The Spoiler’s Creed applies.

A Love Letter to The Wire

The 58th – and second-to-last – episode of The Wire, David Simon’s sociological HBO drama about Baltimore, is titled “Clarifications,” and one scene succinctly serves that purpose.

The 58th – and second-to-last – episode of The Wire, David Simon’s sociological HBO drama about Baltimore, is titled “Clarifications,” and one scene succinctly serves that purpose.

When McNulty takes his faked serial killer of homeless men to FBI profilers, they nail the detective’s character in a few sentences based on his “evidence”: The murderer, they say, is a high-functioning alcoholic who works in a bureaucracy and has a problem with authority. McNulty – in Dominic West’s performance, always lacking self-awareness – can barely cloak his petrified amusement. He seems to be thinking: Am I that easy?

The scene confirmed for me that the fifth season of the lauded show is a comedy. More crucially, it summarized The Wire’s outlook: It knows people, and believes that you can know them, too, with just a few clues. It has a storyteller’s belief in the telling detail, and the reporter’s faith that people are consistent, and reducible to a few key traits.

So you might be surprised by what happens to the characters, but you’ll rarely be surprised by what they do.  (The detective you’d expect to be played by Morgan Freeman is even named Freamon.) Their creator – a former reporter, naturally – has drawn them incisively and grounded them, but they’re not particularly complicated, and they’re unlikely to change.

(The detective you’d expect to be played by Morgan Freeman is even named Freamon.) Their creator – a former reporter, naturally – has drawn them incisively and grounded them, but they’re not particularly complicated, and they’re unlikely to change.

All those things can also be said about the institutions that are at the heart of The Wire. The show is built on an assumption of the corruption and the inertia and the inefficiency of bureaucracies and systems, and at virtually every opportunity it has argued through its convincing and compelling narrative that even well-meaning, sensible, and earnest efforts at reform will be rebuffed.

For example:

- Bunny Colvin tried to legalize drugs. Canned.

- Tommy Carcetti promised real change in the police department and meant it. A school crisis forces him to cut the cop shop to the bone.

- Stringer Bell tried to transform drug organizations into legitimate businesses. Dead.

- D’Angelo Barksdale questioned the rules of The Game. Dead.

- Prop Joe tried to civilize and unite drug dealers, for his benefit and theirs. Dead.

- Prez tried to teach kids something. He finally taught to the test.

- Gus has tried to maintain journalistic standards at the Sun. He’s continually overridden by Pulitzer-lusting execs, and his protests have become meek.

- McNulty found happiness and stability on foot patrol. He got sucked back into his boozing, philandering murder-police ways.

- Omar left Baltimore. He got sucked back into his role as the official nuisance of the drug lords. Also: dead.

In the wider view, the procedural conceit of the show – following one wiretap case each season – reinforces Simon’s central assertion that nothing ever improves for long, and only the players change. Barksdale is replaced by Marlo, Royce by Carcetti, one case by another … .

Only dope fiend Bubbles and ex-con Cutty seem to have genuinely changed for the better over the course of the series, and I don’t think it’s a coincidence that they’re the least institutionalized adults on The Wire. They can change because they’re not part of something bigger.

The show’s cynicism is so complete that it makes the act of quarantining all the addicts and drug dealers in one run-down neighborhood feel downright hopeful, and Simon is clear that in his view the city’s drug organizations are the least dysfunctional in the show – disciplined and inventive if brutal.

For all its strengths – and the claims of some that it’s the best thing ever broadcast on American television – The Wire is far from perfect. It is conceptually awkward, in the sense that the expansion of the narrative and sociological scope has rarely felt natural.  Season two’s labor-union plot remains an entertaining but incongruous trifle and is perhaps best seen as a preemptive response to inevitable charges of racism. (See, here are some dumb-ass white folks that make these drug dealers look damned smart.) The deus ex machina that drove Prez – and consequently the show – into the schools wouldn’t have leaped out on a lesser series, but on The Wire it’s a sore thumb. And Simon and company didn’t even bother in season five with an elegant segue into the media; the reporters and editors just show up independent of existing storylines.

