The Dancer Upstairs

Narrative economy is a great thing in most movies, but with thrillers and mysteries, it can have a serious downside. If a script and movie are tight, each character or line of dialogue is important. The corollary: The detail or character that seems most insignificant shall inevitably play a critical role.

Narrative economy is a great thing in most movies, but with thrillers and mysteries, it can have a serious downside. If a script and movie are tight, each character or line of dialogue is important. The corollary: The detail or character that seems most insignificant shall inevitably play a critical role.

And so it is with The Dancer Upstairs, John Malkovich’s assured but cautious debut as a film director. The “twist” is evident at least an hour before it’s fully revealed, and at most points in the movie, the audience is a few steps (or miles) ahead of the characters.

In the end, there’s much to like about the film, written by Nicholas Shakespeare and based on his novel. But something isn’t right, nagging and prodding and saying that the movie isn’t all it might have been. It’s intelligent but not sharp, subtle in small moments but clunky overall, engaging without being engrossing, and sad but not heartbreaking. It’s as if there’s a layer of mist over the movie, dulling it, and that’s caused by Malkovich’s over-deliberate approach.

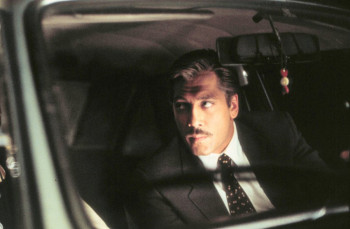

Javier Bardem stars as Augustin, a detective in a Latin American country. He was once a lawyer but became a police officer to “find a more honest way of practicing the law.” In the movie’s prologue, he’s a roadblock cop who lets a man go even though he could have been detained for not having the proper paperwork. Five years later, Augustin has been promoted, and he’s assigned to the case of a mysterious terrorist called Ezequiel, who has a devoted following that is executing seemingly random anti-establishment attacks all over the country.

Javier Bardem stars as Augustin, a detective in a Latin American country. He was once a lawyer but became a police officer to “find a more honest way of practicing the law.” In the movie’s prologue, he’s a roadblock cop who lets a man go even though he could have been detained for not having the proper paperwork. Five years later, Augustin has been promoted, and he’s assigned to the case of a mysterious terrorist called Ezequiel, who has a devoted following that is executing seemingly random anti-establishment attacks all over the country.

Of course, Ezequiel turns out to be the same man that Augustin stopped five years earlier, because, well, because that’s the way it is when a script and film are this obviously efficient. Each scene, each shot, has a single, specific, and obvious narrative purpose, and this lack of depth and texture makes it easy to figure out where things are headed and what they mean. To cite one example, if Malkovich shows you characters you don’t recognize, you know they’re going to get killed gruesomely in a matter of seconds. The audience is as a result prepared for bursts of violence that should be sudden and shocking.

Augustin’s investigation is slow and produces little information, and while he’s dawdling, seemingly waiting for a clue to present itself, he strikes up a flirty friendship with his daughter’s ballet teacher, Yolanda (Laura Morante). She doesn’t know he’s a cop – it’s something of a secret – and she’s so pleasant and pretty and innocuous and out-of-place in the movie that the audience knows something else is going on.

Augustin’s investigation is slow and produces little information, and while he’s dawdling, seemingly waiting for a clue to present itself, he strikes up a flirty friendship with his daughter’s ballet teacher, Yolanda (Laura Morante). She doesn’t know he’s a cop – it’s something of a secret – and she’s so pleasant and pretty and innocuous and out-of-place in the movie that the audience knows something else is going on.

This obviousness seems at least partly intentional, though. Take the misleading title: There is, as far as I can surmise, no dancer upstairs, but the non-article words considered separately become meaningful. And there’s a conversation in a coffee shop, in which Augustin and Yolanda try to guess the occupations/fates of people whose photographs decorate the walls. Their conclusion: Surface is deceiving.

So the viewer is always ahead of the characters, and there’s no surprise in the surprise. That creates a kind of suspense, of the “Come on, you idiot!” variety. The audience likes Augustin but wants him to be more alert, and more alive.

Bardem plays the detective sleepily, and he seems to conduct his work and marriage as matters of routine rather than passion. He is vaguely dissatisfied at home, casually involved in his job, and mildly irritated at the government for taking his father’s coffee farm. He gets angry only when the martial law is declared and the military is taking his kid’s drawings off the wall. He seems scared and rattled only once, when he gets shot at unexpectedly.

He remains a foggy cipher, and that’s a good description for the entire movie.

What Malkovich and Shakespeare get right is the delicate balance between the micro and macro, the personal and the political.

What Malkovich and Shakespeare get right is the delicate balance between the micro and macro, the personal and the political.

That counts for a lot, but I wanted more. Malkovich’s filmmaking style seems to draw from his acting – measured, clearly articulated, and a touch too precise. There’s nothing wrong with that, until one considers the subject matter of The Dancer Upstairs: terrorism, a mysterious and diffuse revolutionary group, a reactionary government; the movie feels far too calculated. What it needs – what it’s begging for – is some chaos, some messiness that shows the narrative has a beating heart in its chest and blood in its veins, rather than just a brain in its head.

A Political Aside

Like Roman Polanski’s Death and the Maiden (and the play on which that was based), Malkovich’s movie is set in an unnamed Hispanic country yet performed in English and clearly intended for an American audience. The specifics of the plots wouldn’t translate to the United States, of course, but certainly the themes of terrorism, tyranny, and the corruption of the justice system should be as resonant here as they are in foreign countries.

How different, really, is Ezequiel from the Unabomber, or Timothy McVeigh, writ large? And if you think the United States is devoid of corruption or extremism in its halls of power, please, please, continue to live your fantasy. This country, since the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, has willingly – even enthusiastically – given itself over to policies leaning toward totalitarianism in the name of national security. Martial law might be a stretch, but not by much.

Setting the stories elsewhere gives them a foreignness – “Oh, that couldn’t happen here” – that distances them from the politics of the United States. On the one hand, I find this cowardly and timid, because both works would be startling and provocative if given the setting of their primary consumption. But I also understand it, because the production and distribution system in this country is so scared of controversy and genuine politics that the movies would have been viewed as incendiary, and probably would never have been made.