An Interview with Martin Mull

In the 1985 HBO mockumentary The History of White People in America, co-writer and host Martin Mull offered the world mayonnaise-loving WASPs – suburbanites who had lost any sense of their roots, to the point that one child’s understanding of his own heritage was limited to the streets on which he and his parents had lived.

In the 1985 HBO mockumentary The History of White People in America, co-writer and host Martin Mull offered the world mayonnaise-loving WASPs – suburbanites who had lost any sense of their roots, to the point that one child’s understanding of his own heritage was limited to the streets on which he and his parents had lived.

White people, the show seemed to be saying, are beyond ethnicity and culture.

Mull doesn’t see a meaningful connection between that work and his paintings, which are presently touring the country in a retrospective. The only link, he said in a recent interview, is that they reflect his childhood in Ohio. “It comes from the same vein,” he said, “the same mother lode.”

Yet they share more than just a Midwestern upbringing. The History of White People in America is the light-comic flip side to Mull’s ambiguous but loaded paintings. Both represent a tug of war over the American dream, a recognition of both its allure and its pitfalls.

The retrospective exhibit, which includes roughly 40 works from the past 22 years (with an emphasis on large oil-on-linen paintings from the past decade), is called Adventures in a Temperate Climate and originated with the Las Vegas Art Museum. It finds Mull fixated on the 1950s that were portrayed in magazines and on television shows of the day – defined by sunny conformity.

“Even before I started doing the somewhat photo-real kind of assemblage collage-ish kind of stuff – working from ’50s photographs and so forth that I’m doing right now … – I was working with children’s books, illustrations that I had gleaned from my own childhood,” Mull said. “I’ve always had a certain fascination. It’s basically ‘paint what you know,’ and this is what I grew up with.”

But Mull isn’t employing this iconography for mere humor, and he’s not casting it as ironic fantasy. There’s a sadness and longing tied into many of his images, in the way they’re lovingly re-created in paint. For people who grew up in the 1950s, he said, many of the paintings will bring with them a lot of baggage.

“It was taunted as reality,” the 63-year-old Mull said. “It was dangled as a carrot. In terms of people’s hopes and dreams, to say that that is less of a reality than the daily grind they find themselves in is maybe not correct. Your hopes and dreams tend to figure very prominently in what makes up your life. And that’s what those things were: They were promissory notes of the quote-unquote ‘better life’ that were unredeemable.”

Yet Mull doesn’t want to circumscribe people’s experience of his work and is hesitant to even assign meaning to the paintings; he claims that he makes “pictures,” not art.

That self-deprecation – whether earnest or an act – extends to his fame. He will grudgingly talk about his career as a comedian and actor but derides it as merely a job.

Painting Money

Unlike many celebrity artists, Mull got his training in fine arts, graduating from the Rhode Island School of Design.

And although the bulk of his money came from performing – with a series of comedy albums in the 1970s and a television and movie career that span from Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman to Roseanne to Sabrina, the Teenage Witch – he claims that painting has remained his true love.

“I’ve been doing it all along, ever since I got out of art school. I got my master’s in ’67 – wow, I’m old – and never stopped making pictures. There were times when more of my income was coming from other sources, and I had to devote more time to television and movies and records, things like that. … Around 1980, I went back to it [painting] with a vengeance.”

When talking about his paintings, he’s downright dismissive of his work in show business, including more than a hundred credits in TV and film. He sounds as if he can barely bring himself to say the words “show business.”

“I kind of just lucked into and fell into the other profession,” he said. “It was really just an outgrowth of the fact that when I was in art school, I had no money whatsoever.”

Yet there’s no denying that it’s Mull’s fame as a comedian that has given him a platform for his painting. Even if you find his painting compelling, Mull as an artist clearly draws some of his sparkle from his celebrity.

“It really is a day job, and it also seems to have virtually disappeared,” he said of acting. “With no remorse, really. It gives me more time to paint.” That disavowal of a profession that has been relatively lucrative is curt, but it fits with Mull’s philosophy of art.

“I had a teacher in art school who said something about the only works he really enjoyed seeing or found much in were works where he had a sense that a discovery was made in the course of making this object,” he said. “I kind of like to hold to that as my marching orders, to not get to the point where one is making wallpaper, or … simply painting money. I want to make sure that I am at least trying to weigh myself down, that there’s a challenge each time.”

As for acting, “You’d be surprised at how undemanding it is,” he said. He used his dressing room on Roseanne as a studio, he said.