Season two’s labor-union plot remains an entertaining but incongruous trifle and is perhaps best seen as a preemptive response to inevitable charges of racism. (See, here are some dumb-ass white folks that make these drug dealers look damned smart.) The deus ex machina that drove Prez – and consequently the show – into the schools wouldn’t have leaped out on a lesser series, but on The Wire it’s a sore thumb. And Simon and company didn’t even bother in season five with an elegant segue into the media; the reporters and editors just show up independent of existing storylines.

They’re minor complaints, but significant because they suggest a lack of rigor in the show’s architecture. Outside of being about Baltimore’s inner city, the show has no consistent focus. It expands and contracts with its creator’s wandering aim, and as a result it’s more than a touch messy.

Yet within each season the show knows exactly what it wants to be and what it wants to say, and there’s a tone to each case, and an overall arc. The straightforward police work of the first two seasons (essentially describing the problems of institutions) led to ideas and optimism (Hamsterdam, the drug trade stripped of barbarism, and a “new day in Baltimore”), which were later offset by grim realities epitomized by contemporary inner-city education. The overarching message is that these problems are bigger than any person’s desire and ability to change them. The status quo will win.

Although it has that same fundamental theme, the fifth season feels quite different: It’s heavy-handed and borderline absurd. The silliness of McNulty’s made-up serial killer. The brazenness of Templeton’s fraud. The convolutions involved in tying McNulty’s case to Lester’s. The sycophantic, one-dimensional newspaper executives. The almost startling ease with which Sydnor cracks Marlo’s code once the writers put him in a car with a map book and get him lost. The cameos by ghosts of seasons past, most surprisingly Nick Sobotka. The hilariously outsize vanity of Carcetti, getting off on the sexiness of his own indignation. It’s almost as if Simon is cashing in all the authenticity chips he earned over the first four seasons.

Even the death of Omar is given a comic twist, as the most feared man on the Baltimore streets gets cut down to size – his pockets rifled through, denied even a few words in the newspaper, and tagged incorrectly at the medical examiner’s office, after being shot not by his enemy but by some punk-ass kid. In life, he was huge, even in his absence; in death, he’s officially nothing, even as his legend grows.

Even the death of Omar is given a comic twist, as the most feared man on the Baltimore streets gets cut down to size – his pockets rifled through, denied even a few words in the newspaper, and tagged incorrectly at the medical examiner’s office, after being shot not by his enemy but by some punk-ass kid. In life, he was huge, even in his absence; in death, he’s officially nothing, even as his legend grows.

The pleasant shock is that The Wire’s swan-song-season ridiculousness isn’t a function of frustration and anger. There’s a lightness here, a warmth, in how Simon and his writers are working in old friends, and while these efforts are rarely natural, I can’t complain a

bout getting to say goodbye to Bunny, and seeing that Namond turned out well under his tutelage. (Bunny, thwarted in Hamsterdam and the schools, succeeds on an individual level. There is hope.) Despite his bleak outlook – and there’s no doubt that the finale will restore the power of the institution over its rogue elements – Simon wants to leave his audience happy.

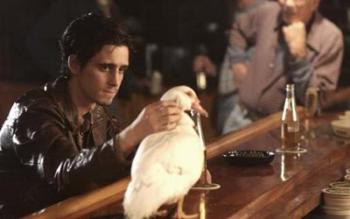

And to be fair, there’s always been a whiff of the ludicrous in The Wire, and I don’t know that McNulty’s fabricated murderer is any less likely than Hamsterdam, or Ziggy’s duck, or the imposition of Robert’s Rules of Order on street-level drug peddlers, or the bottomless stupidity of Herc … .

And to be fair, there’s always been a whiff of the ludicrous in The Wire, and I don’t know that McNulty’s fabricated murderer is any less likely than Hamsterdam, or Ziggy’s duck, or the imposition of Robert’s Rules of Order on street-level drug peddlers, or the bottomless stupidity of Herc … .

