To discuss Michael Haneke’s much-praised Caché is to rob it of something that seems essential. In introducing the movie, you need to start with the opening, but describing that shot means that the reader won’t have the experience of seeing it fresh, of being confused and baffled and frustrated by it.

To discuss Michael Haneke’s much-praised Caché is to rob it of something that seems essential. In introducing the movie, you need to start with the opening, but describing that shot means that the reader won’t have the experience of seeing it fresh, of being confused and baffled and frustrated by it.

Being the kind sort, I don’t want you to be confused, baffled, or frustrated. I want you to be enlightened. So if you wish to be spoiled (enlightenment is in no way guaranteed), read on. If you prefer to be confused, baffled, and frustrated, go into the movie blind.

What’s unfortunate (or very, very clever) about Caché is that Haneke has created a movie that requires such intensive decoding at its terminals that it’s easy to overlook the rest of the movie – to, in fact, miss its entire point. By spending so much time and effort on the beginning and the ending, we neglect essential questions: What is the film trying to say? Is this an effective way to communicate that message?

Writers better than I have used words such as “bourgeois” and “diegesis” to explain Caché on psychological and political levels. Those elements certainly exist, but they’re lost in the movie’s self-satisfied trickery. The film’s difficulty, and the teasing way it flirts with a plausible solution to its mystery, undermine its obvious core purpose.

1. The Beginning

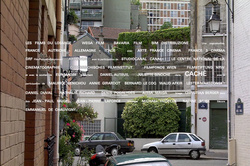

The opening shot of Caché lasts for more than three minutes. It shows a residential neighborhood, and the camera does not move or in any way reveal what you’re supposed to pay attention to. The three-dimensional reality of the depicted space is several blocks deep, but as a two-dimensional image it’s densely cluttered, compressed; the eye roams, looking for something to watch. As a viewer, you’re uneasy, because you fear that by searching you’re missing something important.

The opening credits roll out on top of this image. They are not presented in the traditional way – one after the other – but as a mass of barely differentiated text. Again, the person watching the movie is unsettled, unable to focus and feeling stupid for it.

And that is the effect for which Haneke strives. He wants you to be just like his main characters, Georges (Daniel Auteuil) and Anne (Juliette Binoche). They are married and have a sullen teenage son (more on him in a bit), and they are watching what the movie’s audience is watching. And they are confused, baffled, and frustrated by it. This is a videotape that was left for them in front of their door.

They are also scared, because the videotape shows their home. It’s right there behind that big bush, not quite centered, about three-quarters the way down the frame. Take a look at the first picture. There’s a woman leaving the house, behind the gate to the left of the bush. That’s Anne.

So that’s the opening shot, and the movie’s central mystery. Who made the tape? And why?

Initially, Caché appears to be a commentary on surveillance culture, a world in which our lives are recorded in minute detail by cameras, through financial transactions, and through the digital crumbs we leave virtually wherever we go. Privacy, the movie seems to claim, no longer exists.

Yet it does. The sheer volume of information that we leave means that we remain hidden, like any one person in that glut of opening credits, or like any particular detail in that opening shot. There’s too much undifferentiated stuff to feel like we’re being meaningfully monitored.

Yet it does. The sheer volume of information that we leave means that we remain hidden, like any one person in that glut of opening credits, or like any particular detail in that opening shot. There’s too much undifferentiated stuff to feel like we’re being meaningfully monitored.

Unless, of course, somebody targets you. What’s chilling about Caché is the idea that somebody would have the skill, time, money, access, and motivation to collect that information about an individual.

2. The Ending

To talk about Caché, one must also deal with the closing shot, which lasts more than four minutes. The closing credits roll over it, giving the false impression that there’s nothing to see here, unless you’re the type of person who waits to see if even arty foreign films offer parting gag reels.

