(A revised version of this essay can be found at Magnolia82.net.)

(Culture Snob’s first offering for its own Misunderstood Blog-a-thon.)

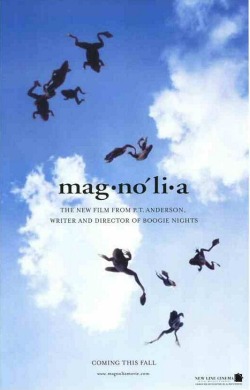

Why does nobody take the frogs seriously? Why does nobody question them?

Why does nobody take the frogs seriously? Why does nobody question them?

In Paul Thomas Anderson’s Magnolia, the cataclysmic, apocalyptic rain of frogs seems casually accepted. Nobody says: “That’s some fucked-up shit, those frogs.”

And I guess it’s a testament to Anderson’s script, direction, tone, pacing, and heavy foreshadowing that I’ve never heard anybody say anything along the lines of: “You know, I was with it right up until the frogs.” I led a small-group discussion on the movie last year, and nobody had any problem with the amphibians, and nobody ascribed a grand meaning to them. As Stanley Spector says in the library, with wide eyes but no curiosity: “This happens. This is something that happens.”

Stanley is a child, though, and it’s dangerous to confuse his extensive knowledge of trivial facts with wisdom. His statement comes in direct opposition to the words of the movie’s infrequent narrator, who admonishes the audience in the prologue not to brush off coincidences and strange events: “This is not just ‘something that happened.’ This cannot be ‘one of those things.'”

So: What are we to make of the frogs?

Most Christians and Jews will recognize the frogs as a motif from Exodus. In case that wasn’t clear, Anderson fills Magnolia with the numbers eight and two (the chapter and verse, respectively, in which the frogs appear) and several explicit references to Exodus 8:2. The frogs are one of the plagues that visit Egypt as God tries to compel Pharaoh to release the Israelites from enslavement.

You probably knew all of those things, but that basic background doesn’t illuminate what the frogs mean, or why they’re so prominently featured in a seemingly irreligious movie.

Magnolia has but one devout character – police officer Jim Kurring – and the script implicitly mocks him as a simpleton whose piety seems contingent on favorable treatment from God. When he loses his gun, he thinks the Lord has abandoned him and begs for help. Kurring is good-hearted but not rigorous in his faith.

And the movie is populated with lost, lonely people. Addicts, adulterers, misogynists. Greedy, mean, egocentric. Friendless, pathetic, stunted. They’re miserable, and many of them are wicked to boot. These characters are so far gone that only something nearly miraculous could awaken them from their moral and spiritual slumber. God’s weapon of choice? Frogs.

You might dispute the divine source of the frogs, noting that reports of natural frog precipitation are hardly unprecedented. But the movie offers no hint of a rational explanation.

More importantly, a scientific accounting for the frogs would render them meaningless as a narrative device. The amphibian downpour would merely be, in Stanley’s words, “something that happens,” no different from a spectacularly heavy rain. And if the frogs are insignificant beyond assisting the plot, then Magnolia must be a terrible, lazy movie. Either the frogs are an essential, pregnant component of the film, or they ruin it.

I subscribe to the former view, and the only way to justify the frogs is to bring God into the picture – the jealous, angry, ostentatious Lord of the Old Testament. Sometimes you gotta break out the big guns, particularly when people are this spiritually dead. Or, as Dixon raps in the movie, “When the sunshine don’t work, the good Lord bring the rain in.”*

And once you have their attention, you can add a little sugar. The climatic fury is tempered in the denouement by the simple truths spoken by Stanley and Jim, and the gentle assistance offered by Jim and Phil, and the mother’s comfort given by Rose. They inject some New Testament values: Love thy neighbor, and treat others as you’d like to be treated. “You have to be nicer to me.” “Sometimes people need a little help. Sometimes people need to be forgiven.”

And sweet Phil Parma, the only character to consistently show empathy and compassion for another human being in this profane place, cries.

Phil wept.

(*Thanks to reader Mark for pointing this out in the comments.)

