Unknown White Male

Because I do have a memory – not a very good one, but a memory nonetheless – I can save myself some work by providing filmmaker Rupert Murray with a few lessons I’ve learned from other movies and simply link to previous essays.

Because I do have a memory – not a very good one, but a memory nonetheless – I can save myself some work by providing filmmaker Rupert Murray with a few lessons I’ve learned from other movies and simply link to previous essays.

Lesson number one: Let the story tell itself.

Lesson number two: When you’re dealing with people who have lived in front of cameras, you have an additional burden of proof to establish their credibility.

Murray’s Unknown White Male is a fascinating but headstrong and immature documentary about amnesia. The film’s subject found himself on a New York City subway one morning in 2003, not having any memories of his previous life.

He turns himself into the police but has no identification and doesn’t know his name. The cops send him to a psychiatric ward. The staff asks him to sign his name, and he does. It is illegible except for the first letter of the first name: “D.”

In his backpack is a piece of paper with a name and a phone number on it, and that leads to a woman who used to date the man. His name is Doug Bruce. He is 35 years old. He is a former stockbroker – based on his obvious financial resources, he made millions – who has taken up photography.

It’s a great story, and the strength of it might convince many people that Unknown White Male is a good movie or better.

It’s not. Murray’s first sin is that he’s a show-off and doesn’t trust the story or the audience. His second sin is that he doesn’t have an inkling that this tale is, in the truest meaning of the word, incredible, and that his young, video-savvy interviewees are so comfortable in front of the camera that they sometimes come off as actors, further casting the movie’s authenticity into question.

Lesson number one comes from Nick Broomfield and his filmed Spalding Gray performance piece Monster in a Box. To phrase it more forcefully than I did previously: Get out of the fucking way.

With it fish-eye shots and a nearly endless succession of pretty inserts unrelated to the movie’s content, Unknown White Male certainly looks good, but in a way that doesn’t support or enhance the narrative. Murray seems hell-bent on dazzling us with his style – the compositions, the aggressive use of surround sound, the compulsive editing – but his choices rarely contribute to meaning; the director has no sense of cinematic economy.

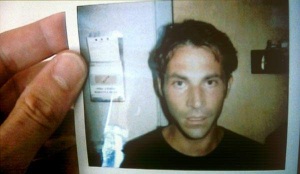

I could pick a half-dozen shots that would have made for compelling openings for the film – Bruce’s searching, uncertain camera in the airport when he visits his family for the first time since the amnesia, for instance, or that lost, blank face in the Polaroid taken at the police station, or the series of incisive, humane portraits of friends that Doug takes after his amnesia strikes – but Murray (after assaulting us with split-second images) chooses a long shot of the New York City skyline. How dull and wasteful.

If that weren’t bad enough, his clunky voice-over narration explains to the audience why he decided to make this movie. It’s thoughtless, dumb writing that’s no more sophisticated than a grade-school essay titled “What I Did on My Summer Vacation.” That audio introduction is the surest sign that Murray doesn’t respect his audience and probably hasn’t even considered it; an introduction that blunt and coarse is downright insulting.

Murray should have spent time with Broomfield’s film of Gray’s monologue to learn about making a documentary. The largely unadorned Monster in a Box teaches that when you’ve got material this good, your best bet is to let the cameras roll and make the narrative do the heavy lifting. Minimize or eliminate cuts, fancy shots, audio augmentation, and unnecessary narration. Recognize that your job as a director is to serve the story, not necessarily to hack it up into thousands of pieces and make sure it looks super-duper spiffy.

That lesson is one that Murray – a first-time director with Unknown White Male – might learn on his own with a few more films under his belt.

The second lesson is more problematic, because learning it would involve crafting a much different movie. Murray’s pre-amnesia acquaintance with Bruce was the reason he embarked on Unknown White Male, and there’s an obvious emotional investment in the picture beyond the work that went into making it. Murray was close to his subject, and as a result he didn’t anticipate that some people in the audience would find it hard to swallow.