Yet that aspect of the show is amplified in these final 10 episodes, just as this condensed season feels rushed. Things that might have developed over several episodes in past years pay off more quickly – but with less satisfaction – now.

That contributes an urgency to the show, I suppose, and is perhaps a reflection of its band of increasingly careless renegades: McNulty, Freamon, Templeton, Omar … . We know the fate of one of these characters already, and the smart money says that only Templeton might emerge with something approaching his previous status intact. He is, after all, the only one subverting the system with the full (albeit ignorant) blessing of authority.

But The Wire is not about human beings. It’s a show of themes and rhymes relating to cycles, about the immutability and inevitability of outcomes within systems. Like its beloved HBO brethren Deadwood and The Sopranos, The Wire is a rich, detailed, intricate, smartly written, colorfully spoken, vividly populated show that revitalizes a tired formula and has more to say about culture and community than about actual people.  Countless characters live in my memory – from the marble-mouthed, androgynous Snoop to the gleefully corrupt Clay Davis to the quietly commanding, beret-ed Vondas to uptight Daniels and his riveting, cold cadences – but they serve at the pleasure of the larger goal.

Countless characters live in my memory – from the marble-mouthed, androgynous Snoop to the gleefully corrupt Clay Davis to the quietly commanding, beret-ed Vondas to uptight Daniels and his riveting, cold cadences – but they serve at the pleasure of the larger goal.

Among these three great David shows, I think Deadwood was the best front to back and top to bottom and side to side, and The Sopranos obviously captured the cultural imagination and paved the way for the other two. (Yes, those are backhanded compliments to Mr. Chase.)

But I was happy to see The Sopranos go. (I would have been happier for it to go sooner and more quickly.) And while I would have loved more Deadwood, it feels complete enough, even in its aborted state.

The Wire is the only one I’ll miss. I expect to cry a little at the end of Sunday’s finale – not for what happens to anybody, but because it’s over.

Omar had to die–you can’t be a lasting legend and grow old gracefully.

“Only dope fiend Bubbles and ex-con Cutty seem to have genuinely changed for the better over the course of the series, and I don’t think it’s a coincidence that they’re the least institutionalized adults on The Wire. They can change because they’re not part of something bigger.”

I’d argue that Carver changes for the better over the course of the series, and the reasons for his growth have everything to do with his being part of something bigger.

Some further comments:

1) Through five seasons less the finale (something like 60 hours worth), I believe we’ve seen only two instances where an officer discharged his weapon — Pryzbylewski accidentally shooting into a basement wall in season one, and then his inadvertent killing of another cop in season three. Is that correct?

2) I’m always amazed at the low opinion many fans and pundits have of season two. In my opinion the Sobotka story line was where The Wire went from being really good to being great. Frank’s Dead Man Walking scene to end the penultimate episode rivals anything from The Sopranos or the Godfather films.

3) Has any network at any time had three dramas running concurrently that were as great as The Sopranos, Deadwood, and The Wire? I sincerely doubt it. It wouldn’t surprise me if twenty years from now people look back on the last nine years as being the second golden age of television, all because of those three HBO titles.

Joe:

I’d agree that Carver has changed for the better, and I’d also argue that it won’t stick – even though we won’t know that by the end of Sunday’s episode.

1) I’m not sure, but it sounds right, and it’s a good point.

2) I liked the second season very much; I just don’t think it fits.

3) I doubt it, too, and I agree completely.

I should be clearer about my comment that “The Wire is not about human beings.”

1) Of course it is. It’s a television series that features people.

2) Of course it isn’t. They’re characters, not human beings.

3) My point was that fundamentally, the show is more about the institutions than the characters/people. I think the finale bears this out, as Simon makes explicit that there’s a new McNulty, a new Omar, a new Bubbles, a new Daniels … . These are, of course, “human beings,” but their roles are important, not their individuality.

“Omar had to die–you can’t be a lasting legend and grow old gracefully.”

Not necessarily true. Google “Melvin Williams” the actor who played Deacon on the Wire. He’s a legend of the real Baltimore drug trade and he’s growing old gracefully.