Actually, I was someone who wasn’t with Magnolia, even before the frogs. Aside from isolated moments (I loved the cast sing-a-long to the Aimee Mann song), the whole film played to me as if the religion in question was Robert Altman (a fine choice for a religion, if you ask me), but it was being preached by a false prophet. The opening sequence with its incredible tales, two of which had previously recounted on the TV series Homicide, made me feel even more like Anderson was just grabbing things from anywhere he could and trying to dress it up to look like his own original creation.

I wasn’t aware that two of those stories had been lifted from Homicide.

I obviously feel more kindly to Magnolia than you do, but I think your criticism of it is more valid than the more-common complaint, which was that it was a mess.

I drew the comparison to Altman in a previous essay – and I get no points for that, I know – mostly to contrast them. There are essential distinctions, for me, in tone and empathy.

To be fair, the stories in Magnolia’s prologue are lifted from general urban-legendhood, as were, presumably, the Homicide storylines. Snopes links! I don’t see anything problematic with lifting existing stories in either case, but then, I have a bad attitude towards narrative.

One thing I forgot to write before (which was one of my principle problems with the movie) is that the Ricky Jay setup leads you to believe it’s about to tell a story of amazing coincidence but in the end, the film isn’t about coincidence, it’s just about a large cast of characters, some connected, some not, who all happen to be in the same place at the same time when frogs fall from the sky.

That’s a very literal interpretation of the prologue.

I read it in a more general way: “Pay attention. Don’t dismiss things just because they’re strange. Give yourself over to the story.”

To me, Anderson is emphasizing the importance of the suspension of disbelief with this particular movie.

As a big fan of “Homicide”, I wonder how the fact that I missed the opening of ‘Magnolia’ affected how I saw the film.

(I finally caught up with the opening just a few weeks ago. Didn’t remember those episodes, but it’s been longer now, obviously, since I saw those episodes.)

“the film isn’t about coincidence, it’s just about a large cast of characters, some connected, some not,”

That’s a quote from a critique a few posts up, i just watched the film my first time 5 minutes ago and if during the movie you look at the tv screen (in the daughters house/apartment ) when the show “what do kids know” as the credits are rolling up you see that the shows creator was Partridge the old man dying, so all of the characters are connected through this single individual which is extremely coincidental, “some connected, some not” i think you may have spoken too soon without actually understanding the films subtleties, there is much more to the plot than is revealed in the cameras central focus. Perhaps you should watch again…

I would have preferred to have not seen the opening vignettes. I was looking for the sort of interlocking lives and coincidences like in the movie “Grand Canyon”. Intead their were two stories (dying horrible father & brilliant wunderkind) that showed through compare/contrast:

1) The reprecusions of the choices we make

2) The power of forgiveness

The opening sets you up for a WTF! moment that never comes. Instead, the opening should have been stories about how a minor choice can change a life forever. For example, I think there is a case of someone who didn’t go on the Titanic because they were late or the famous coin-toss that resulted in the death of Richie Valens.

Is it a fucking coincidence that I just wrote a 4-5 paragraph essay on my thoughts on the movie Magnolia, typed in the “CAPTCHA”, and previewed it. Now, it’s mysteriously gone….if it doesn’t show up, I was writing it for the feedback of Culture Snob…..Come off it, I’m the prophet…gonna tell you ’bout the Worm…Fuck!!!! I hate computers, whenever I write something that takes more than 2 minutes, it disappears! Zoe in Sarasota

Zoe: The computer ate your comment. No sign of it on the system. Sorry.

If you preview the comment, you also need to repeat a CAPTCHA on the preview page.

if it’s a string of quote-unquote “coincidences” you want, sit down and watch all three seasons of lost.

i love that they HAVE managed to run these people in and out of each others’ lives before the flight even took off, but lost has now had close to 70, 45-minute episodes to get the job done and they’re still going…along the way, you realize that a lot of coincidences aren’t important in and of themselves, but it’s how something so seemingly trivial could have a tremendous affect on someone’s life.

that’s what i got out of the “coincidence” thing in magnolia…while there may not have been one big BANG…CHECK OUT HOW WE WACKILY BROUGHT ALL THESE PEOPLE TOGETHER!!!! WHOAAAAA!!!!!! moment…anderson told a story that showed how all these people who outwardly would SEEM to be so unrelated are actually pretty closely related…

at least that’s my take on it.