But since its premiere at the Sundance film festival in 2005, many people have questioned the film’s veracity, and it was then that Murray should have gone back and fleshed out the movie to address the concerns of skeptics. It’s common to mock the test-screening process that many movies go through because of the way it panders to audiences, but there’s an undeniable value in getting and considering objective feedback, even if it’s ultimately rejected.

It’s evident that Murray never did that. In the bonus materials on the DVD release of Unknown White Male, he’s still incredulous that anybody could doubt the truth of his movie. He continues to find fault with the audience instead of himself.

But doubt people do. Some people think that the documentary is genuine but that Bruce has made up his amnesia to essentially re-start his life. Others have wondered if the documentary is a collaborative hoax.

Both accusations have the same root: the sneaking suspicion that everything in Unknown White Male is a little too neat. Bruce’s amnesia seems conveniently comprehensive, in the sense that experientially he’s little more than a child in a thirtysomething body, discovering the wonders of the world, friendship, art, and love. (Awwwww … .) And the photogenic people who are interviewed and documented seem awfully comfortable in front of the camera.

Lesson number two comes from Andrew Jarecki’s documentary Capturing the Friedmans, which was ostensibly about the sexual-abuse prosecution/persecution of a family. On the surface, the two movies couldn’t be more different, but they share one major similarity: Their subjects are people who’ve been recording themselves for years and have a certain love affair with an assumed future audience.

Jarecki’s film was particularly smart in that it understood the effect of that constant performance for the camera – that audiences won’t trust what the people in the movie are saying. From this we learn that if your audience is going to be skeptical of your subjects, your movie should anticipate and mirror that skepticism.

In the case of Capturing the Friedmans, the movie’s actual subject is truth, and the difficulty of knowing it. Jarecki guided viewers to certain conclusions – that there’s a strong likelihood that some sexual abuse took place even though the court system railroaded this family – but didn’t preclude other readings of the people and events portrayed and described. It’s a probing work of uncertainty.

Murray’s movie, on the other hand, asks audiences to take a lot on faith. There’s no evidence that Bruce was ever tested to determine whether his amnesia was genuine, and no expert saying on film that Bruce wasn’t faking it. Some interviewees aren’t identified by first and last name. The f

ilm acknowledges that there’s no accounting for Bruce’s amnesia in the absence of a triggering brain trauma but then doesn’t question the amnesia. These are baffling omissions, and they’re particularly frustrating because of the promise of Unknown White Male.

Yet here we must acknowledge the special circumstances of the film; it’s a movie based on special access to the subject – Murray’s friendship with Bruce – and then hamstrung by that filmmaker’s shortcomings. While I desperately wish that somebody else had made this movie, it is – for the worse – a film that only Murray could make.

I’ve never even heard of this film, and as I read your description of the early self-discoveries he makes it was indeed a truly fascinating account that made me consider forgoing your opinion, in hopes that perhaps my tastes would forgive. Sadly, your description of the cinematographic ‘pizzazz’ makes me return to my long list of pre-selected viewing rather than add this to the fold. I guess my question is, are you aware of any documentaries about amnesia that are this interesting, but honest too?

Squish:

First of all, I would never try to dissuade anybody from seeing a movie that piques curiosity.

Just because I dislike something doesn’t mean you will, too. And more importantly, even deeply flawed movies are worth seeing if they have interesting things happening.

So while I disliked Unknown White Male and find it deeply flawed, interesting things are happening, and it’s worth seeing.

Second, I wouldn’t call Unknown White Male dishonest; it’s poorly made and too earnest.

But to answer your question, I don’t know of any other documentary about amnesia. There are lots of documentaries that deal with memory, of course.

These days I’m going through repertoire stuff, you know just so I can be a critic who knows what he’s talking about, a guy with context. When I see something out there that I’d never heard of, I compare it to my list of ‘must sees’. Very few new films make the cut.

It’s been over 2 years now and I’ve just added this to my ziplist. It’s been on my mind and damn it, I’m interested!