Contact

Robert Zemeckis’ Contact is a triumph of short-form – .

Robert Zemeckis’ Contact is a triumph of short-form – .

What’s that?

Yes, I’m aware that Contact isn’t exactly short, but the Screen Actors Guild defines a feature film as a movie of 80 minutes or longer, and Contact’s 53-minute running – .

Pardon me?

Yes, I know that Contact was 150 minutes long when it played in movie theaters. I’m not talking about that movie. It was terrible and interminable.

My version uses the same source material but starts at the 33-minute, 25-second mark and ends at one hour, 26 minutes, and five seconds. It’s a marvel of economy and – .

Yes, as a matter of fact I do think you can chop off the first half-hour and the last hour of the theatrical version without losing – .

What? You liked all that backstory and preface? You thought it was necessary? And you were satisfied with the way the movie dragged on, and ended &mdash and then ended again?

Now shut up and let me explain myself.

Godard supposedly said that the best way to criticize a movie is to make another, so I am exposing the bankruptcy of the theatrical version of Contact with my superior edit. That my cut is 63 percent shorter is gravy.

Let me start by showing that Zemeckis himself perhaps had an inkling of my Contact. Our movie starts with Ellie (Jodie Foster) getting out of her car, obviously upset, and she sits and hugs her knees. The beginning:

The shot continues:

Our movie ends with a shot of Ellie in a hotel room, obviously upset, and hugging her knees. She has no vehicle this time; the transport for which she yearned has been given to somebody else:

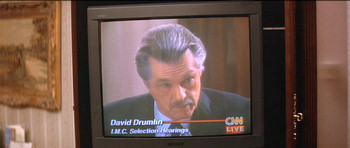

Oh, that’s not all. She’s even wearing a similar sweater. And the parallels continue, in the way that the opening shot is followed by spiritual leader Palmer Joss (Matthew McConaughey) on CNN, and the closing shot is preceded by David Drumlin (Tom Skerritt) – Ellie’s patronizing professional rival – on CNN:

Both men are rebuking her allegiance to science, and her refusal to acknowledge God – indirectly in the first case, and more pointedly in the latter.

The level of symmetry is uncanny, and is perhaps a key or primer to unlock the movie – a concept invoked by the film itself as Ellie and other scientists try to understand what exactly has been sent to them embedded in pulses of prime numbers and amplified images of Hitler opening the 1936 Olympics in Berlin.

My version of Contact is undoubtedly abrupt and brisk, and many people will find it baffling. It’s an hour-long character drama dressed up as a thriller that promises epic science fiction and metaphysical truths and delivers neither. The alien signal and construction project drive the plot but are finally irrelevant; they’re not quite MacGuffins, but they’re not quite important, either.

This clipped edition of Contact is about the education of Ellie, how her ideals are challenged and her project is threatened by forces military (personified by James Woods’ character), spiritual (McConaughey), and political (Skerritt). It doesn’t have a happy ending, as national security takes precedence over scientific inquiry, and as Ellie’s candidacy to possibly travel to other worlds is torpedoed by a question about faith, her agnostic answer to a selection panel, and Drumlin’s pandering response to that same committee. She doesn’t get what she wants, but she’s wiser. My movie begins in literal near-darkness (twilight, ignorance) and ends in the full, bright, artificial light of a hotel room (knowledge, of a sort).

And even though Joss and Drumlin act selfishly in the climactic interview process, they both raise legitimate arguments against Ellie’s participation. The audience and the movie root for Ellie, but we must also recognize that there are valid reasons that she shouldn’t be picked. That prevents my ending from seeming cynical; in the end, the right choice is probably made.

The short Contact, then, clarifies the themes of the material through subtraction – it doesn’t bog them down in new-age bullshit, Daddy issues, terrorist subplots, and sheer girth. The attention paid to Jake Busey’s wild-eyed religious zealot becomes somewhat problematic, but it can be justified; his character is an acknowledgment that science can be seen as a threat to religious faith, and his cold stare demonstrates that religious faith can also be perceived (by Ellie, in this case) as a threat to science. That’s one example in this version of the movie of an idea being introduced elegantly and given room to breathe and grow in the viewer’s mind, and there are plenty more.

Generally speaking, my Contact is brutally efficient in the delivery of narrative, thematic, and connective information. In its opening minutes, there’s Palmer Joss, establishing – in his comments to Larry King – the importance of spirituality. There’s a shot from space that subtly offers Ellie’s primary concern – What’s out there? – while gracefully presenting the incoming alien signal, contrasting it with the broadcasting of CNN. Palmer serves as a transition to Ellie’s lab, as her cohorts are carving a pumpkin at work while Joss’ interview plays on TV.

Generally speaking, my Contact is brutally efficient in the delivery of narrative, thematic, and connective information. In its opening minutes, there’s Palmer Joss, establishing – in his comments to Larry King – the importance of spirituality. There’s a shot from space that subtly offers Ellie’s primary concern – What’s out there? – while gracefully presenting the incoming alien signal, contrasting it with the broadcasting of CNN. Palmer serves as a transition to Ellie’s lab, as her cohorts are carving a pumpkin at work while Joss’ interview plays on TV.

When he shows up an important cabinet meeting later in the movie, Ellie’s expression and the way he looks at her tell you all you need to know about their romantic history; this movie is elliptical where the theatrical version was blunt. The audience has to work to keep up, but I have no doubt that most folks have a sense of the previous conflicts between, for example, Ellie and Drumlin without actually seeing them; filmmakers should trust their casts to convey that past nonverbally.

And then there’s Ellie’s biography, which is delivered – in a casual display of power and resources – by mysterious financier S.R. Hadden. The audience makes the astonishing leap that orphaned girls have some healing to do.

Of course, it’s impossible to see my Contact fresh; it will always have the context of the bloated original, making it difficult to evaluate this lean, mean version on its own. And I’m certain that the final shot doesn’t play quite right, because it’s not held long enough. (We end right before Palmer knocks on the door.)

But whatever its narrative shortcomings, it’s truer to the themes and ideas of Contact, and to experience. It finds a small, human honesty instead of an unattainable – and impossible to show or prove – universal Truth.

But whatever its narrative shortcomings, it’s truer to the themes and ideas of Contact, and to experience. It finds a small, human honesty instead of an unattainable – and impossible to show or prove – universal Truth.

It’s a story about a quest, not about completing it. When the questions are as existential as those posed in Contact, how could there possibly be anything approaching a satisfying resolution? Do we ever conclude our search for God or meaning or purpose?

And even if such elusive knowledge were possible, it’s often a dead end – as Zemeckis so turgidly proved.

(This essay is a contribution to the Short-Film Week blog-a-thon.)

Nice work, and a very good idea. I usually have little tolerance for Zemeckis, but you’ve made me want to see at least the portion of the film that you’re talking about here — it sounds like it would be the best film he ever made.

i disagree…

http://video.google.co.uk/videoplay?docid=-3331561910734827921

Anonymous: You disagree with what?