(The Spoiler’s Creed is in full effect.)

No Country for Old Men

My first thought after watching Joel and Ethan Coen’s No Country for Old Men – amid groans from others in the theater – was that I understood why some people hate it.

My first thought after watching Joel and Ethan Coen’s No Country for Old Men – amid groans from others in the theater – was that I understood why some people hate it.

This was prompted by something I’d read earlier that day, an item from Roger Ebert’s Movie Answer Man column:

“I went to see No Country for Old Men with a group of my friends. I was absolutely fascinated and riveted by the film and think it is the best film I have seen thus far this year. My very good friend, who also happens to be a very smart guy, thought the film was terrible. I was shocked. Should I debate the merits of the film with him? Is it even worth debating such a wonderful film when the person you are debating with has no appreciation for it, and does it pose a risk to the friendship?”

It’s a fair and fascinating question, but Ebert’s reply was unfortunately glib:

“As Louis Armstrong instructs us, ‘There are some folks that, if they don’t know, you can’t tell ’em.'”

I might accept that dismissive response if he were talking about Transformers or some tony, repressed period romance; we all have things that we just don’t like, no matter how well they’re done.

But No Country for Old Men subverts audience expectations at just about every turn, and despite its considerable pleasures and a straightforward chase-the-drug-money plot, it’s a willfully difficult film. In that context, why wouldn’t you want to argue about it? It’s the rare movie that’s open enough to foster malleable opinion; thoughtful people who dislike it initially can be won over if spurred to look at it differently.

Five days later, I’m still not sure how I feel about it. I enjoyed the experience but was baffled by the conclusion. We’ve made our peace – a little – but I’m still uncertain where I’ll end up on it.

The movie is framed by Sheriff Ed Tom Bell (Tommy Lee Jones), who begins it with a voiceover and ends it with the recitation of a dream. I’d be lying if I said I followed what he said; in both cases, I was mesmerized by the rhythm and tone of the actor’s readings.

The movie is framed by Sheriff Ed Tom Bell (Tommy Lee Jones), who begins it with a voiceover and ends it with the recitation of a dream. I’d be lying if I said I followed what he said; in both cases, I was mesmerized by the rhythm and tone of the actor’s readings.

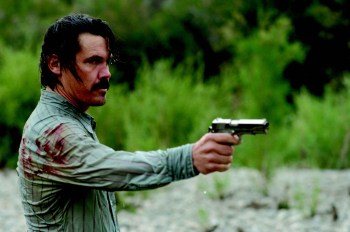

Bell is almost tangential to the core story of No Country, which concerns Llewelyn Moss (Josh Brolin), a trailer-park resident who finds serious money at the scene of a drug deal gone bad, and Anton Chigurh (Javier Bardem), a mercenary on the trail of the cash. Bell is largely a bystander, a witness to a lot of messes but only briefly in the presence of either of the other main characters.

Llewelyn is killed well into the movie – but long before it’s over. I imagine that the shock that attends his death is kin to that generated by Psycho when it first came out.

And the remainder of No Country offers no conventional closure. The audience anticipates a showdown, a battle of wits, between Bell and Chigurh, and the Coens set it up, but they instead give us two anticlimactic scenes that have no obvious connection to what preceded them.

Those are just the big challenges to liking as a whole No Country for Old Men – faithful, says Bride of Culture Snob, to the source novel by Cormac McCarthy.

Beyond that, I wouldn’t begrudge any viewer a moment or two of confusion about whether that body does indeed belong to Llewelyn. And I certainly understand how people might believe that Chigurh let Llewelyn’s wife live; the evidence to the contrary is delivered by the Coens with a gorgeously subtle gesture that’s easy to miss. The audience doesn’t see Chigurh shoot the woman. It doesn’t hear the gunfire from a distance. It sees him exit a house and check the bottoms of his shoes.

Other touches will go unnoticed by most folks but will still have an unsettling effect: the dearth of music, for instance, and the way a key bit of deduction by Bell is delivered through a story and without the typical a-ha shot.