The helpful critic must plant the seed that the reader should pay particular attention to this final shot, perhaps even pointing out where on the screen they should look. Something does happen. Watch for that sullen teenage boy. To whom is he talking? Not the group of friends with whom he exits the school, but the person who walks up to him, chats with him, and leaves.

The helpful critic must plant the seed that the reader should pay particular attention to this final shot, perhaps even pointing out where on the screen they should look. Something does happen. Watch for that sullen teenage boy. To whom is he talking? Not the group of friends with whom he exits the school, but the person who walks up to him, chats with him, and leaves.

Surely, sullen boy doesn’t know that person, does he?

And does that mean that … ?

Give Haneke credit: What he does with the movie’s final shot is tantalizing.

But it’s also meaningless, because the audience is left with incomplete information. Hell, the audience is left with virtually no information, merely the evidence that on this particular day, these two people seemed to be acquaintances.

How disparate are the potential reasonable readings?

- Sullen boy and the other person are conspirators.

- Sullen boy and the other person are merely friendly with each other, suggesting that the sins of the father do not stain the son.

- Sullen boy is being photographed, just like his father.

The truth, you see, is hidden. Deep, huh?

3. The Middle

The genius of Haneke’s conceit is that the surveillance of Georges and Anne is so … ordinary. He has tapped into the reality that a person targeting you wouldn’t actually need skill, time, money, or access to spook the shit out of you. All they’d need to do is provide evidence that you specifically are being watched. For example: by pointing a video camera at the front of your house and leaving the videotape on your doorstep.

This simple and inexpensive act has the power to unlock deep paranoia. Caché haunts the audience because it initially shows how something so fundamentally benign can unravel us.

The tape inspires in Georges guilt, as he goes through in his head a list of all those he has wronged. He quickly settles on a childhood acquaintance as the suspect with the best motive.

This is a perfectly reasonable process, but Haneke gooses it: Georges is pushed toward his conclusion by new videotapes that arrive on his doorstep. One shows his childhood home. Another reveals the location of an apartment. They are wrapped in ghoulish but youthfully crude drawings. Georges’ tormentor, it would appear, doesn’t merely want to unsettle our protagonist; he seems to be leading him toward a confrontation with his past.

Caché here starts to leach its potential as an expression of common anxiety in the new millennium. Haneke doesn’t trust his own elegance, and replaces effectively anonymous surveillance with s

omething personal.

While the first tape was upsetting mostly because virtually anybody could have created it, these later tapes and their wrappers require an intimate knowledge of Georges’ life. In fact, there are only two people with the information the deliveries would seem to require: Georges, and the young Algerian his family took in.

What’s intentionally maddening about this path is that neither alternative seems likely. Caché is far too grounded and restrained to invoke the literal, gothic dualities of Poe’s “William Wilson” or Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. And it’s evident to all but Georges that the feeble man he knew as a child is incapable – temperamentally or technologically – of making the tapes. (He is capable of causing great harm, but it’s of a different sort.)

The movie’s ending suggests a third alternative, but there’s no apparent motive for such an elaborate – and mean – trick, and the knowledge required seems too shameful (on both ends) to be passed down to the younger generation.

All three possible explanations are plausible. None is plausible enough.

And so Haneke leaves us with … nothing?

4. The Pointlessness of It All

Does it matter from where or whom the tapes come?

As one blogger wrote:

“Like all the great Hitchcock films, these videotapes are a MacGuffin and are pretty inconsequential in terms of what the film is actually ‘about.'”

Fair enough, but that explanation seems counterintuitive. If the tapes are merely meant to get the plot rolling, why does Haneke emphasize them so, from the first shot through the last, and in the way the entire movie is photographed?

As Wikipedia notes in its entry on the MacGuffin:

“Commonly, though not always, the MacGuffin is the central focus of the film in the first act, and then declines in significance as the struggles and motivations of the characters take center stage.”

This clearly doesn’t happen in Caché. The author of the tapes remains the central concern of the film through its final moment. Most of the discussion of the movie unsurprisingly focuses on the ending.

