(A contribution to The House Next Door’s Close-Up Blog-a-thon.)

Stripping Funny Games

Writer/director Michael Haneke’s 1997 film Funny Games feels like a response to something that hadn’t happened yet. Sure, we’d had Natural Born Killers and other ultra-violent movies, but the fetishism of agony hadn’t yet become a crass trend.

The prospect of Haneke’s English-language remake – due in theaters in late winter and starring Naomi Watts and Tim Roth – is worrisome. (George Sluizer’s American botch of his own The Vanishing comes to mind.) But it’s also necessary; as unpleasant as it is, Funny Games deserves to be seen more widely because it forces introspection. I doubt you can watch it without seriously considering why you watch movies of this sort, and how you react to them.

And it’s more timely now than it was upon its initial release a decade ago.

For me, the film is most striking in the scene in which Anna (Susanne Lothar) is forced by white-clad, white-gloved psychopathic visitors Peter and Paul to remove her clothes, while her helpless husband (The Lives of Others’ Ulrich Mühe) casts his eyes down and her young son sits on a couch with a bag over his head. (If you’re unfamiliar with Funny Games, this description is probably a truer representation than a plot summary.)

The scene is brutal, but its effects are achieved quietly, and the damage is purely psychological.

Haneke presents the action (in a little more than a minute) without words through a series of close-ups of faces, primarily Anna’s.

Most obviously, Haneke is frustrating the viewer expectation of nudity. There’s even a bit of a tease when Anna leans forward and the camera offers a promise of cleavage that it doesn’t keep.

By showing Anna’s body only from the shoulders up, he’s drawing attention to what he’s not letting you see. This is reinforced by a shot of the son, who sits in for the audience in this situation, his eyes covered. (There’s something comical in theory about a series of reaction shots that includes a kid who can’t watch what’s happening. But this is Funny Games, so it’s not really funny at all.)

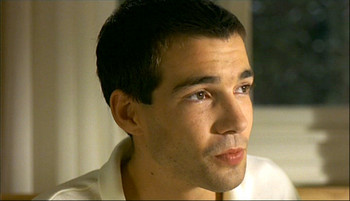

More importantly, Haneke’s technique ensures that the audience confronts the true impact. Look at the eyes of Anna and her husband, and contrast them with the coolness of Paul’s expression, and the anticipation and excitement of Peter.

There is devastation and loss and shame and grief in those victims’ faces, and although the scene isn’t physically violent, it might as well be for the pain it causes.

And, by coincidence, there’s this. (Via The House Next Door.)