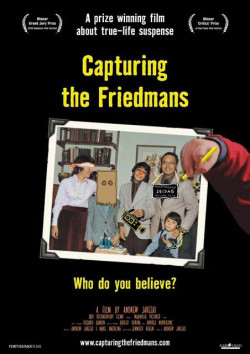

Capturing the Friedmans

Small things grab my attention in movies, and frequently I latch on to bits that are of interest to nobody but me. As a result, I often skip over or ignore the issues that grip normal people. I’m guessing that’s the case with Capturing the Friedmans.

Small things grab my attention in movies, and frequently I latch on to bits that are of interest to nobody but me. As a result, I often skip over or ignore the issues that grip normal people. I’m guessing that’s the case with Capturing the Friedmans.

If you tell somebody you’ve seen Andrew Jarecki’s documentary, those who’ve also watched it inevitably ask: Do you think they’re guilty? “They” are Arnold and Jesse Friedman, a father and son who were accused – following a 1987 police raid for kiddie porn – of molesting dozens of boys at computer classes they held at their home. Jarecki’s film uses interviews and a jaw-dropping number of home movies to present the Friedman clan, people so comfortable around the camera that they appear to have virtually no shame or shield.

Did they do it? The movie is wonderfully rich, and of all the things in it, this is among the least rewarding lines of inquiry for me. The most obvious point of the film is that we cannot know the truth of the accusations, so why argue about it? Most people probably come away from Capturing the Friedmans feeling that Arnold – an admitted pedophile – molested some boys in his home (he denies it), and that Jesse was wrongfully accused. (But if Arnold is guilty, wouldn’t Jesse – who helped teach the classes – know about it, and wouldn’t he therefore be complicit?)

A number of other factors complicate the quest for an answer. The audience has access to 107 minutes of audio-visual material presented artfully and pointedly by Jarecki. We can’t see the case files or the raw interview footage. And Arnold Friedman’s silence – his downcast reticence to discuss the case in home-movie footage and his death in 1996, before the documentary was made – creates a gaping hole at the center of Capturing the Friedmans, at least if your primary interest is finding out whether Arnold and Jesse did it.

The movie is as much about the criminal-justice system, in spite of its declarations to the contrary, assuming guilt and meting out punishment accordingly. It’s about the troubling hysteria that follows accusations (no matter how baseless or incredible) of molestation, although it never really deals with sexual abuse as a problem. It’s about the frightful level of incompetence of and fear-mongering by television news, showing a handful of clips in which the Friedmans are breathlessly said to be accused of “sodomy and the sexual abuse of children,” as if anal or oral sex is a more serious and appalling crime than raping kids. It’s about the dissolution of an already fragile family. It’s about intimacy, the access offered by the omnipresence of recording devices in the Friedman household.

The movie is as much about the criminal-justice system, in spite of its declarations to the contrary, assuming guilt and meting out punishment accordingly. It’s about the troubling hysteria that follows accusations (no matter how baseless or incredible) of molestation, although it never really deals with sexual abuse as a problem. It’s about the frightful level of incompetence of and fear-mongering by television news, showing a handful of clips in which the Friedmans are breathlessly said to be accused of “sodomy and the sexual abuse of children,” as if anal or oral sex is a more serious and appalling crime than raping kids. It’s about the dissolution of an already fragile family. It’s about intimacy, the access offered by the omnipresence of recording devices in the Friedman household.

I’m most intrigued by a handful of details. The news photograph of Arnold and Jesse (I’m guessing at the courthouse) in which Arnold is averting his eyes and Jesse appears to smiling faintly at the camera – at a time when there’s an excellent chance he’s going to be locked away for the rest of his life. The way that eldest son David Friedman faces the television-news crews with underwear on his head. The fact that David kept a video diary and then gave it to Jarecki to use in the film. (He’s still wearing underwear, and only underwear, but at least it’s in the right place.) The way Jesse goofs around on-camera the day he reports to prison.

These are just a few of the moments when it became clear that the Friedman sons are performers; to me, the movie’s title has little to do with the police and everything to do with the amount of time, effort, money, and materials the family expended documenting itself on video and audio tape and film, from kick lines to arguments. About the only thing that wasn’t recorded – at least as far as we know – is the sexual abuse of children. And they’re so used to being in front of the camera, particularly the children, that they can’t help but be on all the time, playing to the lens.

These are just a few of the moments when it became clear that the Friedman sons are performers; to me, the movie’s title has little to do with the police and everything to do with the amount of time, effort, money, and materials the family expended documenting itself on video and audio tape and film, from kick lines to arguments. About the only thing that wasn’t recorded – at least as far as we know – is the sexual abuse of children. And they’re so used to being in front of the camera, particularly the children, that they can’t help but be on all the time, playing to the lens.

The Friedmans are the scourge of an entire community. They have nothing to say or offer that will improve anybody’s opinion of their family. Mostly, they just bitch about each other. But they talk to Jarecki. They need to perform, to be in front of the camera, no matter how bad it makes them look. (It’s no accident that David is a professional clown and magician.)

The movie has at least four layers of reality. At the bottom is “what happened” – the truth of the allegations of sexual abuse of children; we have no access to this. There is the unguarded material shot by the Friedmans, meant to remain private. Then there is the news footage of the Friedmans, intended for public consumption but still relatively candid. And on top there is the interview footage, in which the family and others talk to the camera with the understanding that it’s for mass consumption.

At least, that’s the way it should work. But I look at the photograph of Jesse and his father, and see David in front of the TV crew wearing underwear for a mask – most people would put their hands over their faces – and I think: These guys are never authentic, because they’re always on-camera. I don’t see any moments in Capturing the Friedmans that are unself-conscious. (Based on the prevalence of security cameras, home movies, and “reality” television, this seems to be a phenomenon affecting the entire culture.)

At least, that’s the way it should work. But I look at the photograph of Jesse and his father, and see David in front of the TV crew wearing underwear for a mask – most people would put their hands over their faces – and I think: These guys are never authentic, because they’re always on-camera. I don’t see any moments in Capturing the Friedmans that are unself-conscious. (Based on the prevalence of security cameras, home movies, and “reality” television, this seems to be a phenomenon affecting the entire culture.)

Then there’s Arnold, who almost seems to want to step out of the camera’s gaze when it’s trained on him. He’s the only person in the movie who appears to have a private life – that is to say, one that’s not recorded for posterity or the public. He created for himself a room that nobody was allowed to enter, and to the day he died in prison, he kept it locked.

(Related: Exonerating the Friedmans.)