Now that filmmaker Robert Altman has died, we’ll find out how prophetic his 1990 film Vincent and Theo turns out to be. The movie, ostensibly a portrait of the relationship between Vincent van Gogh and his brother, operates most forcefully as a screed against the commercial pressures foisted on artists, and it’s easy to see as a metaphor for Altman’s own career.

Now that filmmaker Robert Altman has died, we’ll find out how prophetic his 1990 film Vincent and Theo turns out to be. The movie, ostensibly a portrait of the relationship between Vincent van Gogh and his brother, operates most forcefully as a screed against the commercial pressures foisted on artists, and it’s easy to see as a metaphor for Altman’s own career.

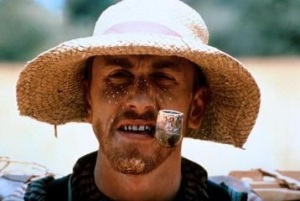

The movie’s framing device is blunt yet elegant. It begins with the contemporary auction of a van Gogh painting, and when it jumps to Vincent’s life, the auctioneer’s voice can still be heard, the bids climbing ever higher. That slowly fading audio juxtaposed with an idling Vincent, anxiously adjusting his pipe while sitting on his bed, suggests that the artist had an inkling of his talent, and perhaps even foresaw his destiny: posthumous riches following a life of poverty.

Altman avoided that equivalent fate, barely, kind of. Nominated five times for the best-directing Academy Award, he was given an honorary Oscar this year.

Yet while the gold statuette is the pinnacle of respect in the eyes of the casual movie-going public, it’s an inadequate honor. Martin Scorsese will one day get his own lifetime-achievement Academy Award, but – this week at least – he seems merely a highly respected filmmaker. Altman made a far deeper connection with his audience, as evidenced by the profound grief that has greeted his passing; it’s almost as if a family member died, which is all the more remarkable considering that (1) movie directors are at best secondary celebrities, and (2) he was 81 years old.

Some starting points: Dana Stevens at Slate, assessments and an open thread at The House Next Door, the Robert Altman Blog-a-thon from earlier this year, and Jim Emerson’s Altman moments.