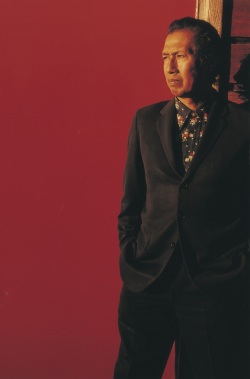

An Interview with Alejandro Escovedo

It is in times of crisis that a person learns who his or her true friends are. Alejandro Escovedo discovered he has a lot of friends.

It is in times of crisis that a person learns who his or her true friends are. Alejandro Escovedo discovered he has a lot of friends.

Even if you haven’t heard of Escovedo, you’ve likely heard of them: John Cale of the Velvet Underground, Los Lonely Boys, the Cowboy Junkies, Son Volt, Charlie Musselwhite, Lucinda Williams, Calexico, Steve Earle. Those people and more than two dozen others cut tracks for Por Vida: A Tribute to the Songs of Alejandro Escovedo. The goal wasn’t merely to honor the man, or just to offset some of his medical bills, but to perhaps save his life.

Singer/songwriter Escovedo is widely and deeply respected in the alt-country community, and he has the meager bank account to prove it. He even called his live disc More Miles Than Money. The alternative-country magazine No Depression called him its artist of the decade for the 1990s.

His collapse at a 2002 performance was a public sign that the Hepatitis C with which he had been diagnosed was winning a battle for his body. The disease nearly killed him. After several years of convalescence, Escovedo has made a full recovery, but he didn’t have health insurance. That’s where those friends came in. Por Vida was released in 2004, and Esovedo said in a recent interview that the project was critical to his recovery.

“At first I thought it was going to be something local,” he said. “We’d get some friends on it. And then it just started to snowball and it became this amazing thing. And then, finally, people were sending their versions of songs in. I think the first one we got was John Cale. … It really saw me through the worst part.”

Escovedo didn’t write or play for a year and a half as he recovered. During that time, his father died. “Music wasn’t really a driving force behind me wanting to survive that disease,” he said. “It was more about wanting to see my family, and my kids grow up. … That was my main concern.

“Once I started to get healthier, the things that I love all started to reintroduce themselves into my life, music being the most important of all of the things after my family.”

Escovedo and his band began playing shows again in October 2004 in their home base of Austin, Texas, and last year started putting material together for a new CD, with Cale (an acquaintance since 1978) as producer. “John, he’s a very intense person,” Escovedo said. “I think that intensity is what he brought to it. We knew that it was an important record to make, and that people were expecting something pretty great … or pretty intense, at least in terms of content, because of what I had been through.”

The Boxing Mirror was released in May 2006 to enthusiastic reviews – clearly not charity notices out of respect for what Escovedo had been through. The All Music Guide could barely contain its glee: “It’s music that combines real-life poetry with a prismatic vision of life under the skin, in the place where the heart pumps real blood; emotions get tangled up in this mix and are expressed in unexpected, often uncomfortable, ways. The Boxing Mirror reels and struts, waltzes, and falls down, but always gets back up again. Rock-and-roll music has been extended in the various articulations of these songs. In the 21st Century, this is what singer/songwriter albums are supposed to sound like. The Boxing Mirror is brilliant, and it is his masterpiece.”

“I didn’t want a black record,” Escovedo said. “I didn’t want it just to be about Hepatitis C. I wanted it be about having gone through that experience. It could have had something to do with Hep C or not. It could have been any disease, or any sort of tragic event that happens in your life. But being able to have the support of this person, my wife, and these people, these friends that I found, this family of musicians and people who love the songs. … That’s what I wanted it to say more than anything: That it was a great time. It was a great moment. It was a celebration.”

Escovedo’s voice sometimes suggests the drama of Nick Cave, or the left-field clarity of the best Bowie. There’s the wry edge of Elvis Costello. And the careful but muscular minor-key musical backdrops offer defiance, loss, and wisdom in equal measure.

Despite its back story, The Boxing Mirror isn’t remotely sentimental. Tough, honest, and lovely, it’s appropriately titled, with elements of both fight and reflection. On the opening track, the narrator separates his past and present selves: “I turned my back on me / And I faced the face of who I thought I was.”

Escovedo has made changes because of Hepatitis C, for instance giving up alcohol. He’s had to separate the lifestyle of being a working musician from the process of creating music. “I feel like a different person,” he said. “I feel like I’m more prepared to deal with whatever happens out here.”

Quitting drinking, he said, “helps me focus more on music. I feel like I’m more about being out here to play and constantly getting turned on by music than other things.”

One reason The Boxing Mirror doesn’t come off as cheap is because its words and music are appealingly elusive. Escovedo said the poetry of his wife, Kim Christoff, was a major influence, and her words are set to music on a handful of songs, including the phenomenal “Notes on Air,” a squealing rocker with its “truce made of rubber.”

“She’s truly a poet,” Escovedo said of Christoff. “I’m not a poet. I’m a songwriter. I believe that her words are much freer than mine – more open, and abstract I guess you could say. But there’s still deep emotional quality to the words.”

His own songs have grown less direct, he said. “Getting that close to the edge and then coming back, I think that gave me a perspective I obviously never would have had before,” he said. “The songs became a little more open-ended as far as imagery, and not trying to be so narrative.”

Yet “Died a Little Today” addresses Escovedo’s mortality head-on: “It’s a strange way we live / To have been here before / And leave nothing behind.” The implication is that Escovedo wants to make his mark, to leave something behind.

As his friends attest, he already has.

This article was originally published in slightly different form in the River Cities’ Reader.