Spoiler warning: This movie is a Waste of 3 hours of your time.

falling frogs face first

I know I’m *years* behind you, but I actually listened to the “Drunken Commentary” you did with your wife way back when while I watched “Magnolia” for probably the fifth time tonight. I know you have the script, which is where you looked this up, but Phil Parma actually doesn’t ask a question in the movie. He simply states, “Oh, there are frogs falling from the sky.” If you run the subtitles while watching the movie that’s what he says. The only deviation is that he adds the “Oh” and that isn’t in the text.

Epiphany: According to the script and the subtitles, you are correct.

However, I’m not convinced that Philip Seymour Hoffman doesn’t pose a question. The delivery and tone aren’t consistent with the statement “Oh, there are frogs falling from the sky”; they are, however, consistent with the questions “How are there frogs … ?” or “Why are there frogs … ?”

Subtitles are often incorrect, and there are almost always deviations from the shooting script. That said, my hearing of the line deviates from more-authoritative sources. So I’ll be wrong here.

The offending phrase has been excised.

(For posterity, this essay originally read: “In Paul Thomas Anderson’s Magnolia, the cataclysmic, apocalyptic rain of frogs seems – outside of this essay’s titular question, posed in the movie by nurse Phil Parma – casually accepted.”)

maybe the writer forgot what the giant coincidence was going to be so he said … “Screw it. Falling frogs!”

All of the characters are connected. If you watch the credits at the end of the quiz show, Earl Partridge, Frank’s father, is the producer of the show. Both Earl and the host of the show have done terrible things to their children when they were young. They are both now dying of cancer, and their children want nothing to do with them.

Linda married Earl for his money. Now that he is finally dying, she has fallen in love with him for real. This is her punishment.

Donnie, the now grown up quiz kid and young Stanley are following the same path. Donnie says he has love to give, but he doesn’t know where to put it. Stanley will be the same way if his father doesn’t start being nicer to him, as he asked toward the end of the movie. Not having love while you are a child makes you unable to love as an adult. This is why Frank feels the way he does toward women, and why Claudia is so messed up.

The frogs were an intervention. They made Claudia step away from the coke, and her father drop the gun. They made Donnie put the money back that he stole. They also gave Jim back his gun, his power. Tho the simplest character, he was the wisest, and made the most sense of it all. Stanley, who we thought was the smartest character, said this is just something that happens. Jim said this isn’t just something that happens. Everything happens for a reason. The 3 stories at the beginning of the movie also happened for a reason.. This is God’s plan.

I’ve seen the movie multiple times, and it strengthens its’ themes of life NOT being something for us to control and not being safe or wrapped up neatly. First you have the opening monologue, then you have the greater suspension of disbelief with that song they all sing (which could and probably does happen every day. I like to sing out loud, I like certain songs that others surely do, etc). Then you’ve got the frogs at the end. After all the stories have built up to a frothing climax, it’s not about whether the frogs are from God or a freak storm, it’s about how the characters see the event. None of them openly question it, but we know they’re mostly intelligent and perceptive just as we are. The policeman for example ended up taking a huge emotional risk by going to the lady’s house.

The words I’m looking for are getting increasingly more difficult to come by, as it’s late for me. But I felt the urgent desire to write something, ANYTHING, about the glories of this film. For more context, I’d suggest the detractors watch something like Nashville, or just stay the freak away from ‘serious movies’ and stick to fare like Transformers.

wow, i saw “magnolia” for the first time just now…right after watching “transformers” for like the 100th time…weirrrrd…loved “magnolia” tho.

