Today marks the release of Brian De Palma’s adaptation of The Black Dahlia, and I’m torn.

Today marks the release of Brian De Palma’s adaptation of The Black Dahlia, and I’m torn.

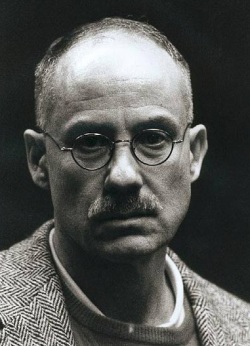

- I love the work of James Ellroy – the crime writer on whose novel the movie is based.

- De Palma does virtually nothing for me.

- Ellroy has gotten more stylized, more sophisticated, and better over time, and 1987’s The Black Dahlia – the first book of his “L.A. Quartet” that closed with the fantastic L.A. Confidential and White Jazz – began a period of rapid growth. That’s a nice way of saying that the book is lesser Ellroy.

- Yet Matt Zoller Seitz is persuasive about the movie’s charms.

- And then Dana Stevens guts it.

Of course, Ellroy and De Palma are a natural pairing. Two polarizing, masturbatory bullshit artists who pay inordinate attention to surface. Two guys with an unhealthy thing for violence against women. Two calculating technical masters who seemingly manipulate audiences with ease. The Black Dahlia is bound to be brilliant or a disaster. Or both.

The challenge in evaluating Ellroy is that it’s impossible to tell if he’s ever being serious. The self-anointed “demon dog of American crime fiction,” he is a bully nonpareil. The introduction to a new interview at GreenCine nails the effect of the author’s aggressive, frothing manner:

“James Ellroy is an enigma wrapped in confident, arrow-direct statements. He’s unerringly polite, remembers your name, and it seems like he’s telling you the unadulterated, bullshit-free truth the whole time, but all along you know that you’ll be printing exactly what he wants you to – no more, no less. You’re a reader looking at a character in one of his books while he, the author, tells you exactly what to think about them. Does he really like the film adaptations of his novels L.A. Confidential and The Black Dahlia? Who knows. Unsurprisingly, he wants people to read his books, so he’ll submit to the press engagements surrounding their release.”

Yet with eyes wide open, the interviewer then submits to Ellroy’s spell:

“But after a making a long career of it, he’s grown sick of profiting by his own mythology – his obsession with his mother’s unsolved 1958 murder, the 1947 murder nearby of Elizabeth Short, dubbed the ‘Black Dahlia,’ and other unsolved murders of women.”

Given Ellroy’s peerless self-promoting, I’ll believe that when I see it.

(People interested in the marriage of Ellroy and De Palma would do well to start with these collected links at GreenCine Daily.)