Yet Haneke’s agenda is much larger than the tapes. Obviously, Caché is meant to operate in part as metaphor. Georges represents the French, and the Algerian represents, well, Algerians living in Paris. The guilt Georges feels represents the guilt of the French people for the Paris massacre of 1961. Haneke makes the connection explicit, as the Algerian boy’s parents died in the event, and Georges’ family planned to adopt him.

A simplistic reading would suggest that the French deserve to be reminded (through the tape) of the massacre – that the guilt is warranted, and that adequate amends have not been made. A more nuanced (and not necessarily incompatible) interpretation says that current French foreign policy toward Algieria (in the form of Georges’ bad behavior toward the Algerian) is poisoned by this unallayed guilt. (Full disclosure: I know nothing of French domestic or foreign policy then or now.)

Setting aside the strangeness of a German pot (that would be Haneke) faulting the French kettle for a mid-20th Century atrocity, this still gets us no closer to understanding the source of the tape. The blunt politics might make Caché more resonant and pointed, particularly for French audiences, but it doesn’t illuminate the mystery, or even fit with it.

The film’s fixation on the tapes could be justified if the lack of resolution dovetailed with its themes, or even if the impossibility of a definitive (or merely probable) solution were confirmed. But the film is not nearly so agnostic.

If the movie were about the impossibility of knowing, or the elusiveness of truth, it might make sense for the mystery to remain intact. But the movie is fundamentally about guilt and the way it makes people behave. Georges does withhold information from his wife, but outside of the tapes’ source, the audience is given relatively full information whose veracity is never cast into doubt.

The emphasis on the opening and closing shots detracts attention from the themes and points Haneke clearly wants to stress. And because the writer/director continually suggests that you can solve this mystery – if only you pay close enough attention – he regularly distracts the audience from his message.

The tapes are superfluous. So what does it say about a movie when the MacGuffin captures the audience’s imagination far more than the film’s serious themes? Caché is so in love with its formal brilliance and cleverness that it forgets what it’s about.

I found myself examining the opening shot of Cache as you pointed out all over because it demanded that. With a title like Cache one supposes that in this shot there must be something to find. I later determined that this shot’s intention, as with the other shots like this one in the movie, was to establish the viewer’s acknowledgment of the boundaries of the screen. A difference between theatre and film is that, in most cases, the proscenium determines the boundaries of theatrical stage and remains fixed and players move with in the stage space. The audience is free to look where they want within this space. In film this is less the case with the camera doing most of this work for the viewer in terms of where to look. Haneke in these shots is blurring the boundary between the stage and the screen. Haneke’s work often deals with the relationship between itself and the audience. Look at ‘Funny Games’ and the way a central character in that film ‘breaks the fourth wall’, directly addressing the audience.

That the mystery remains unsolved is one way the director is activating discussion to determine the movie’s outcome or meaning. In Cache everything remains hidden and there are a coupe of scenes that directly deal with this idea that have no bearing on the movie (ie the part with the cyclist riding the wrong way down a street).

For me this film was a formal exercise dealing with how we look at things like a film screen and expect to be dictated to and given meaning by a work of art rather determining our own. I thought that Georges issues of guilt as a metaphor surrounding Algerian massacre was present as an aspect of the film, but lost behind the movie’s formal aspects- hidden i suppose. And that is the brilliance of the film- that it has layers and demands or needs a range of interpretations, but doesn’t end up saying nothing in the process.

To the author of this article/critique: Your writing is fantastic. This is by far the most satisfying thing I’ve yet read on the movie.

Thank you SO much for being CLEAR! And thank you for not being self-involved! You are one of the few people I’ve seen on the internet who isn’t intimidated by the intense (and to me, contrived) “suggestiveness” of the film – which appears to make most viewers worry that they’re missing the artistic boat. Like if they don’t find some grand reason or message which “justifies” Haneke’s film, somebody else will. And god forbid, that would make them appear not to have this situation under control.

