A submission to Counting Down the Zeroes, a project by Ibetolis at Film for the Soul.

Requiem for a Dream

My dictionary says a requiem is a musical composition or somber chant in honor of the dead, but Darren Aronofsky’s Requiem for a Dream is more like a howl of pain that builds slowly over 100 minutes to an intensity that’s nearly impossible to bear.

My dictionary says a requiem is a musical composition or somber chant in honor of the dead, but Darren Aronofsky’s Requiem for a Dream is more like a howl of pain that builds slowly over 100 minutes to an intensity that’s nearly impossible to bear.

The movie is anchored by a droning cello and mournful violins, mixed with techno elements in Clint Mansell’s haunting minimalist score. The music is insistent, anxious, and pervasive, and its prominence and repetition of motifs emphasize the emotional rather than intellectual or narrative character of the film.

In plot and texture, Requiem is an unrelentingly grim portrait of addiction that’s hard to endure, that’s furious and heavy-handed, and that’s after-school-special facile. Yet it comes from a well of deep, genuine love for humanity, a reservoir so full that the film becomes a sustained lament for the loss of four pathetic addicts who dream only of their next fix.

The movie is also tinged with a bitterness directed at an apathetic society that refuses to help these people before they’re so far gone that their lives cannot be salvaged. Count the number of missed opportunities for intervention, and note how many times people avert their gazes rather than confront the problems right in front of them. See one doctor who never makes eye contact with his patient, and watch another physician call the cops instead of helping a guy with a badly infected arm.

Aronofsky’s second feature, based on the book by Hubert Selby Jr., is also a stunning technical accomplishment. Variations on a series of rapid-fire images (a fixture of the director’s debut, Pi) capture the mechanics and feel of drug habits; a split-screen technique creates barriers between people only inches apart; cameras mounted to actors on special rigs make it impossible for these lost characters to escape the audience’s stares; and television images blend with real life in a surreal sequence of dementia.

Like no other movie except perhaps Magnolia, Requiem for a Dream confidently and successfully buries technical prowess and daring in a narrative so passionate that they’re easy to miss. The film feels raw but is actually meticulously planned, deliberately paced, and carefully executed.

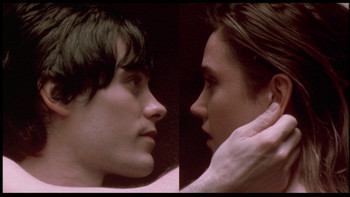

At the movie’s center is Harry (Jared Leto, in a beautifully natural performance). He “borrows” his mother’s television to get money for drugs. His girlfriend Marion (Jennifer Connelly, forced to endure trials that would make Lars von Trier proud) is also an addict, as is his best friend Tyrone (Marlon Wayans).

Harry’s mother, Sara Goldfarb (Ellen Burstyn), is a different sort of junkie. She loves the television, and dreams of being a celebrity, no matter how fleeting or small her fame might be. When she’s notified that she might be a contestant on a game show, she gets hooked on diet pills trying to lose enough weight to fit into the red dress she wore to Harry’s high-school graduation.

Whatever traditional dreams these characters might have had died long before the movie begins, and their lives at Requiem’s start are already bereft of joy or meaning. Yet these folks grab you. In a different movie, they’d be cold and remote, but Aronofsky and his cast pull off a minor miracle by creating people who are soft, open, and vulnerable; they have shockingly modest aspirations that deep down they recognize as unattainable, and their sadness and emptiness are palpable and heartbreaking.

It’s easy to read the movie as a screed against drugs, but that characterization doesn’t fit. Aronofsky balances natural if extreme consequences of addiction with some of best visual representations of first-rush pleasure you’ll ever see; in that way, the movie understands both the allure of drugs and the damage they cause.

But the movie’s scope is too narrow to say anything interesting or meaningful about drugs. In the end, it’s not even remotely political. Like Tyrone, jailed and frightened as the movie closes, Requiem for a Dream is simply screaming for somebody to pay attention.

Loved this essay about Requiem. Thank you very much! I love your website!

Gina Marie

The mark of a good critic is to know that being critical doesn’t always require you to criticize. Calling the movie narrow in scope without backing it up by citing specific examples is at best overdone and at the worst not even done well. People aren’t getting smarter, they are just becoming more opinionated. I am tired of reading blogs claiming to be reviews but instead are only a laundry list of opinions. Trying to stand out by being the voice of dissent in the review of a movie that is highly praised by both critics and fans alike is not anything new. But being bad at it seems to be getting old. “Narrowness of Scope” ??!!?? Yes the film does lack the other side of the spectrum: “The happy well adjusted drug addict.” This film may be fiction but its not fantasy.

Sonartina: (1) Saying the movie in narrow in scope is not a criticism. Generally speaking, I don’t want movies to aspire to social commentary; generally speaking, they’re terrible at it. (2) “Narrow in scope” is another way of saying it’s specific. That is a high compliment from me, not merely “not a criticism.” (3) If we’re demanding support for our positions, how exactly is Requiem for a Dream not narrow in scope? I didn’t support that assertion because it seems to me self-evident. The movie is about a handful of well defined characters much more than it’s about drugs; it’s about drugs only to the extent that these case studies feel authentic. (4) I find it hilarious that you somehow believe I don’t like this movie. (5) I find it hilarious that you somehow believe a broader scope would involve “the happy well adjusted drug addict.”