. At the beginning of the story, he sets the score to zero and starts down the path that will lead him to murder Teddy. (He notes that Teddy will become his John G.)

7) Teddy seems to be playing with Leonard and at the same time trying to keep tabs on him.

8) Teddy becomes the wife of Leonard/Sammy – testing him to discover the origin of his “condition.” In that way, the story comes full circle: Just as Leonard’s wife died because she couldn’t believe that Leonard couldn’t snap out of it, so does Teddy die for making the same mistake – thinking that somehow Leonard was “faking” it, or that his condition was psychological rather than physical – which it arguably is, but stronger than Teddy and Leonard’s wife think.

[The remainder is, I’m fairly certain, the remainder of the e-mail that I never even began translating.]

What I would say is that Leonard’s condition is not purely physical, that it has some psychological component. I think that Leonard’s brain exploits the physical condition for its own end – namely, trying to make Leonard think that he had no role in his wife’s death. The mind, I would argue, takes Leonard’s post-injury story and transplants it to Sammy. Guilt is transferred, and Leonard now has a quest – to find his wife’s murderer.

Taking it even a step further, one could argue that Leonard’s note to himself – “Remember Sammy Jankis” – could have two purposes. The first to prompt Leonard why he must continue on his quest. The second as perhaps, somewhere down the line, a prompt that might jar Leonard into realizing the real story.

I like the idea of one sentence or even sentence fragment reactions to films (although I think you were a bit harsh on Eastern Promises and The Darjeeling Limited). You can attain a haiku-like elliptical style with a clipped, suggestive mystery. Here are some that come to mind:

In The Bank Job, Statham acts more than usual and his character’s married.

Charlie Bartlett steals from Rushmore to an uncomfortable degree.

A phrase for Pineapple Express: poor Rosie Perez

FDr: Agreed, although I think you mistook my comments on Eastern Promises (which I like very much) and The Darjeeling Limited (which I did not). They weren’t meant as concise summary; they were merely as far as I got.

(Trying out the “login as livejournal” function here…)

“Stranger than Fiction” was a very odd duck. There was a lot to dislike, but there’s one sequence that spoke to me particularly. My site’s full of works about the conflict between character and author, and in a lot of details the film was eerily like my own work, so I was rapt, perhaps more than it deserved. But when Ferrell’s character goes to Dustin Hoffman, and Hoffman tells him that he needs to die for the “masterpiece” to work, to Ferrell’s tears… and then he reads the script for his life on the bus and realizes that it’s true, the story deserves his tragic death… that’s a legitimately great moment, not supported by the story as a whole (which hadn’t done enough to earn the “masterpiece” that the plot revolved around).