And then there’s Chigurh, a great villain in part because he’s so difficult to peg. It’s not merely that Chigurh’s undiluted evil and that fabulously awful helmet of hair make it impossible to empathize with him. Moral considerations aside, it’s doubtful that he’s even a human being. He is almost supernaturally resourceful, and unless you read a lot into a tossed-off comment about him being a ghost (I’m receptive to the idea), the mystery of his methods will open up plot holes as frequently as his weapons spill blood.

And then there’s Chigurh, a great villain in part because he’s so difficult to peg. It’s not merely that Chigurh’s undiluted evil and that fabulously awful helmet of hair make it impossible to empathize with him. Moral considerations aside, it’s doubtful that he’s even a human being. He is almost supernaturally resourceful, and unless you read a lot into a tossed-off comment about him being a ghost (I’m receptive to the idea), the mystery of his methods will open up plot holes as frequently as his weapons spill blood.

The case with the money has a transponder, and Chigurh has a receiver, but that doesn’t explain the man’s startlingly accurate homing instincts. If he feels some need to kill you – or, if you’re lucky, to tie your fate to the flip of a coin – he’ll find you, and the Coens give no indication that he’s engaging any investigative skills.

The audience learns all it ever will about Chigurh at the outset; when we first meet him, he kills a deputy while handcuffed. He then puts a clean hole through a man’s skull with an air gun.

It’s the blank spaces – what we don’t know about him – that intrigue and frustrate the audience. Who is he? Who does the ’do? What could have created this monster?

Even after spending time with Llewelyn, we don’t have a firm grasp of him, either, but we know he has more of a heart than Chigurh. Feeling guilty about leaving someone to die, he returns to the place where he found the drug money to give water to a wounded man. While belatedly compassionate, this decision can only lead to bad things. And it does.

On further consideration, though, it probably prolongs his and his wife’s lives. He gets a glimpse of what he’s up against, and if he didn’t, he would be an easier target.

He ends up a worthy foe, a harder kill for Chigurh than the “professionals” he dispatches without effort. Llewelyn is tougher because he’s unpredictable, and we root for him as the everyman against a seemingly unstoppable opponent.

The audience is invested, then, not in the characters but in the contest. While the Coens’ Fargo was populated with colorful, detailed idiots and one sensible police chief, the three major players in No Country for Old Men are sharp if not wise.

There’s one other comparison with the brothers’ 1996 film that’s instructive. Humor streaks No Country for Old Men, but unlike in Fargo, it’s not the primary purpose, and it’s not of the mocking, superior variety.

All of this contributes to a movie that – no matter your final judgment – is easy to enjoy. There’s also the Spaniard Bardem, playing a man whose first tongue is clearly not English; his pronunciations and deliveries are filled with odd pauses and sounds not native to the language, giving his mostly senseless dialogue a striking weight.

That’s contrasted with the casual vernacular poetry of Jones, which is contrasted with a nearly invisible performance by Brolin (and I mean that as a compliment). To those turns you can add Woody Harrelson, playing a mercenary out to get the mercenary who’s confident and competent without being particularly bright, or

who at least projects that he’s not very bright. The actor has a glorified cameo, but he creates a character through a drawn-out deliberateness; he appears to be thinking about thinking about something important.

But does all this constitute a coherent film? Is it meaningful? Or is it merely a collection of disparate gratifications?

At The House Next Door, Matt Zoller Seitz argues against the prevalent moral and political readings, saying that the movie is about a failure to recognize inevitable cycles:

“No Country’s message, such as it is (the Coens aren’t message-y directors), is not about Where We Are Now. It’s simpler and more encompassing, less reminiscent of reportage or the editorial page than the admonitions of a philosopher or court jester: Get over yourselves, Americans, and everyone else, too. Look beyond yourselves and the time you live in. What is happening to the United States and the world – and every individual – is a variant of a dynamic that recurs throughout personal and political history, as predictable as the end of one year and the start of the next. What you got ain’t nothing new.”

