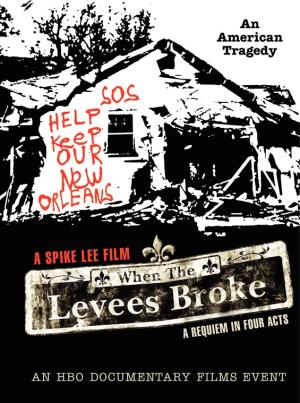

When the Levees Broke

The grief in Spike Lee’s When the Levees Broke is heartbreaking. Unfortunately, the anger in it is misinformed, facile, naïve, misplaced, unfair, inconsistent, unsupported, or some combination of the seven.

The grief in Spike Lee’s When the Levees Broke is heartbreaking. Unfortunately, the anger in it is misinformed, facile, naïve, misplaced, unfair, inconsistent, unsupported, or some combination of the seven.

To be clear, I do not begrudge the people of New Orleans for being pissed off at their municipal, state, and federal governments for their preparations for and responses to Hurricane Katrina, levee breaches, and flooding. When you’ve been through what they’ve been through, you’re entitled to your ire.

I do begrudge Lee, who had an opportunity to create either a poetic expression of loss, sadness, and fury or the definitive popular political document on the hurricane and its aftermath. Instead, he made something in between, a scattershot, muddled, formless four-hour documentary that is rarely illuminating and too infrequently poignant. It’s not just disappointing; it’s maddening.

The subtitle of the work is “A Requiem in Four Acts,” which suggests a coherent narrative or thematic groupings, none of which I discerned. If there’s an organizing principle to When the Levees Broke beyond breaking it up into four one-hour parts, I’d love to know what it is.

The familiarity of the core story apparently gave Lee license to dispense with basic context and story, and the lack of structure is symptomatic of an absence of point of view. Lee doesn’t appear to have anything to add to the voices of When the Levees Broke, so he just lets people talk.

And that’s a perfectly valid approach. It’s honorable and even noble to give a platform to the helpless and the wronged. Fresh pain and loss are powerful, and Lee’s documentary could have stopped at that and been a modest contribution to the record of Katrina, a work to make its devastation permanently immediate and personal.

But it doesn’t stop there, and allows many of its subjects to articulate deeply held beliefs and speculation that most people would find incredible.

There’s a jaw-dropping moment, for example, when it’s suggested that somebody set off explosives at certain locations on the levee to flood poor parts of New Orleans while saving richer neighborhoods.

The most interesting thing here (to me) is not that some people believe this, or whether it’s true or even possible. What’s fascinating is why people believe it. Disenfranchisement breeds conspiracy theories, such as the idea that the United States government created AIDS to decimate the black population – something that 15 percent of African Americans believe.

Other people might want Lee to evaluate the claim itself, to find out what evidence supports or undermines the allegation.

Both sides are likely to be disappointed. The famously direct filmmaker is wishy-washy here. He’s not advocating these points of view; he’s not subjecting them to factual scrutiny; and he’s not standing back as a sociologist, exploring the phenomenon rather than assertion.

Both sides are likely to be disappointed. The famously direct filmmaker is wishy-washy here. He’s not advocating these points of view; he’s not subjecting them to factual scrutiny; and he’s not standing back as a sociologist, exploring the phenomenon rather than assertion.

I read a distance between what people say and what Lee expects his audience to believe, but that’s inferred from the lack of argument either way. Unlike Michael Moore, who has the courage to stand in front of the camera and take responsibility for what he’s created, Lee is curiously silent, never seen and only occasionally heard asking a question.

When the Levees Broke often begs for his intelligent, outsider perspective, because people – particularly people under great stress – are a mess of twisted logic.

One example: The point is made forcefully that flooding, not the hurricane itself, was responsible for most of the damage to New Orleans; the argument goes that a better levee system would have spared the city. Yet when it comes time for people to bitch about their insurance companies, citizens are incredulous that their claims were denied because they didn’t have flood insurance.