Thanks, Culture Snob, for this excellent series of Magnolia analysis. Last night I watched it again for the first time in ten years, having seen it (and loved it) 4 or 5 times when it was first released. I’ve since waited impatiently for other such moments of filmic brilliance, only to be fully satisfied by There Will be Blood and more recently by Synecdoche, New York. I would love to see you delve into the many complex, perplexing, and fascinating details of Synecdoche. It requires multiple viewings and though I’ve spent some time trying to fully understand it by myself, you are far more prepared and capable of doing it full justice. There is plenty of existing analysis of it out there–but it is most often trite, poorly written, and riddled with superfluous hyperbole. Consider it?

I just watched “Magnolia” for the first time, and in the daze afterwards I stumbled on this article. I found it very interesting, but after looking on imdb I found that Anderson had the idea for the frogs before being aware of the biblical story. It was after finding out that he incorporated all the 8s and 2s. What do you make of that? To me it means that, on one level, Anderson incorporated the religious story into his film which definitely makes it relevant when discussing the frogs. I get that. In fact, it’s easier for me to process this way. But, on the other hand, that means Anderson had this idea as the original ending anyway, without any religious framework. What the hell does that mean? I guess it could still suggest God interfering, and maybe it does. Maybe it’s just a huge coincidence that he thought of that and then found the perfect story to support this image. Anyways, something to think about.

Nathan: I prefer to look at the text rather than what the creator intended, or what the creator intended originally. And regardless of direct references to Exodus, the rain of frogs is inevitably going to be interpreted by many people in its cultural context. That is, it’s going to be read religiously, and it’s a valid interpretation no matter what the creator intended.

But if we’re going down this path, I’d say that many good or great ideas were born from bad ones. So if Paul Thomas Anderson initially intended the frog storm independent of religion (which I think would be a bad idea), that doesn’t affect how I feel about his ultimate decision to reference religion (which is a good one).

Isn’t the frog storm supposed to be ironic? After seeing multiple characters in their cars, and knowing that many of these players have connections to one another, then isn’t the trained viewer supposed to expect some deus ex machina. Except Anderson plays on the term and gives us something completely (un)natural. I feel like it is equally as Greek as it is Hebrew, and i think Aristophanes would agree.

Seeing Is Not Believing

In Magnolia, we witness a visible and cataclysmic act of God. But in a strange paradox, no one in the film – nor those of us watching the film – recognizes its significance or even acknowledges the role of God. How could we? For the magician-director completes his trick by cueing the narrator for the final distraction. When the falling frogs stop, the narrator emerges again to blur any meaning we might have discerned:

“There are stories of coincidence and chance and intersections and strange things told . . . And which is which and who only knows? And we generally say, ‘Well, if that was in a movie, I wouldn’t believe it.’ . . . And it is in the humble opinion of this narrator that strange things happen all the time. And so it goes, and so it goes. And the book says . . . ‘We may be through with the past, but the past ain’t through with us.’ “

Anderson’s sleight-of-hand returns once again in the narrator’s meandering monologue. We are encouraged to accept the fact that these things happen all the time, and that we shouldn’t over-think any of it. Focus your attention instead on the juicy piece of meat – the last sentence. The profound yet irrelevant quote: “The book says, ‘We may be through with the past, but the past ain’t through with us.’ ” It’s a quote taken, appropriately enough, from, The Natural History of Nonsense by Bergen Evans. We should consider the whole thing “nonsense.”

But if we can see past this distraction then we can discern Magnolia’s deepest subtext. The frogs reveal Paul Thomas Anderson’s longing for a visible and tangible experience of God. One need not be “religious” to long for a cataclysmic and visible sign from heaven, a sign that we are not simply living in the chaos of a meaninglessly spinning world. Deep down, in secret places, we long for something so tangible that no one can deny it was divine intervention – like Jules’s (Samuel L. Jackson) near-death experience in Pulp Fiction. When we see it in reality, we will know it is truth.

But that’s the trouble. Reality doesn’t tell us about truth. Unfortunately, the stubborn world of truth is not expressed or accepted in a real world that is seen. We nonetheless continue our longing for truth to be made visible in this tangible world. We go on believing that if we just see something for real we will believe it is true. But reality never seems to last. As soon as it happens it begins to decay. Reality, residing in memory, has a half-life, but truth, which does not live in our mind, is far more tenacious.