I think your final sentence absolutely nails it. I have to ask myself why Haneke wants to instigate people to pontificate about the film’s meaning. It is brilliantly engineered to bring out that quality in humans! We KNOW (enough) people love doing it. And nobody who does it admits it – especially to themselves, I swear… You put yourself across extremely well – more calmly & intelligently than I would have – in an ocean of intellectually frightened bullshitters. Go Jeff!

That was a very interesting commentary on Cache, although to me, the point of the static shots begining and ending have more to do with being symbols of observation which are available to everyone. You can pretty much examine whatever or whoever you want, but mostly we choose not to examine much, especially ourselves or what appears to be obvious, such as the apparently successful lives of Georges, Anne, and their son. Examining Georges and Anne’s lives is pretty revealing, not just in the guilt about an occurrence in Georges’ live when he was six, but in the family’s current situation. I thought the couple’s relationship was very cold and borderline hostile. They just barely got along. Their son was obviously a huge presence in their lives, but absent a lot, and they often didn’t know where he was. AND they didn’t know much about what he was thinking. Was he the one videotaping? To uncover what he believed to be an affair between his mother and the friend Pierrre? I felt the surface of their life was very flat and superficial – what was going on underneath was hidden. Do they love each other? Do they even like each other? They never once said a nice or understanding or supportive word to each other. Was she having an affair with Pierre? Was she feeling guilty too? I don’t think who made the videotapes was important, only that anyone could take a closer look at them and discover that who they really were was hidden. They seemed to be living such a normal existence; just taking a surface look says that they are successful, happy, prosperous, etc., but this one thing uncovered an empty, unhappy relationship criss-crossed with guilt, ignorance, defensiveness, fear. The end for Georges, when he goes to bed in the middle of the day, closing all the curtains and crawling under the covers, with all the dull blues, was of a pathetic, beaten man.

Susan: I like your reading, particularly the point that “we choose not to examine much.” And I like your attention to family life, which seems to me more mundane but also more interesting than the political stuff here.

But I’m still troubled by Haneke’s coyness, and the opacity of the movie. I like movies that craft a sense of mystery and liquidity, but Cach – is too nebulous by half. There’s so much – and so little – there that it means whatever you want it to me, which is a cop out.

I just watched the film. I enjoyed it and am steeped in the mystery. There are scenes, like the tape from Majid’s home, that I find hard to believe was set up by Georges’s son. How could he have placed it so well, and knew his father was arriving when he did? And the footage from the vehicle passing Georges’s mother’s home. He doesn’t drive. But perhaps Majid’s son does. But do either know where it is? Do either know about Majid coughing up blood as a child, or killing the rooster?

The problem, of course, is that there IS no explanation that is “true.” The reason for this is that, as a work of fiction, there is no answer except those that are shown or implied by the author. That explanation would be manifest on the screen. I mean, if I had made this film (as is) but the “answer” was known only to me, and I hadn’t actually filmed anything that would betray the truth, then where is that information “in the film”? The film is not real. We invest emotions and intentions in the characters, but they are simply the emotions and intentions of the author and director (and actors I suppose) pulling each other’s strings (in this case also pulling ours).

If this were a documentary, we could say there is an answer “out there” that needs to be uncovered. The “answer” to this film lies outside the film, which is to say outside the universe of the film. The director could say a person who likes salmon mousse did all the tapings. So what? What does that explanation have to do with the film? Does it matter if he had this explanation in his mind during the film, or made it up after the fact to play with us?

The truth is Haneke has dreamed up these videos to confound the characters in the film and us watching it. The film, too, is a video. Who made it, and why? And isn’t Haneke also “on film” giving his coy non-explanations of the film? For whose benefit is all of this, and what do we get out of it? The director?

