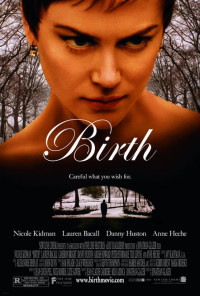

Birth

Birth is the perfect antidote for anybody who thinks reincarnation is a romantic notion, allowing for a reunion with the spirit of a loved one who has died. The movie, co-written and directed by Jonathan Glazer (Sexy Beast), gives the audience a worst-case scenario for reincarnation: A widow, on the eve of getting married again, is confronted with a dead-eyed, flat-voiced twerp claiming to be her deceased husband.

Birth is the perfect antidote for anybody who thinks reincarnation is a romantic notion, allowing for a reunion with the spirit of a loved one who has died. The movie, co-written and directed by Jonathan Glazer (Sexy Beast), gives the audience a worst-case scenario for reincarnation: A widow, on the eve of getting married again, is confronted with a dead-eyed, flat-voiced twerp claiming to be her deceased husband.

By mining the practicalities of the situation, the movie becomes a rare work that humanizes and seeks to understand the effects of reincarnation instead of merely employing it for cheap horror or cheesy romance. And unlike The Village, Birth is genuinely interested in probing the ramifications of its conceit. After seeing it, you’re likely to want the dead to stay in their coffins, and their souls to keep to themselves instead of meddling in the business of the living.

The finely crafted movie is a tough sell: patient, chilly, emotionally guarded, visually dark, and completely averse to giving the audience a good time. It wants you to squirm, but its creepiness is not drawn from spectral presences. Although reincarnation is its hook, Birth is earthbound and carnal rather than spiritual. Fundamentally, it’s about nearly impossible choices.

What the hell are you supposed to do when the kid knows intimate details of your life and might just be your dead spouse? But knowing information doesn’t mean the brat has the emotional characteristics or the disposition of said husband, right? But how could you turn the boy away, if there’s even the possibility, however remote, that he’s your true love re-born?

And what about the fiancé? A decent man, no matter his skepticism, would understand the wrenching situation his future wife is in. Yet he’d be right to want to spank the little fucker – treating the boy, for the first time, like a child and not a miniature adult – for ruining his life and throwing a wrench into hers.

There’s no dank little corner of the issue that Birth doesn’t address. In an infamous scene, the naked scrawny boy gets into the bathtub with the woman, and the bit is striking not because it’s awkward or kiddie-pornish but because it isn’t; at that point in the movie, the premise is so disarmingly ingrained that the woman’s unfazed reaction – from her perspective, this intimacy is wholly natural – is matched by the audience’s.

That type of identification is a key to the movie’s success. There’s nothing distinctive or detailed about the engaged couple, and they serve primarily as vessels. The filmmakers seem to be asking: What would you do?

Nicole Kidman plays Anna, with a pixie haircut that immediately suggests vulnerability by sparking memories of Mia Farrow’s fragile Rosemary. Kidman was nominated for a Golden Globe, but the part mostly requires her to get sucked in. As fiancé Joseph, Danny Huston has a much more challenging task, needing to balance his character’s sympathy for Anna with an unwillingness to indulge her too much; he’s put in the difficult position in which he could lose her by being too sensitive or not sensitive enough, and his margin for error is tiny.

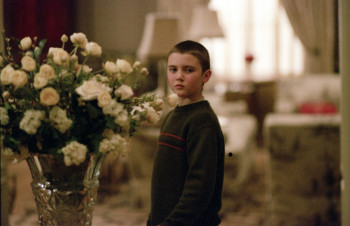

Cameron Bright brings an unremitting, clinical joylessness and seen-it-all impassivity to the part of the kid, Sean, but the decision to play the role coldly meshes well with Birth’s somber tone and has the added benefit of making the audience dislike him immediately and forever. It’s critical that Anna succumb to the idea of reincarnation instead of the charm, innocence, or cuteness of a child – none of which Sean has.

Nobody among the three main characters has as much character as a couple of bit players, Peter Storemare and an unrecognizable Anne Heche as estranged friends of Anna and her dead husband. They’re the only people in the movie who appear to have actually lived, and their worn and damaged surfaces are stark contrasts to the wealth- and privilege-conditioned veneers of Anna and Joseph. For that reason and because of narrative economy, it should come as no surprise that these fatigued souls play an essential role in Birth’s resolution.

The third act is certainly problematic, but there is simply no way to pull the narrative together in a satisfying way. In solving its central mystery, the movie twists itself into a messy knot of exposition, back story, and improbabilities. Is the reincarnation real or fabricated? You intuitively know the answer to that. The film strings viewers along with the tantalizing possibility of the supernatural, but it’s so grounded in the tangible that it’s nearly atheistic. How can you prove reincarnation to a skeptic?

Of course, audiences wouldn’t tolerate the alternative of leaving the reincarnation question open. And doing that would rob Birth of its rewarding, late-arriving psychological component, namely Sean’s obvious psychosis.

But all this ignores the point that the movie is not about reincarnation; Birth uses reincarnation as a metaphor for refusing to let go of the past. The movie delves so deeply into the issues it raises that there’s no looking back and no retreating. The damage is already done, and nothing could salvage the characters, no matter how that nagging narrative question is answered.

But ignore that the resolution steers the movie off-course. Birth is still quietly powerful – provocative in the best sense.