The visible plague of frogs faded in the Pharaoh’s memory, its effects present only as long as he could see them. It is no coincidence that his part of the Exodus story does not end well. The response from Stanley’s father reveals that the effect has, similarly, already begun to decay for the adults in Magnolia.

And the book says, “Blessed are those who have believed but have not seen.”

Strange things happen all the time. This is the belief of the narrator. If we see it in a movie–or perhaps read it in a book–we are inclined not to believe it–but our narrator assures us that these strange coincidences do happen all the time. But the narrator is telling us about a strange coincidence that did “really happen” even though we are inclined not to believe it because we are seeing it in a movie.

The only allusions to God or religion in the film are the symbolic links to Exodus, where that narrative is explicitly about God and “strange events” that “really happened”. But here too we are faced with irony. We are disinclined to believe those stories too, having read about them in a book, even though strange events like that “happen all the time” in the opinion of our narrator.

But in contrast to the ancient stories, our modern or perhaps “post-modern” story is ambiguous. We do not see clearly the hand of God intervening in judgement, against the sins of the oppressors. Instead we see coincidence, and are left to infer if there is any meaning to such strange things, or if they are just strange things and nothing more.

Some have claimed that after the “rain of frogs” we see a new reality emerge. Perhaps the sins of the fathers have been healed or forgiven. People have been saved, in the words of the Aimee Mann song. The gun is returned. The addict seems freed from her addiction. This is what we would expect from the biblical narrative, where the plagues save the people from Pharaoh. But we don’t believe those strange things anymore, so we aren’t sure. In a postmodern move we are left wondering, with different perspectives: “It happened, it really happened,” but is it a coincidence? After all, strange things happen all the time. There is no certainty of a divine intervention, of a forgiveness and a redemption from the terrible effects of the sins of the fathers, visited on their children and their children’s children–especially if we see it in a movie, or read of it in a book.

Franks’ father dies looking into the face of his son. Is there forgiveness? Perhaps not. As mentioned, the nurse weeps. The other father’s suicide is, ironically and coincidentally thwarted by frogs, but this is no act of forgiveness, just a random coincidence according to our narrator. His drug addicted daughter seems better, and the cop also leads the Macy character to make restitution. But the boy who longs for his father’s love, like Frank, is coldly rejected. There is left, in the experience of those “in the movie”, only the random coincidences of strange events, and there is no clear hand of God, no clear sense of meaningful redemption or forgiveness. There is for some and not for others: “and so it goes, and so it goes…”

But we are at least reminded, in the book, that the past isn’t through with us. Even if we cannot see a clear hand of God, as was so clear in the Exodus, the past will continue to hold us in its grip. Every now and then things will get so bad, and our sins will be so destructive of our relationships, that only a plague of such frightening proportion will be sufficient to re-orient us to a new future. For some that will be the intervention of God, but for others, merely a random strange event. Post-modernism is all about perspective, and there are multiple perspectives in this film, with no meta-narrative to guide us, only ambiguity.

Thanks so much for this post. I actually reference it in my own piece about the topic, which can be found here: http://wordsonfilms.com/2014/06/21/and-then-there-were-frogs-lots-of-frogs-frogs-falling-from-the-sky/

Clearly, there are a variety of ways in which one could choose to interpret the frogs in Magnolia. And yet, I do tend to favor a rather simple understanding of them probably because I’m simple, but we’ll ignore that for now. Above all, I think the frogs are the film’s most memorable declaration of the fact that you simply can’t predict the future. Magnolia is an ode to the unpredictable. For the most part, life doesn’t turn out the way Anderson’s characters planned. Similarly, none of the weather forecasts in the film predict a downpour of frogs. Thus, the frogs come as a slap in the face (or, perhaps, a harsh dose of reality) for those foolish enough to claim that they know what the future holds. In that way, they are a sort of summary of the entire film.