In order to determine who provided the tapes, let’s determine how Majid’s son manage to attend the same school as Georges’ son? Wouldn’t the son of a successful television host attend private school? Majid’s son doesn’t fit the demographics of the student body — did he gain admittance due to scholarship and hard work? If so, what does that reveal about Majid’s intelligence? Does his placement and academic success extend to having a strong character? A sense of empathy, justice, respect, loyalty and love for his hardworking father?

At their first encounter, Majid told Georges that he had recognized Georges on his television program several years ago. Wouldn’t any person/father boast about his childhood connection with a popular television host? Did this produce a father/son conversation about Majid’s past, including the turn of events, the pain of rejection, his orphanage experiences, loss of family, etc. If the two boys attended the same school, shouldn’t Majid’s son recognize (by name?) Georges’ son and relay their coincidental connection?

Why was Georges’ son featured minimally in the story? Most scenes include only Georges/Anne; some show their relationships with friends/coworkers. Aside from the opening meal scene and the swim meet, when do the three act as a family? Suspicion of the kidnapping allowed for our second encounter with Majid (and introduction to Majid’s son), but if he isn’t the answer to the big question, why even bother featuring him in the film at all? (I saw so little of their son I kept wondering if there was a stepparent that was housing the kid.)

Watching one’s parents live in fear would be a passive/aggressive, yet ever-so-satisfying way to get even for the neglect and anger this kid is feeling. The two boys conspired to terrorize Georges with information only Majid would have shared with his son. Each boy has their own motive for making the tapes.

Because George does film editing at work, it’s possible some of his technical knowledge (including editing) was passed on to his son. Majid’s son is considerably older (and taller) than Georges’ son, likely of driving age, capable of filming the scenes away from residence, including the POV needed to film the height identifying Majid’s apartment number.

I watched this movie with my hubby last night, five years after watching it the first time (by myself). There’s nothing more frustrating than spending 2 hrs on a movie and feeling confused with no one to point out the details that are missed the first time around. My hubby expressed the same boredom and confusion I had five years earlier. This time around I enjoyed the film knowing the ending school scene held a clue to the mystery.

Problems I had with the film: If Majid wasn’t part of the taping, it’s unlikely a small apt could hide a functioning video camera. BUT – there was a time when cameras were able to film babysitters abusing their charges — maybe these cameras are activated when motion is detected? Also, why would Majid close the door (twice) to the room in his apartment that Georges and he have their conversations — the second time for the blood to spray effectively?

(I enjoyed the mirrored elevator scene — which occupant on the elevator was the cameraman?)

Sharon Winters

Fantastic review. Would like to also add I’m unsure that examining the concept of guilt is best achieved through the actions of a six year old boy, and I agree with Georges who feels he has nothing to feel guilty about. Further, I also get the impression Haneke, in trying to be too clever by half, himself has no clear view as to the denoument: now I understand about leaving things open ended, but look how much better David Lynch does that in Mulholland drive. The ending of Cache just drifted into disparateness which detracts from the focal points which as Haneke says, are about morality.

In the interview on the DVD of Cache, Michael Haneke says, “The movie is a tale of morality, so to speak, dealing with how one lives with guilt…That’s basically the theme of the movie.” This agrees with the reviewer who says, “…the movie is fundamentally about guilt and the way it makes people behave.” But it is not actual guilt, but the feeling of guilt, that is at issue, for, as Haneke notes, a child is not guilty for his selfishness even though an adult would be. However, he can be guilty as an adult for how he behaves in light of his memory of doing something that destroyed another person’s life, and the film is partly about that actual guilt. Haneke thinks it is unclear what the events were that got Majid sent away to the orphanage. But the scene at 20:39 (called “the smoking gun” by Roger Ebert) of a young Majid bleeding from the mouth and holding a pill in his hands suggests that Georges gave him something that made him bleed internally. According to what Georges tells his wife Anne, they did call the doctor to look at Majid, but he was such an old fool that he didn’t think anything was really wrong. So Majid was not sent off to the hospital. But then it seems that Georges might have got Majid to chop off the head of a rooster by telling him that his father wanted that and then telling his parents that Majid tried to hit him with the ax. The two flashbacks or dreams of those scenes give us reason to think that Georges did something to get Majid out of the house so he could maintain his privileged position. The evidence presented at least allows us to construct a plausible story of why Georges feels guilty about his treatment of Majid when they were children.