Through the Cracks of Daily Work

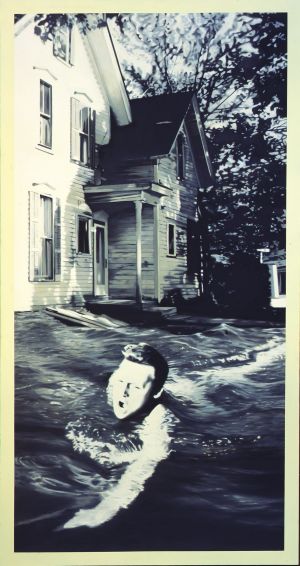

The paintings themselves are likely to resonate differently with each generation. Those of us who never experienced the 1950s might read the jarring juxtaposition of vacation preparation and a house ablaze (in The Importance of an Annual Vacation) as a commentary on willful ignorance, the unbreakable façade of normalcy even in times of great duress. A man seemingly gasping for air while swimming in water that laps at his home’s doorstep (in Modus Operandi) is easily seen as an indictment of the consumer culture that still threatens to drown many Americans.

Yet those paintings are outliers, some of the most pointed in the exhibit. And while not denying any interpretation, Mull doesn’t subscribe to any of them. “Some of the pictures I must say every now and then I just think are going to be funny,” he said. “When it gets that much, you might as well just pull out all the stops and make it more of a burlesque.”

Most of Mull’s paintings are foggy, though, open to a wide variety of readings. I find The Aerialist, with a young girl in a dress on a high wire while two adults look on, distressing, but I can’t pinpoint the source. The placidity of the scene undercuts any sense of danger, while the busy, organic floral frame is balanced by interior dead space and two strong, straight visual lines.

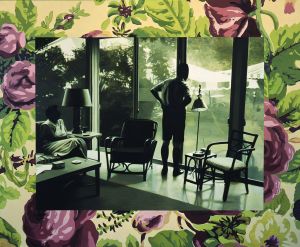

In The Joys of Indoor/Outdoor Living, a man and woman are captured in their sun room. This domestic scene might seem surface-pleasant, except in the way that the subjects appear trapped by glass, prisoners in their own palace. This effect is achieved almost entirely by s

hadow.

In Parents I, Mull combines unrelated images – Minnie Mouse holding a birthday cake, and a young boy with a shovel, both standing atop the greenish blur of a suburban landscape as if glimpsed from a speeding car – to load the piece up with memories and cultural luggage. Some might find the painting comforting and whimsical, while others will sense a dark current.

And Impractical Matters, featuring a grouping of four children and a locomotive rendered in a different style, is patently benign in terms of its content. Yet there’s something about it … .

Mull describes the effect well, saying that his painting has evolved. “The imagery is getting a little more enigmatic,” he said. “I’d like to think that it’s getting a little more evocative without being more narrative. And that makes me think that it might be something in the actual structure of the paintings that is starting to come around finally. And that’s exciting to me.”

But he doesn’t claim that the works have inherent meaning. “As far as messages, I kind of go with what old Sam Goldwyn said years ago, that messages should be sent by Western Union,” Mull said. “I don’t think you really can … send an exact message, because … any two viewers are so disparate, in terms of their backgrounds, their point of view, their histories, that there’s no telling what that message might be.”

People in their late 50s to early 70s, Mull added, have been fond of his work. “They seem to have a much greater attachment to the stuff,” he said. “There seems to be a sense of melancholy, and a kind of warmness with which they approach the work. … It maybe works for a specific generation. It may be the AARP commemorative stamp.”

Mull said that he continues to find inspiration in the 1950s, and has rarely worked outside of that decade over the past five years. “Instead of exhausting that vein, it seems like the opportunity just increases exponentially,” he said. “There doesn’t seem to be much stopping.

“I think there are a lot of pictures to make. … I really kind of sometimes question whether I’m even an artist or just a painter. To me, the making of the pictures is the most important thing.

“To be able to just get up in the morning and be in my studio and work all day is just a great joy. I also tend to think that we can get extremely self-conscious slash self-important if we start seeing ourselves as artists. … If there is some art involved, I’d like it to be that it came through the cracks of daily work.”

Mull said that he paints for between six and 12 hours a day, primarily on large linens. He occasionally works in a smaller size – 20 by 24 inches, for instance, or 18 by 20. “When I go back to the larger ones then, it just seems like they have increased threefold,” he said. “The reaction then to a 60-by-72-inch canvas after I’ve done a small one, I almost feel like I’m doing a billboard.”

Mull, with a modesty that sounds genuine, suggested that his painting is somewhere beyond adequate. “You’d have to think that you’re at least decent or you couldn’t get up every morning and do it,” he said. “I think if I live long enough, I might be pretty good.”

This article originally appeared, in slightly different form, in the River Cities’ Reader.

His ideas are unique! Mull’s way of combining ordinary or normal pictures to cartoons, wallpaper-like images, and others is so intriguing. I love that man swimming. Are these mere pictures put together one after the other? Or are these real paintings?

John

John:

Those are paintings rather than collages. My understanding of his process is that he draws inspiration from old magazines and books.