I’ve watched this movie numerous times. I didn’t understand the frogs when I saw it the first time, but, nearly 15 years have gone by and I’ve watched it 3 times in the past month and I have a different perspective on it now. I needed to find out what the frogs symbolized because I was affected not just because of the phenomenal actors, but, because of how much I related to some of the characters. I’m especially influenced by Phillip Seymour Hoffman’s performance and wish he was still alive to pick his brain about what he thought….R.I.P.

I am convinced I have the answer:

it doesn’t have to be crazy complicated or religion based… and it just dawned on me now…

furthermore… I think the trailer provides the answer, clearly and concisely – “when it rains, it pours.”

In frog scene helps open up and conclude the climax. EVERYTHING/EVERYONE has just undergone a plethora of pain, confusion, loss, abuse, revelation, disappointment, dissolution and suffering – everything comes together and culminates into one big ‘sh*t storm’, so to speak that it could and should potentially prove too much for the viewer to digest.

and so the clouds part… and the frogs fall, as if to indicate explicitly that the cast of characters have such large crosses to bare, that some relief or respite is in order.

again, in summary – the frogs are a way to reiterate that message – in the movie Magnolia, went it rains, IT POURS.

meep!

Magnolia is Paulk’ s best work aside from the opening single shot in Boogie Nights.

This movie was ahead of its time.

I never knew about the Exodus reference until I read about it.

I always look at the frogs as a Deux Ex Machina.

One thing “wrong” , for lack of a better word with movies in general, are their endings. In Theatre, DEM was the way they would end the piece. This is the frogs in Magnolia.

The movie is absolutely brilliant. I remember first renting it on two VHS tapes. This movie resonates. It has sdtasying power. And how Tom Cruise “list” the Oscar to Michael Caine I will never know. I reference his performance in my Film class all the time.

One piece of advice for movie “scholars”: stop being so cerebral and stop trying to be so clever and use observation. Parroting what others say is just simply sad . The only way for your thoughts to ring true is to make them be your own.

Pretentious garbage with a super-simple message. Boring.. Movies are supposed t be entertaining.

I think your interpretation is right, and hinted at in the script:

“When the sunshine don’t work, the Good Lord bring the rain in.”

Just watched Magnolia and find reading the comments very interesting. Any thoughts on the kid with the rap and the dead guy called “the worm”?

I believe a simple way to interpret the frogs is to know that Exodus 8:2 is about a cataclysmic event which helped (but did not fully accomplish) the freeing of slaves. Most of the characters in the movie are slaves to their past. Even Stanley, who is a child, studies wunderkinds from the past to learn their fate.

The frog scene does not signal a moment of complete redemption for the characters, but it is the beginning of hope that freedom may be coming. Even the two thwarted suicide attempts support the message that true freedom from the past cannot be achieved by running from it; it has to be faced honestly for healing to come.

I’m 70 yrs. old and saw the film for the first time last night. At first, I was tempted to eject the disc and return to solving Sudoku puzzles. As fate would have it, I opted to continue watching. So glad I did. I came away from this wonderful film with question after question about what it might all mean. The characters…the dialogue…all very familiar to me, for better or for worse. Some films make me feel robbed if I can’t understand what their true meaning is all about. THIS film, however, leaves me feeling fuller even amid my lack of understanding. Somehow this director has connected me to another version of myself thru the magic or mendacity of these characters who were flawed to perfection. Reading these comments are extremely helpful to me in mining the landscapes of this film as I seek to glean all of the riches it holds. I’ve steered clear of the director’s other film “Boogie Nights” but, after seeing “Magnolia”, I might take a chance on it. What could possibly go wrong? It’s not like it might rain frogs.

I think you should look into Gabriel Garcia Marquez and magical realism, specially in his most famous book, One Hundred Years of Solitude.

I would like to mention in the beginning of the movie during the game show one of the audience members we’re holding up a sign Exodus 8:20, I think this is very significant in regards to the episode of the frogs falling from the sky. They definitely coincide as these elements are addressed at the beginning and the ending of the film

Ricardo Diaz: Perhaps my favorite book! My memory is bad, though. Is there something similar that happens?

Elle Christian: Yep. And if I remember correctly, that sign is held by the writer/director, Paul Thomas Anderson.