In an interview in 2009 on indieWIRE, Haneke says, “These questions, ‘What is reality?’ and ‘What is reality in a movie?’ are a main part of my work.” So I think the question of what reality is in Cache is also an important focus of the film. While neither the viewer, nor the characters in the film, know who made the tapes, surely someone in the fictional reality, the world of the film, did somehow make the tapes. There must be some truth about who made the tapes and why. That’s why Haneke seems unjustified in saying in the DVD interview that, “We never ever know what is truth. There are 1,000 truths. It’s a matter of perspective.” Whether in the world of the film, or in reality, there are not 1,000 truths on a given question, even if there are a 1,000 beliefs about what the truth is. Further, it is an unwarranted leap to conclude that “we never ever know what is truth” just because sometimes we do not know what the truth is. We are not justified in reaching that conclusion in either the film world, nor in the reality, on the basis of sometimes being ignorant of what the truth is.

I recently saw “The White Ribbon”, also by Hanneke. After it ended, I felt more and more annoyed at having been manipulated (and bored!). I remembered disliking “Hidden” even more, and so I have just now gone back to read different reviews. While so many reviewers loved the intellectuality of “Hidden”, I am heartily reassured to see your very accurate review here. Thank you for articulating clearly some of what is wrong with this film. My own view is that Hanneke is politically driven (small p large P – that part is immaterial). While many of his political views are worthy, one is that likely members of his audience should feel bad for various attitudes they have. Including wanting to be entertained by a film. As one of the people funding his work, I think this is breath-taking arrogance.

The person who took the videos is Michael Haneke.

While Cache certainly has layers regarding how people react to paranoia and guilt and one cannot help but wonder what the connection at the end of the movie is between Pierrot and Majid’s son, ultimately if one looks at the film simply, there seems only one logical explanation and that is that Majid was the person who did the taping. He was clearly unhappy in his life and clearly unstable – did he just spontaneously decide to kill himself because George mysteriously showed up in his life – someone taped them in his apartment and his son does not seem to be unstable nor filled with anger – he is the most unstable person in the movie whose ultimate act is wildly unexpected and inexplicable – just as the tapes are unexpected and inexplicable. His unhappiness certainly adds depth to the question of how tragic his life was and how his life was deprived of the opportunities he could have had were it not for the jealousy of a 6 year old boy who contrived a lie that ultimately tore him away from an easier life. This unhappiness has festered in him. My own opinion is that he did not have a grand plan – he just set out to unsettle Georges. It set in motion the events that followed resulting in Majid and his son being held in jail overnight for something they clearly had no part in – adding to his bitterness and instability. I think he simply decided to have Georges come over and to kill himself in front of him because his despair at the racial divide and unfairness of his circumstances overwhelmed him. To me the beauty of this film is the ordinariness of it all and how banal choices can have tragic and unexpected consequences. There does not seem a need to over analyze the political overtones – they are extant in the time and place of the film – nor do we need to analyze Majid’s son and Pierrot’s scene at the end of the movie – they are a new generation which does not carry the same bitterness and guilt carried by their fathers, but they are now bound by that tragedy – the only twist there would be if we are to suppose that Majid’s son will take out his revenge by insinuating himself into Pierrot’s life – but that would be inconsistent with how he has been presented. Sometimes a really good film is just a really good film and does not need to be so over-analyzed.

If you watch carefully you are in fact told who sent the letters and such / inside of the first 25 min you know pay attention to dialogue.