(I haven’t written a word about baseball all year, so for the Totally Unrelated Blog-a-thon, here’s a mediation on the curious phenomenon that is my relative dearth of excitement and joy at the World Series win by the Boston Red Sox, my baseball team for the past 22 seasons. Bonus unrelatedness: plenty of digressions!)

The morning after the Red Sox won the 2007 World Series (following two miserable seasons of championship drought), two people approached me in McDonald’s. I was wearing a Red Sox shirt. We were in northern Arkansas, beginning an 11-hour drive north after a weekend of wedding festivities. Incidentally, I eat at McDonald’s about as often as the Red Sox win the World Series.

The morning after the Red Sox won the 2007 World Series (following two miserable seasons of championship drought), two people approached me in McDonald’s. I was wearing a Red Sox shirt. We were in northern Arkansas, beginning an 11-hour drive north after a weekend of wedding festivities. Incidentally, I eat at McDonald’s about as often as the Red Sox win the World Series.

One person wanted to know how Game 4 had come out. (Very well, thank you.) The other marveled at seeing another Red Sox fan in Arkansas. (Just visiting.)

I should have been giddy on Monday morning, of course. Since the God-Damned, Motherfucking Yankees won four of five World Series between 1996 and 2000, only the Red Sox have collected two titles in baseball. And unlike in 2004 – when there was an urgency to the quest because of impending free agents and players obviously in decline – the team now appears built for longevity. The combination of young, farm-raised talent at the Major League level, analysis-based drafting, and deep pockets could make the Sox a title contender for the next decade or longer.

So if you haven’t learned to hate us yet – the way we invade your cities, drink your locally brewed beer (that’s me, by the way), and generally annoy you – wait a few years.

But my feelings the day after were muted, as I had a sense they would be. I smiled and chatted with the people who talked to me, but it didn’t feel like my team had just won the World Series.

There are lots of explanations, as a fan and as an individual. Nothing could compare to 2004. Not having to go through the God-Damned, Motherfucking Yankees in the postseason. Impending fatherhood. A conscientious effort to manage stress and blood pressure by not getting so worked up. The understanding that the long-term management of consistently winning franchises is ruthless and systemic, not some juju in opposition to a nonexistent curse. Being three years older. Not actually seeing more than a half-inning of the clinching game. (Thank you, Arkansas liquor laws, forcing taverns to close at 10 p.m. on Sundays. Bride of Culture Snob and I shared some earbuds and the portable XM radio while sitting in a hot tub for the final three outs. Poor us, I know.)

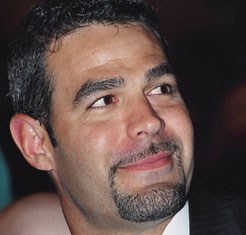

To be clear, I love the Red Sox no less. For the past two seasons, we’ve had nearly every game on in the house, even if we weren’t actually listening or watching. My casual wardrobe is still dominated by Red Sox T-shirts. We still fly the Red Sox flag from April through the end of the season, in Cubs country. Bride of Culture Snob got her first Red Sox T-shirt for her birthday this year, declaring a prescient admiration of Mike Lowell. (She thinks he’s cute, although the attention he pays to upper-lip facial hair bugs her a little.)

To be clear, I love the Red Sox no less. For the past two seasons, we’ve had nearly every game on in the house, even if we weren’t actually listening or watching. My casual wardrobe is still dominated by Red Sox T-shirts. We still fly the Red Sox flag from April through the end of the season, in Cubs country. Bride of Culture Snob got her first Red Sox T-shirt for her birthday this year, declaring a prescient admiration of Mike Lowell. (She thinks he’s cute, although the attention he pays to upper-lip facial hair bugs her a little.)

If forced to choose, I probably prefer this year’s version of the team over 2004’s. I’ll take Papelbon and the bullpen rhythm section over Foulke and his fellow relievers, 2007 Beckett over 2004 Pedro, Lowell over Mueller, Pedroia over Bellhorn, Matsuzaka over Lowe, and Youkilis over Millar. Hell, I even like Julio Lugo more than the three-headed monster that manned shortstop back then, and while the price is steep, the incomparably maddening J.D. Drew gave the Sox better production in right field than the 2004 combination of Kapler and Nixon.

The 2007 editions of David Ortiz and Tim Wakefield were substantially similar to their younger selves, and while the current versions of Schilling, Ramirez, and Varitek are obviously on the wrong side of the hill, their diminished value didn’t significantly hurt the team. Bobby Kielty equals Dave Roberts.

Edge to 2004: Arroyo over Tavarez, Damon over Crisp.

By virtually any performance measure, this year’s squad was better. It had scored 210 more runs than its opponents, compared to a 181-run differential in 2004. Using the basic Pythagorean formula for baseball, the 2007 Red Sox should have won 63.5 percent of their games, while the 2004 version should have won 60.4 percent. Yes, the 2004 team actually won two more games during the regular season, but we can chalk that up to Eric Gagne. (I was in Camden Yards for both of those games, you asshole. One inning pitched, 4 hits, 1 home run, 5 earned runs, 1 walk, 1 inherited runner allowed to score, one blown save.)

The 2004 squad had one distinct cultural-consciousness advantage: a carefree, goofy personality that, when combined with the team’s perennial-underdog status, made the Red Sox genuinely endearing.

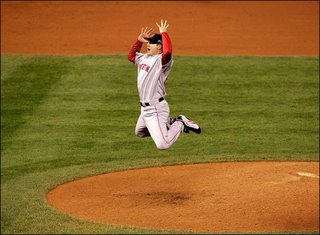

But that character wore thin even for this fan in 2004, and these Major League champions are (Papelbon’s now-tired jigging excepted) refreshingly professional – smartly wearing goggles when popping and spraying champagne, so that nobody loses an eye.

But that character wore thin even for this fan in 2004, and these Major League champions are (Papelbon’s now-tired jigging excepted) refreshingly professional – smartly wearing goggles when popping and spraying champagne, so that nobody loses an eye.

What’s changed is that the Red Sox now carry with them the expectation of success. They’re no longer the Almost-Weres, the team that will find some way to lose on the cusp of ultimate victory. Aaron Boone wrote the last words in that book in 2003, even though we didn’t know it at the time.

But if you follow baseball, you’ve been reading all about that in the past few days, how the Red Sox’s sweep of the Colorado Rockies means that 2004 wasn’t some fluke. (Even though it was, of course, as the Red Sox remain the only team in the long history of Major League Baseball to win a seven-game series in which they trailed three games to none.)

The realization that surprised me was that the expectation extends to the fans. I had a sense of that as soon as the playoffs began, and it was particularly acute when Boston trailed Cleveland three games to one in the American League Championship Series.

I didn’t feel like a Sox victory was guaranteed, or even likely. (On October 17, Baseball Prospectus put the Red Sox’s chances of winning that series at 13.2 percent, based on a million trials.) And defeat wasn’t imminent, either. I was amazingly calm.

Oddly, the expectation of sports success didn’t mean that a loss would be crushing. How can you get too agitated about a team’s poor performance in a short series after all it had accomplished over the 162-game regular season? Everybody should be aware of the dangers of small sample sizes, and that in baseball players and teams go through stretches of games when they can’t hit a ball out of the infield off a tee. J.D. Drew seemingly went through months when he was a ground-ball drill for second basemen.

Would a loss have hurt? Sure.

But if my team had lost one more game to Cleveland, there would always be next year. And when your team is run well, that’s not an empty hope.

The downside is that it makes victory feel almost routine.