So when it’s convenient for people to believe that this disaster could have been prevented through a better levee system, that’s what people believe. But when they need the hurricane to be responsible – so that they can collect insurance money – that’s what they believe.

Again, I’m not faulting New Orleans citizens, and I’m not claiming that insurance companies are blameless. But Lee never acknowledges the contradiction, never presents it in a context that might inform it. That’s certainly a challenge, because to dwell on the issue – or to debunk ideas about bombed levees – could discredit or cast as foolish the very people Lee obviously wants to support.

But there are ways to approach these things sensitively, and it starts with curiosity, genuine engagement, and pointed questions.

This is a matter of empathy, not credibility, and even if the audience dismisses some of the wilder assertions, it’s still critical to understand how they took root. People believe this shit because they’ve learned that society and their governments consider them disposable, and they come to the conclusion that powerful people would facilitate their deaths to save the homes of some rich white folks.

That’s the unspoken context of When the Levees Broke, but Spike Lee seems satisfied with sympathy.

You are correct. Levees were not bombed during or after Katrina. The reason why some people believe it was bombed, was because that actually happened to that same neighborhood in 1927 – levee cut with explosives during a flood because of the belief that sacrificing that neighborhood would save a more affluent part of the city. And, when the lower ninth levee failed before katrina’s arrival, it very quickly moved hundreds of feet crushing homes in its path and I am sure it made a lot of noise – like a bomb.

And, please recognize that our flooding was the result of catostrophic structural failure of many levees at storm surge levels well below for that which they were designed – they fell down without even being overtopped. Please understand these levees were designed and built by the US Army Corps of Engineers under direction by the US Congress. New Orleans would not still be in the news had those levees not failed.

Over 70% of New Orleans homeowners had flood insurance and even more also had homeowners hazard insurance. How many homes have flood insurance where you live?

But, my insurance for my property is besides the point. If you crash your car into mine and cause damage and injury, who’s responsible for damage? Who’s insurance pays? I wish mine would, but they won’t unless I have uninsurred motorist coverage – which is not available to homeowners for their homes, AFAIK.

And, guess what? When your home soaks in salt water for a few weeks up to the roof and you are not even allowed to return to mitigate additional damge for at least six weeks and then you cannot get electricity for nine months or have any place to stay while you attempt repairs or rebuild (without schools or healthcare available either) and the same thing happened to all of your friends, family and neighbors, well… your insurance doesn’t even begin to cover that scenario. And, hazard insurance claims have mostly been denied.

It really hurts our feelings that a large part of the US considers our region disposable. I feel that if our government is not willing to act resposibly and compensate flood victims for our losses, then they should make us succeed and then we can fend for ourselves. If the US doesn’t need us, we don’t need them. Hundreds of thousands of US families are truly suffering horribly from the loss of their homes and everything they ever owned. It wasn’t just homes. They lost their jobs, schools, churches, post offices, our small (and large) businesses and hope, not to mention the thousand+ who drowned and the many thousands that died of stress and hopelessness since the levee failures.

While recognizing the many half-truths and outright miscomceptions in Lee’s movie, overall, I felt it was a pretty good depiction of how things feel here – but, the feelings keep changing.

Ray Broussard

Ray:

Thanks for the comment, and for giving a far clearer picture of the situation than Spike Lee did. In a few paragraphs, you’ve hit on nuances that the filmmaker didn’t over the course of four hours.

I think you illustrate my points about When the Levees Broke: that it captures feeling well but not the political and historical context. Its aspirations go beyond feeling, though, and so it’s a failure in my estimation.

And, really, how hard was it to show people who are still angry in New Orleans? It’s pretty much a given.

Nice article, great review, never saw it, it didn’t particularly interest me as a film, I had no idea it was 4 hours long though.

As a Canadian, I remember most of all Canada’s response the day of Katrina. Our Prime Minister called the President and offered New Orleans the use of our DART team (Disaster Assistance Response Team). Katrina is one of the exact scenarios they were trained for. The President asked how quickly the Canadian teams could deploy. The response was ‘4 hours’. America never took us up on the offer. I guess they didn’t want to pay the bill…