A Postscript on Candyman (Or: The Trouble with Me)

A friend made me feel really stupid about my review of the new Candyman. He said I was “way wrong about a lot of fundamental things.” Pressed to explain, he wrote: “In a nutshell, that the movie was designed for people like you and me – for a prototypical white-person audience. I’d argue that that’s the very reason DaCosta doesn’t give us the scenes we expect, and why the only violence we see is directed toward white people. Black people don’t NEED to see more violence toward Blacks. It’s fine for it to be implied.”

We finally have a good point of comparison for the comic-book titans DC and Marvel: Wonder Woman and Captain Marvel. They were released less than two years apart; they both represented the first solo vehicle for a female superhero in their respective universes; they were both directed or co-directed by a woman; and they’re both origin stories that largely stand apart from ongoing narratives. In a narrow test of brand strength, they strongly support the idea that Marvel drinks DC’s milkshake.

We finally have a good point of comparison for the comic-book titans DC and Marvel: Wonder Woman and Captain Marvel. They were released less than two years apart; they both represented the first solo vehicle for a female superhero in their respective universes; they were both directed or co-directed by a woman; and they’re both origin stories that largely stand apart from ongoing narratives. In a narrow test of brand strength, they strongly support the idea that Marvel drinks DC’s milkshake. No television show loved language more than HBO’s Deadwood, but that statement comes with a caveat: It was not particularly quotable.

No television show loved language more than HBO’s Deadwood, but that statement comes with a caveat: It was not particularly quotable. Sometimes the success or failure of a movie, book, or television show hinges on a short passage. If that small part works, so does the whole; if the crucial bit comes up short, the entire enterprise falls apart. For me with the third season of creator/writer Nic Pizzolatto’s HBO series True Detective, the moment comes late in the finale when former cop Wayne Hays drives up to the house of a person he strongly suspects is Julie Purcell, who disappeared with her brother Will 35 years ago and has eluded him ever since.

Sometimes the success or failure of a movie, book, or television show hinges on a short passage. If that small part works, so does the whole; if the crucial bit comes up short, the entire enterprise falls apart. For me with the third season of creator/writer Nic Pizzolatto’s HBO series True Detective, the moment comes late in the finale when former cop Wayne Hays drives up to the house of a person he strongly suspects is Julie Purcell, who disappeared with her brother Will 35 years ago and has eluded him ever since. The question of what actually happened with Nora hangs over the finale of The Leftovers, but it is finally unknowable in any conclusive sense. Yet as much as the finale’s approach invites speculation, questions, and theories, it also tells us how to process it.

The question of what actually happened with Nora hangs over the finale of The Leftovers, but it is finally unknowable in any conclusive sense. Yet as much as the finale’s approach invites speculation, questions, and theories, it also tells us how to process it. Revisiting Netflix’s The Haunting of Hill House helped clarify the fundamental dissonance of the show – that running counter to its hopeful, tidy conclusion is something far messier in both its ghost and family stories. Yet the early episodes carve out room for readings that substantially darken the whole, undermining without negating the tone of its final minutes.

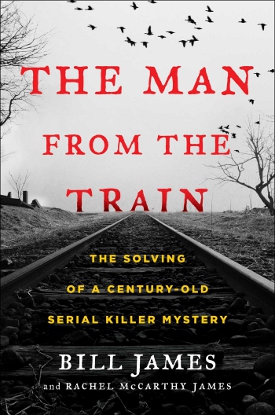

Revisiting Netflix’s The Haunting of Hill House helped clarify the fundamental dissonance of the show – that running counter to its hopeful, tidy conclusion is something far messier in both its ghost and family stories. Yet the early episodes carve out room for readings that substantially darken the whole, undermining without negating the tone of its final minutes. Bill James’ The Man from the Train is an ugly book, but for the most part you shouldn’t read that as a criticism. It’s ugly in three ways, and two of those were certainly unavoidable given the subject – the murders of more than 100 people in the early part of the 20th Century. But the third way could have been mitigated to at least some degree.

Bill James’ The Man from the Train is an ugly book, but for the most part you shouldn’t read that as a criticism. It’s ugly in three ways, and two of those were certainly unavoidable given the subject – the murders of more than 100 people in the early part of the 20th Century. But the third way could have been mitigated to at least some degree. Adapted from Gillian Flynn’s debut novel, HBO’s Sharp Objects is a whole bunch of greatness that, finally, amounts to not much of anything.

Adapted from Gillian Flynn’s debut novel, HBO’s Sharp Objects is a whole bunch of greatness that, finally, amounts to not much of anything.