T.R.A.N.S.I.T.

The animated T.R.A.N.S.I.T. is a feature-film plot distilled into 10 minutes, and it shows the ways in which the short film is more forgiving than longer cinematic forms. This movie operates wordlessly almost as a plot outline, and it’s gorgeous to look at and challenging to keep up with. It feels like a small, perfectly cut gem.

The animated T.R.A.N.S.I.T. is a feature-film plot distilled into 10 minutes, and it shows the ways in which the short film is more forgiving than longer cinematic forms. This movie operates wordlessly almost as a plot outline, and it’s gorgeous to look at and challenging to keep up with. It feels like a small, perfectly cut gem.

On reflection, that’s a good analogy, because Piet Kroon’s 1997 short is a beautiful piece of visual craftsmanship that fails as art in any rational analysis.

The movie opens with a suitcase floating on the water, decorated with stickers representing its travels. Like Memento’s core narrative, T.R.A.N.S.I.T.’s individual scenes move forward in time, even as their placement moves the story backward. (Scene B follows Scene A in movie sequence, but it begins and ends before Scene A in plot chronology.)

The film uses the suitcase as the source of its transitions, as if this inanimate object were remembering that time in the Hotel Baden-baden that its owner slathered the buff young man with strawberries while her husband slept in another room … . But I’m getting ahead of myself. Or behind myself.

The film uses the suitcase as the source of its transitions, as if this inanimate object were remembering that time in the Hotel Baden-baden that its owner slathered the buff young man with strawberries while her husband slept in another room … . But I’m getting ahead of myself. Or behind myself.

The first stop is a cruise ship, and Kroon swoops around and above the massive boat, and finally dives through its hull, to the belly where coal is being shoveled into a fire. We travel up the smokestack to the deck, and see wealthy, elongated people at rest and play. Something ugly powers all this pleasure … .

A man emerges from inside the ship, carrying the suitcase, his arm in a sling. He throws the luggage overboard, into the ocean.

What’s in the suitcase? Well, in the next scene, a woman is on a train, doing her own disposal, tossing a gun out the window. In the next scene, she’s beaten and bruised, lying naked on a bed with that same muscled man. Hmmm … .

What’s in the suitcase? Well, in the next scene, a woman is on a train, doing her own disposal, tossing a gun out the window. In the next scene, she’s beaten and bruised, lying naked on a bed with that same muscled man. Hmmm … .

Highly stylized, playful, and gorgeously, evocatively, elliptically rendered (in an Art Deco style), T.R.A.N.S.I.T. visually is a fizzy joy.

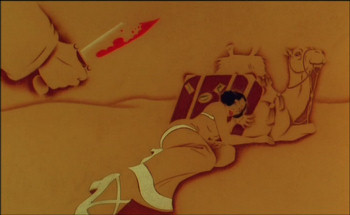

Different animators worked on different scenes, and as a result each has a distinct expressive aesthetic, matching the look with the locale and tone of the scene. Blues, purples, and blacks dominate a nighttime episode on the Orient Express, with the mood broken by bloody reds. A casino sex scene is hazy, as if desire fogged the details, and the bodies nearly glow. You can feel baked Cairo.

But the eye candy is all empty calories. The backwards structure is not justified by the content (unlike with Memento), and it’s difficult to follow not because it’s complicated, but because your attention wanders; on a plot level, it’s pedestrian and dull, yet it’s so fractured and brisk that you expend a great deal of brainpower keeping pace – with little reward. The yearning score regularly swells, and we see jealousy, violence, sex, and death, but there’s no investment in the characters or their actions, because we don’t have any sense of them beyond their appearances. Your only allegiance is to the look.

But the eye candy is all empty calories. The backwards structure is not justified by the content (unlike with Memento), and it’s difficult to follow not because it’s complicated, but because your attention wanders; on a plot level, it’s pedestrian and dull, yet it’s so fractured and brisk that you expend a great deal of brainpower keeping pace – with little reward. The yearning score regularly swells, and we see jealousy, violence, sex, and death, but there’s no investment in the characters or their actions, because we don’t have any sense of them beyond their appearances. Your only allegiance is to the look.

There’s an argument, I suppose, that this story is so universal that it doesn’t require specifics. Why, then, is there epilogue text explaining, dumbly, that “Emmy Buckingham Parker was last seen boarding the Orient Express in Venice in October 1928”? Why tell the story at all if it exists merely as a framework on which to hang pretty pictures? Why, at the film’s end, do we see the young man, in a bloody apron, with his children and pregnant wife – all of whom he’s about to leave for an elegant woman who flirted briefly with him?

In short films, every moment and detail is precious, so Kroon would seem to be saying something along the lines of “Once a butcher, always a butcher.” Or: “Chopping up dead animals supports a family better than chopping up lovers.” Or: “Don’t follow your dick.” Most likely, the filmmaker has nothing at all to say.

Ignore T.R.A.N.S.I.T. as a narrative. Pretend the plot doesn’t exist. Luxuriate, instead, in its string of associative images

(If YouTube irritates you, T.R.A.N.S.I.T. is available on the collection Short 4: Seduction.)

(This essay is a contribution to the Short-Film Week blog-a-thon.)

TRANSIT is one of best shorts I ever seen. Piet Kroon and Ian Harvey are together in a new movie: “Not the End of the World”!

The movie production company: http://www.illuminatedfilms.com

Bye,

Alex

“Don’t follow your dick.”

I suppose there are many ways to interpret what we’ve just seen in TRANSIT. I suppose I find it a little odd he wouldn’t want to come back to his family in the end, given the way the film chose to give him a name and further epilogue too. Of course I thought he was a young man, perhaps the son of a butcher who works at his shop, but I suppose that’s wishful thinking, he was going to be dead in 30 years, but now I just spoiled that of you guy unsuspecting readers!