(A contribution to The House Next Door’s Close-Up Blog-a-thon.)

Crowding Keitel in “Smoke”

The movie begins in Auggie Wren’s cigar shop with omniscient chatter about the Mets and ends in a deli with a made-up tale about how Auggie got his first camera. Almost everything in between is also bullshit, in the sense that its relationship with objective reality is utilitarian. We speak the truth when it suits our needs, but we shouldn’t let it get in the way of the story we’re trying to spin.

The movie begins in Auggie Wren’s cigar shop with omniscient chatter about the Mets and ends in a deli with a made-up tale about how Auggie got his first camera. Almost everything in between is also bullshit, in the sense that its relationship with objective reality is utilitarian. We speak the truth when it suits our needs, but we shouldn’t let it get in the way of the story we’re trying to spin.

Smoke, the 1995 collaboration between director Wayne Wang and author Paul Auster, isn’t judgmental about lies and half-truths. It pays respect to and finds value in narratives of all sorts, from an anecdote about Queen Elizabeth and Sir Walter Raleigh and the weight of smoke to the construction of identity through fibs.

But that doesn’t really become clear until the deli scene, in which Auggie tells about how he had Christmas dinner with the blind grandma of a kid who shoplifted from his store and ended up taking a brand-new camera from her apartment. Auggie’s audience, a novelist named Paul Benjamin, gently summarizes the movie:

“Bullshit is a real talent, Auggie. To make up a good story, a person has to know how to push all the right buttons. I’d say you’re up there among the masters.”

“What do you mean?”

“It’s a good story.”

It is a good story. And Smoke won’t let you forget it.

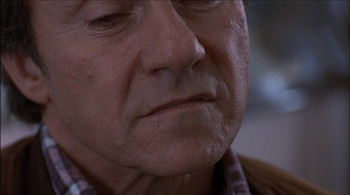

The story is told (by Harvey Keitel) in a single take, in a shot that starts framing the two men from over Paul’s shoulder and slowly encroaches on Auggie’s personal space, ending up framing his mouth. Length: a few seconds shy of five minutes.

It is a striking shot, for three reasons.

First, the gradualness of the zoom is subtle enough that’s is nearly imperceptible in the moment. The viewer only notices the tightening frame in retrospect, in remembering how the shot looked different some seconds ago.

Second is the performance by Harvey Keitel. The actor gives the movie much of its worn, warm charm, and in this monologue walks the character’s line between being kind and being a minor crook. The telling is devoid of pride or shame, but there is emotion in it, as the performer seems to measure every word, secretly relishing it.

Third, the visual treatment of the storytelling would appear to be a function of choices on the set and in the editing room rather than an approach from the outset. In the final script, there’s no mention of the gradual close-up, and images of Keitel telling the tale were intended to be intercut with the scene being described. (Those images now run under the end credits.)

The goals of the shot that ended up in the movie are obvious: The single take underscores the power of oral narrative by refusing to cut away, while the camera is a surrogate member of the audience, drawn in by the account and inching closer to make sure that it doesn’t miss the littlest detail.

But as low-key as the shot is, it’s still overbearing.

Look at where the shot begins and where it ends. Would it be any less effective at conveying its information if it stopped short of giving Keitel an oral exam?

More importantly, the subtle showiness of the shot works against its thesis that this is great storytelling. The premise of this scene is that you don’t need to see the action of the narrative on the screen to be enraptured by it; Wang and Auster appear to be arguing against filmed stories, claiming that they’re unnecessarily adorned by bling such as acting and visual representation. It’s a good story, they seem to be saying. What more do you need?

The reality is, though, that the camera isn’t following the audience into Harvey’s mouth but leading it there; it’s telegraphing the intended effect, telling you how to feel – which Keitel and the story itself refuse to do. If the tale does its job, the shift from medium shot to close-up wouldn’t be necessary at all.

A static shot with one take would have better supported what the filmmakers were obviously after. The shot would stay the same, but you might lean a little closer to the screen.