I think he’s ascribing to No Country the lesson that the new always obliterates the old, a function of the old’s twin blind spots of comfort and nostalgia:

“Bell’s belief that he lives in a time of fixed realities and diminished potential is indicative of the mentality that makes a dominant culture vulnerable to aggressive revisionists. To the people Bell hopes to stop, the future is a wide-open road. The status quo’s defenders are speed bumps.”

That seems a stretch. It has to work too hard to contain the movie, particularly the car accident of the penultimate scene. The strain of the explication shows with a closing consideration of Chigurh:

“[H]e enters the story in handcuffs and leaves it bloody and broken-boned, trudging through the suburbs on foot.”

This is a lovely sentence, but it doesn’t really fit the interpretation, and its defeatist implications contradict what we know about the character: His captivity, and his injuries, are short-lived.

I wonder if No Country for Old Men might be simpler still: We’re all in over our heads.

I wonder if No Country for Old Men might be simpler still: We’re all in over our heads.

That’s obvious with Llewelyn as soon as he takes the money. It’s apparent with Bell when we recognize the ruthlessness of Chigurh. It’s apparent to Bell when he figures out that he’s no longer cut out for police work, and that he’s not yet suited for retirement.

And here’s where that puzzling traffic accident comes into play. Chigurh has to this point appeared invulnerable; even when Llewelyn shoots him in the leg – a nearly miraculous feat, all things considered – he quickly acquires the means to heal himself. And because he’s a more skilled hunter than anybody else, it seems unlikely that somebody could purposely do worse to him.

The car wreck hints at Chigurh’s weakness and mortality, even though it doesn’t kill him. He survives by chance, not because of some extraordinary aptitude. (We have no evidence of Chigurh’s superior defensive driving.)

You can be the baddest-ass killer on the whole planet – smart, wily, brutal, capricious, without conscience, and with an unerring nose for the requisite trouble. And you can be oh so careful, tying up loose ends and obeying stoplights. (The Coens emphasize that Chigurh is mindful of traffic signals.) But you can’t stop some asshole from running a red light and plowing into your car. Dumb luck can kill you, and there’s nothing you can do to prepare for it.

All this casting about for meaning might seem pointless with a movie this slippery, but the search for substance and import in No Country is warranted. The Coen brothers might not be “message-y,” but Fargo was neatly, accurately reduced to Marge Gunderson’s rebuke: “And for what? For a little bit of money. There’s more to life than a little money, you know.”

And while some movies don’t lend themselves to moral or cultural interpretation – they aren’t about anything significant – No Country for Old Men demands, with its curious denouement, a framework within which to process and understand it.

If it wrapped up its plot shortly after the death of Llewelyn, it could have been purely suspenseful. Instead, the Coen brothers are begging you to reconsider what you’ve watched.

I did, and I’m still not sure what I saw.

I saw this movie two weeks ago and I think the key to the movie is to see it through the eyes of Ed Tom Bell who is both the storyteller and sage. The fact that he has no answer to Chigurgh or the madness that the men in the story do sums up the complexity of the film. I’ve loved the Coens since watching Raising Arizona as a teen and I’m amazed how they can still surprise audiences twenty years later, a feat that has to be more difficult each time out.

This is one of those films where I can totally love it and yet totally see where the detractors are coming from. The discussion over at Jim Emerson’s Scanners site has been very interesting, and many of the negative reactions to the film seem to hinge on small differences of interpretation in the details.

The final act of this film pretty much demands careful thought about the meaning of it all, and I think the film’s crux is the scene where Bell goes to visit the older retired sheriff, who tells him a story about a violent incident in the Old West. It’s a moment of awakening for Bell, who throughout the film had felt overwhelmed by what he believed was a distinctly modern evil, an outgrowth of changing times. This story drives home that there will always be evil and violent people, and it will always be a challenge for decent people to survive in a cold world. Bell pretty much fails to live up to the challenge of confronting evil, essentially resigning himself to Chigurh’s rampage. But the film itself stresses the importance of this challenge.

“Dumb luck can kill you, and there’s nothing you can do to prepare for it.”

I like the way you’ve underlined this theme, and I think you’re right. It’s really emphasized by the coin tossing scenes–even people who are “intentionally” killed are killed out of a kind of dumb luck.

At the same time, I’m not sure if the dumb luck theme is the same thing as “we’re all in over our heads.” That seems to suggest a way out–don’t get in over your head, leave the money and run. But the dumb luck theme in this film seems more fatalistic: death will get you, no matter how lucky or skillful or careful you are, and everyone’s luck, even the almost supernaturally effective supervillain’s, will run out.

“There will always be evil and violent people, and it will always be a challenge for decent people to survive in a cold world. Bell pretty much fails to live up to the challenge of confronting evil.”

I agree that there is a suggestion of the inevitability of evil and violence, but I don’t get the impression that the film endorses taking up that challenge. Indeed, if we take its fatalism about the inevitability of evil seriously, what’s the point of challenging it? There’s a degree of defeatism in the film–as if combatting evil only makes it worse, and we’re better off leaving well enough alone. I don’t buy that myself, but it felt like the film did. The issue of chance seems to push in the same direction. If it’s all a coin toss in the end, why try to influence the results?

Chris: You’re correct. Given the framing, Bell is either the key, or it’s a bad movie.

Ed: Your reading fits well with The House Next Door’s. I’ll need to see the movie again before I can reach any firm resolution on the movie.

CK: You got me. I could try to tie those two strands together – luck and being in over one’s head – but I agree with you that they’re distinct. I hadn’t even considered the coin tosses in the context of the car accident, and yes, I’m that stupid. I’m not sure how much we should fault Bell for not confronting Anton; he did try.

This is a movie I’ll surely write about again, and the discussion surrounding it will undoubtedly inform where I end up on it.

No Country for Old Men is about morality. It’s about the difference between having and not having one, and how a person can have a morality that has a much different content than the one most people accept. In the book by Cormac McCarthy, Sheriff Bell can’t understand the young killer in the Huntsville prison who kills a fourteen-year-old girl just because he wants to, not out of self-interest. He acknowledges that he is going to hell for what he has done, but says he would do it again if they let him out.

The young killer is not like the cattle rustlers that Sheriff Bell’s grandfather had to deal with, for they stole out of self-interest. Chigurh is like neither the young man in the Huntsville prison nor the cattle rustlers. That is because he acts from principle, not self-interest, and so is not like the young man (who acts from neither principle nor self-interest), nor like the cattle rustlers (who do not act from principle but do act from self-interest). In the book, Carson Wells, the hitman hired to kill Chigurh, says of Chigurh, “He’s a peculiar man. You could even say that he has principles. Principles that transcend money or drugs or anything like that.” Chigurh tells Llewelyn’s wife that he has to kill her because he had given his word to Llewelyn that if he did not tell him where the money was he would kill both him and his wife. Chigurh is a man of his word! Further, Chigurh kills Wells’ boss with birdshot to avoid breaking the window behind him that would cause glass to rain down on the innocent people on the street below. Chigurh has a morality, but it is not like ours, though somewhat like Sheriff Bell’s. Unfortunately, the Coen brothers left out a passage from the book that contains a conversation that Sheriff Bell has with his Uncle Ellis in which he says how he feels guilty for leaving his men behind in a wartime situation where they were doomed to die. He thinks that because he gave an oath to look after them he should have stayed with them even though that would have cost him his life. Both Chigurh and Sheriff Bell are men of their word, though we think it makes a big moral difference if you promise to kill an innocent person or to look after your men in wartime. Like the John Travolta and Samuel Jackson characters in Pulp Fiction, Chigurh has a morality, unlike both the young man in the Huntsville prison and the cattle rustlers. However, none of these hitmen has a morality whose content is like the content of our morality or Sheriff Bell’s. We might disagree with Sheriff Bell and think that he should have escaped when any attempt to save his men was futile, but we at least understand how he could be committed to staying with his men at all costs. We cannot understand how it could be morally permissible for Chigurh to keep his promise to kill Llewelyn’s wife. This is No Country for Old Men because men (and women) with old values cannot make sense out of someone killing for that reason, or killing someone just because he wants to and not out of self-interest.